Cinder & The Crown

– Part I

Story Written By

Queen Aveline Beaumont,

Crown Steward Cinder Dubois, Duchess Claudine Delisle,

& Madame Esmée Étoile

Told Through the Voices Of

Queen Aveline Beaumont

& Crown Steward Cinder Dubois

Visuals & Imagery Conjured By

Liora Marivelle, Céleste Rousselle,

Théa Lavellan, Éline Vervain,

Maëlle Étoilemont, & Scott Bryant

Spellwork & Whispered Magic By

Madame Esmée Étoile

With steadfast loyalty, our story is shared by

Scott Bryant, at the royal request of Queen Aveline Beaumont, Crown Steward Cinder Dubois, Duchess Claudine Delisle,

& Madame Esmée Étoile

I believed my story would be written for me—a crown pressed to my head, my steps measured by expectations, my words never truly my own. But I learned, sometimes through fire, that the world is not balanced by silence.”

— Queen Aveline Beaumont

“They called me Cinder because I lived among the ashes. But even from the soot, I learned to see sparks.”

— Crown Steward Cinder Dubois

Part 1: The Beginning

The Whispers

The valley breathes, though no one else seems to hear it but me, Cinder Dubois. The mistral—Provence’s fierce southern wind—threads through the branches, carrying whispers soft and lilting, like the chansons I heard in the marché. The rivers hum like ancient melodies, their rhythm alive with stories I cannot yet unravel. The air carries hints of lavender and wild thyme, as though the land itself is weaving its song into my senses.

My mother once told me the land speaks to those who listen—not in words, but in rhythms.

Balance, my little Cinder, she’d say, is more than a thing to see. It’s something you feel, like the rise and fall of your own breath.

I didn’t understand her then. But now, when the breeze twists through the hills, I sense its quiet questions—questions I can’t yet answer, though I feel them waiting in the soil beneath my feet.

Stepmother & Stepsisters

“Cinder, fetch more firewood,” Sabine snaps, not even looking up from the embroidery she mangles with her clumsy hands. “The salon is cold.”

“Cinder, fetch the butter,” Aimée commands, her tone syrupy but no less biting. “And be quick about it. My tartine is turning hard.”

Cinder.

The name isn’t mine, but it’s been pressed into me so deeply it feels like a scar. It clings to me like the ash I scrub from the hearth, smudging my skin until I can’t tell where it ends and I begin. The first time they called me that, I felt the sting of it, like hot embers against bare skin. Now, I hear it and feel nothing—nothing but the hollow ache of forgetting who I was before the soot.

But sometimes, I wonder—if I scraped away the ash, if I peeled off the name they’ve given me—what would be left? Would I find something worth holding on to, or would I be nothing but the fragments they’ve left behind? My mother’s journal tells stories of stewards, of people who listened to the land and found their strength in its whispers. Did they ever feel like this—small, broken, unworthy?

Today, I don’t answer when they call for me. Not because I’ve grown used to the name, but because it no longer defines me. I leave the broom behind and step into the forest. Letting the murmurs lead the way, I step into the feeling that I am no longer running away, but rather running towards something.

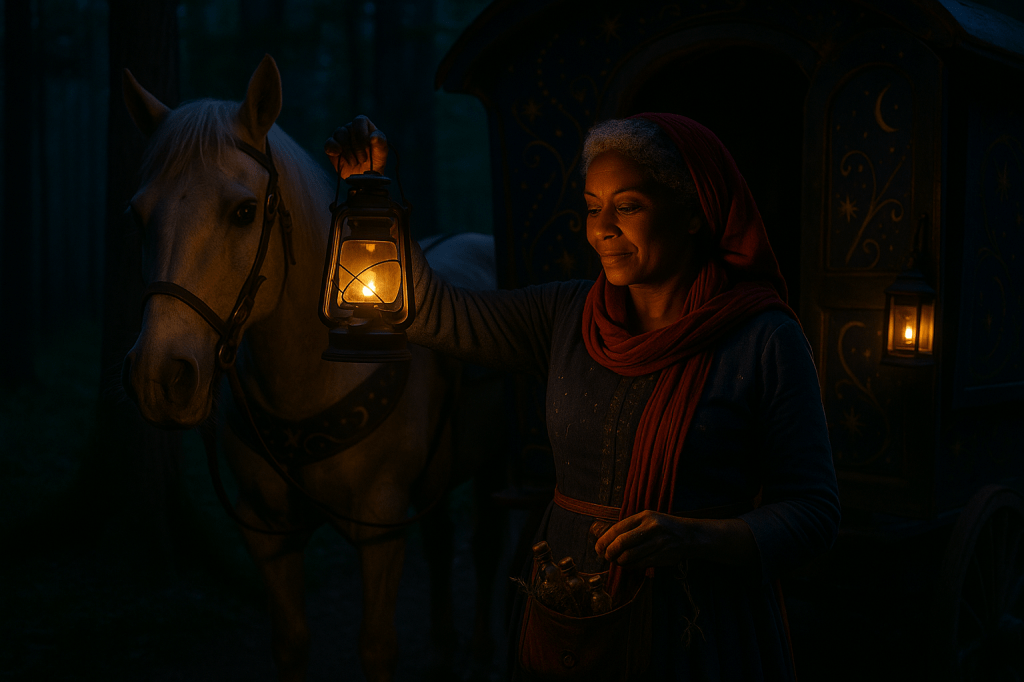

Esmée Arrives

Madame Esmée Étoile’s caravan arrived early in the morning before dawn, its familiar rattle echoing through the valley. She disappeared into the woods before anyone could stop her, the red scarf trailing behind her like a flicker of flame. Her presence always feels deliberate, as though she’s weaving herself into the balance of the land. Some villagers muttered that she’s more spirit than human, her steps as light as the wind threading through the branches.

My mother’s journal mentions her in ways that now seem impossible to ignore.

Esmée, she wrote once, is not just a healer. She listens to the whispers better than anyone, as though she’s part of the land itself. Perhaps she always has been. She is both a guide and a guardian, a tether between us and the balance we often fail to see.

I used to think his words were just fanciful musings. Now, I wonder if they were warnings I failed to understand.

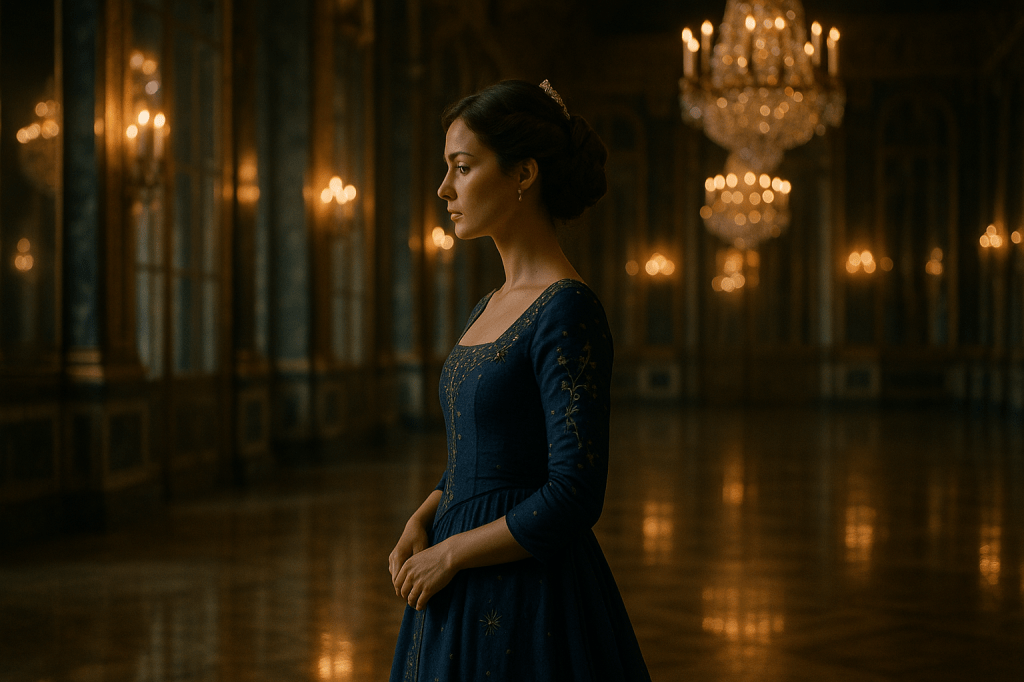

A Gilded Cage

The Hall of Mirrors—La Galerie des Glaces—is a hollow kind of beautiful.

Its polished Carrara marble floors gleam like still water, reflecting the intricate gold leaf filigree that coils along the walls and the cascading tiers of crystal chandeliers. The scent of orange blossoms lingers in the air, faint but deliberate, a subtle signal of the court’s prosperity carefully arranged by the attendants to dazzle the southern delegates from the Provinces Occitanes.

When the hall is filled with people—spinning, laughing, scheming—it hums with life, the air thick with perfume.

But when it’s empty, as it is now, the silence feels like it’s watching me, Princess Aveline Beaumont.

The grandeur is too perfect, too precise.

It doesn’t feel like it belongs to me.

It never has.

In a week’s time, this hall will host the grand ball my mother, Queen Geneviève Beaumont, has planned for months.

She says it’s meant to honor me as the kingdom’s heir, but I know the truth.

It’s not about honor. It’s about marriage.

I glance at my faint reflection in the marble floors, the crown of duty already weighing heavier on my shoulders than any gold or gemstone. A steward must balance the needs of the land; a queen must balance the expectations of the court. But what if I cannot be both?

“Everyone will be watching,” she said last night over dinner, her tone clipped, her gaze sharper than her diamond earrings.

“You must dazzle them, Princess Aveline. A crown rests heavier on a woman’s head.”

As if I don’t already feel its weight pressing down.

I pace the length of the hall, my footsteps catching on the marble. My fingers skim the banquet table, cold beneath my touch, its surface polished to perfection. My reflection stares back at me, but it’s not a comforting sight.

All I see is the performance I’ll have to give, the smiles and curtsies, the quiet endurance that seems to come so easily to my mother.

It’s harder for me.

I’ve never wanted to be a doll, no matter how pretty the dress.

For a heartbeat, I catch my reflection in the glass of the banquet table—and in the shimmer, I think I see another figure. Not my own, but a trick of the light… or a girl I’ve yet to meet.

“Aveline. Your Highness.”

Claudine Delisle’s voice draws me from my thoughts. Both my closest advisor and lady-in-waiting stands in the doorway, her expression unreadable. She doesn’t ask if I’m alright—she knows better than to waste words on questions like that. Instead, she steps closer, her voice low and calm.

“The diplomats from the southern provinces have arrived. Lord Thibault, too.”

“Of course,” I say, as though it doesn’t matter, though the knot in my stomach tightens. Diplomats mean more masks to wear, more measured words and careful smiles. But somewhere beneath the dread, there’s a flicker of something else.

Hope. That maybe, for once, someone will see me, not the polished mask I wear.

Esmée’s Wisdom

The forest smells like damp earth and pine, a sharp, clean scent that makes me feel lighter with every step. It’s quieter here—no sharp voices, no clatter of wooden spoons against pots, just the crunch of leaves beneath my boots. However, there is also another thing, the mood. A soft hum, like a low note vibrating beneath the skin of the world. I only ever feel it when Esmée is near.

She waits in the clearing, her red scarf vivid against the green, her dark eyes catching the sunlight like river stones. Her smile is sharp and warm at once, the kind of smile that says she knows far more than she’ll ever tell. There’s something about her, something otherworldly. I’ve always thought she belongs more to the forest than to the road.

“Bonjour, ma chérie.” Her voice lilts like birdsong. Hello, my darling. “You’ve grown.” She glances toward the trees as though the forest itself had whispered my secrets to her. “And still sneaking away?” Her smile is sharper this time, as though she knows the path I’m on before I do.

“Only when it’s important,” I reply, though we both know that isn’t true.

“Bien.” She straightens, brushing her hands against her skirts. Good. “The world is better for it.”

Esmée has always seen me—not the servant, not the ash-streaked girl Madame Violette scolds, but me. That’s why I come here, no matter the risk. She doesn’t care about the rules of the estate or the titles that weigh other people down. To her, I am something more.

Her sharp, knowing gaze often carries the weight of unspoken truths, and I’ve begun to suspect she knows more about the whispers than she’s ever shared. Perhaps she doesn’t just hear them—perhaps they answer her.

“Your mother stood here too, once. The whispers never stopped missing her.”

She turned to the wind.

“They’ve waited a long time for you, child of rhythm. The whispers guide you because they see you as part of the balance,” she tells me, her voice soft yet firm. “Do not fear that calling, Cinder. It is yours by right.”

“There’s a rhythm in you, ma chérie,” she told me once. “And rhythms can change a world.” At the time, I didn’t understand. Now, I wonder if she meant the balance.

Esmée’s fingers move with practiced ease, sorting through her basket of jars and herbs. The sunlight filters through the trees, casting shards of rainbow light.

“Tu ne viens pas pour rien,” she says, her tone deliberate. “You don’t come for nothing”. She watches me closely, her sharp smile deepening. “There’s always a reason, ma petite.”

I roll the rosemary between my fingers, the scent sharp, familiar—and comforting in ways I don’t fully understand.

“It’s getting harder,” I admit. “To leave, to come here. Madame watches everything.”

“Bien sûr.” She nods knowingly. Of course. “The cruel always fear what they don’t understand.” Her voice softens as she tucks a stray strand of her dark hair behind her ear. “Mais n’oublie pas, ma petite. Don’t forget, my little one. Don’t let her see you falter. If you do, she’ll think she’s won.”

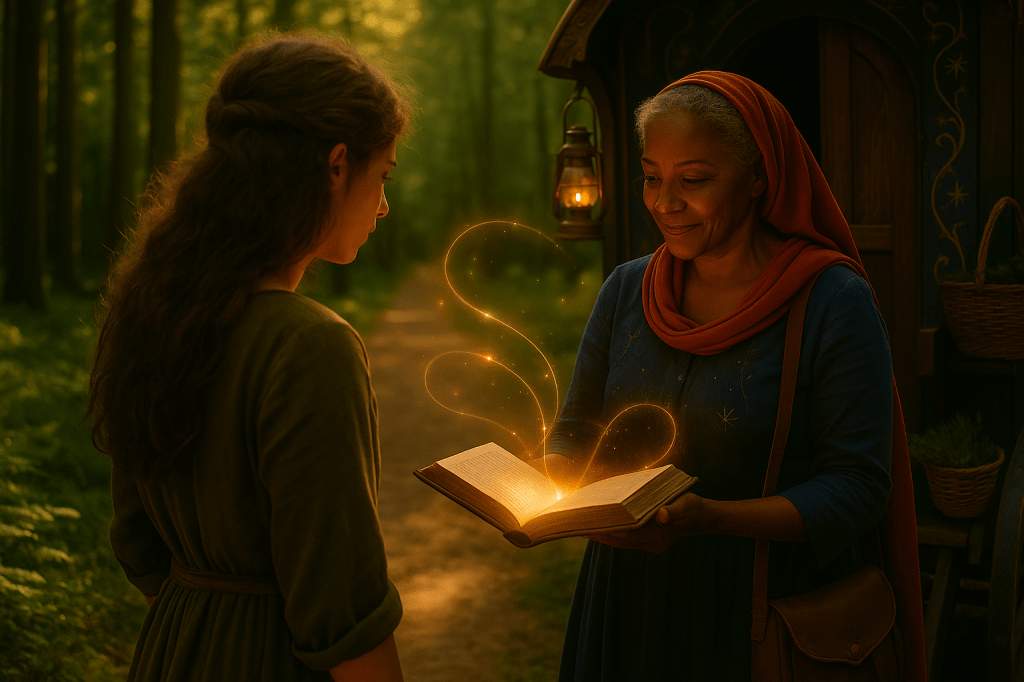

I want to ask her how she knows these things, how she sees through people as easily as she sees through me. But before I can, she pulls a book from the folds of her basket and places it in my hands.

She drew the book from the folds of her wagon with deliberate care, as if lifting something sacred from a cradle. The cracked leather creaked softly in her hands, worn smooth by time and use. As Esmée passed it to me, the scent of dried lavender rose gently between us—familiar, grounding, like something half-remembered from childhood.

“Tu sauras quoi en faire,” she said, her voice low and sure. You’ll know what to do with it.

I hesitated. The book felt warm in my hands. Alive, somehow. I could feel a hush spreading through the trees around us, like the valley itself had leaned in to listen.

“I don’t know magic,” I whispered, almost apologetically.

Esmée smiled. That knowing, impossibly kind smile of hers. “Pas encore,” she said. Not yet.

Her words settled over me like the warmth of a hearth fire on a winter morning. And then—subtle at first—I felt them: the whispers. They curled through the air like tendrils of smoke, brushing against my skin, humming in rhythm with something inside me I had never quite heard before.

“Take it,” she said, not as a request but as a truth. “You’ll need it soon.”

And in that moment, I believed her.

Not because of the glow beginning to stir from the book’s spine, or the way the light bent gently around Esmée’s red scarf like a halo. I believed her because the valley did. Because the trees did. Because something deep within me stirred—and answered.

The book feels heavy in my hands, though it isn’t large. Its leather cover is worn and cracked, its pages edged in gold that glints in the sunlight. When I open it, the scent of lavender and something darker—sage, maybe—drifts out. The pages are filled with elegant, looping script and intricate drawings of plants, stars, and something that looks almost like music notes.

“What is it?” I whisper.

Her hand lingers on the book, her gaze distant for a moment.

“This is not just a guide, ma petite. It is a part of the balance itself—a record of its rhythms, its secrets. It will not yield its truths all at once. You must be patient. You must listen.”

I feel the weight of her words settle into me, as though they are not hers alone but a truth that flows from the land itself. Esmée’s presence feels different now—less like a mere healer and more like the whispers themselves made flesh.

The Gift Between Winds

Cinder

The wind had stilled.

Esmée had vanished again, but something remained. Not in the clearing—in me. I clutched the grimoire to my chest, grounding myself. But something else stirred in my satchel. I reached inside and found it.

A pendant.

Not stone.

Not crude.

A heart-shaped locket, warm and cool all at once, its surface catching the last light of dusk.

Polished, but not gaudy—just… honest.

Simple.

Real.

I didn’t know why I’d carried it all this time. It had belonged to my mother once, I thought.

Or maybe it had never belonged to anyone at all.

Just waited.

I turned it over. The metal held a quiet warmth, like it remembered being held.

“I saw her,” I whispered. “In a dream. A hall of mirrors… She was watching herself, but looking for something else.”

It pulsed faintly. Not with magic—something older. Intention.

“She doesn’t know me,” I said. “But I think… she hears what I do.”

From the shadows, Esmée reappeared.

“As do you.”

She stepped forward, palm open.

“Let me carry it. She’ll wear it, even if she does not yet know why.”

I imagine her fingers brushing the clasp, unaware it once rested in mine. The thought is too warm for the cool forest air.

I pressed it into her hand.

“She won’t know it’s from me.”

“No,” Esmée said gently. “But she’ll feel it, all the same.”

And then, she was gone again.

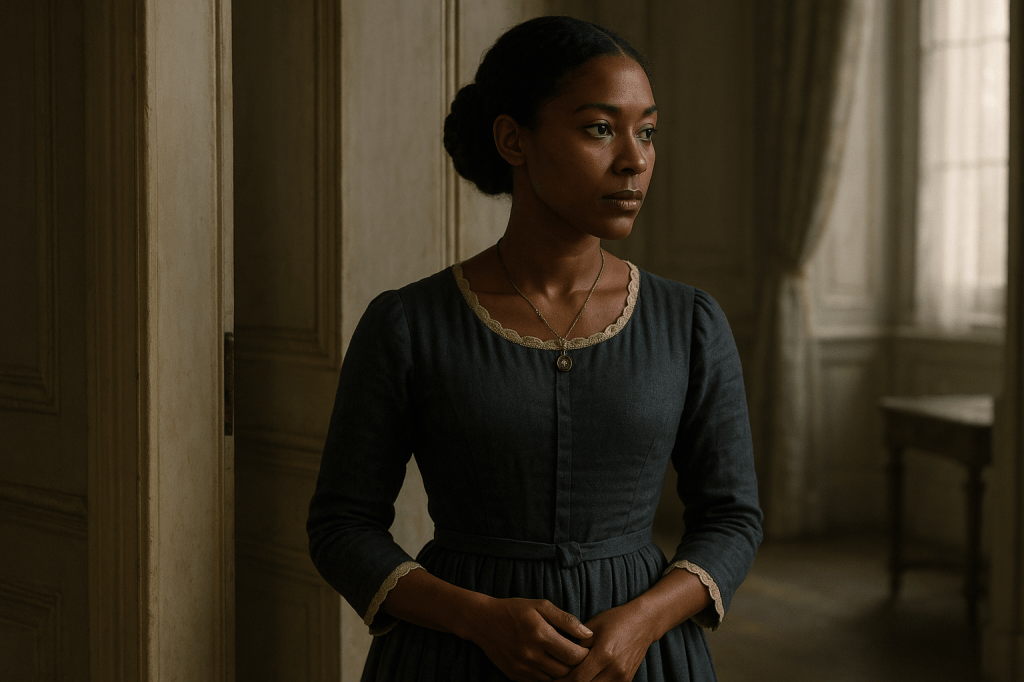

The Weight of Appearances

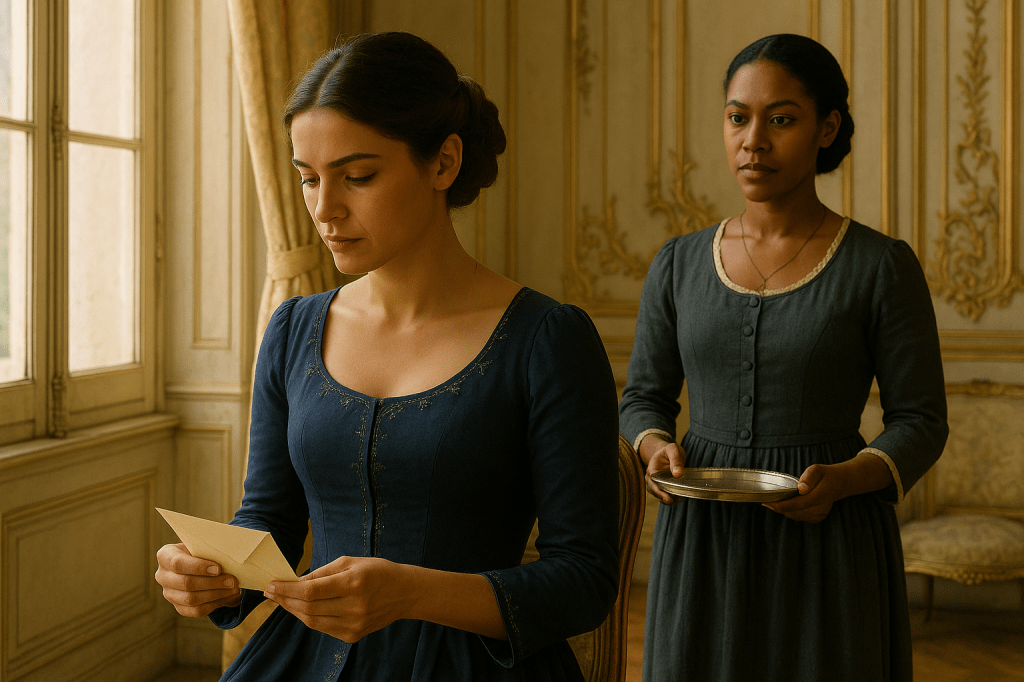

The afternoon light streams through the tall windows of my sitting room, painting golden patterns on the parquet floor. Claudine stands by the vanity, holding up two gowns—one in deep blue satin and the other a pale gold that glimmers like sunlight.

“Which one do you prefer, Your Highness?” she asks, her voice careful, as though the wrong answer might shatter the fragile peace of the day.

I stare at the gowns but see only the expectations draped over them. “Does it matter?” I say finally. “It’s all the same to the court.”

Claudine sets the gowns down and steps closer. Her dark eyes meet mine, and for a moment, the air feels heavier, quieter.

“It matters,” she says. “Not to them, but to you.”

Her words catch me off guard, though I try not to show it. Claudine always knows when I’m slipping, when the weight of everything feels too much. She never says it outright—she’s far too clever for that—but her reminders are always there, steady and unshakable.

“The blue,” I say, more to please her than myself. “It’s less expected.”

She smiles faintly, folding the gold gown with practiced precision.

“Less expected is always better, don’t you think?”

The Grimoire’s Secrets

The book is heavier than it looks, and the air feels thicker as I carry it back through the forest. By the time I reach the crumbling estate, my arms ache, and my heart thuds with the fear of being caught.

Madame Violette doesn’t ask questions when she finds something she doesn’t like—she punishes first and assumes guilt later.

I tuck the book beneath the loose floorboard under my cot, where my mother’s old journal still sits. A sprig of dried lavender rests beside the journal—an offering my mother once said kept malevolent spirits away. He always believed lavender carried the wisdom of the forest.

As the house falls quiet, I light a candle stub and let its faint glow spill over the pages. Only then do I dare open the book again.

The pages feel alive, humming beneath my fingertips. They’re filled with drawings—plants I recognize, like lavender and sage, but others I’ve never seen. Stars arranged in patterns that make my head spin if I stare too long. At the center of one page, there’s a symbol that makes my breath hitch: a circle surrounded by delicate lines, almost like a flower, with sharp points that remind me of the thorns I used to pull from my mother’s rose bushes.

The journal’s pages fluttered open to a passage half-faded by rain.

“The land listens best when you bleed and believe at once.”

I touched the ink as if it were skin.

The symbol seems familiar, as though plucked from the pages of an old Provençal grimoire. My mother once told me about protective sigils carved into ancient stones, the markings meant to tether a balance between earth and sky. I trace the lines, and for a moment, I swear I feel something move beneath my fingers—a warmth, faint and fleeting, like sunlight breaking through the clouds.

The air thickens, wrapping around me like a cloak. And then I feel it: a voice, not in my ears but in my chest, vibrating against my ribs as though my body itself were the drum for its rhythm.

“Find the crown.”

I jerk my hand away, slamming the book shut. The voice is gone, but the words linger, threading themselves into the whispers I’ve heard all my life. For the first time, I wonder if they’ve been leading me somewhere all along.

A Locket Arrives

Aveline

It appeared with no name.

No note.

Just a small velvet pouch, left neatly on the sill of my chamber, its drawstrings still warm to the touch.

As if someone had only just been there.

Inside: a heart-shaped locket, metal, understated, elegant without opulence.

Not courtly.

Not adorned with jewels.

Just deliberate.

I clasped it around my neck that night.

When I wore it, something inside me calmed. As though the locket carried not a picture, but a presence—something seen without being spoken.

“Where did you come from?” I once whispered aloud.

The locket offered no answer. But I wore it anyway.

And when I did… I felt closer to myself.

The Pressure of the Court

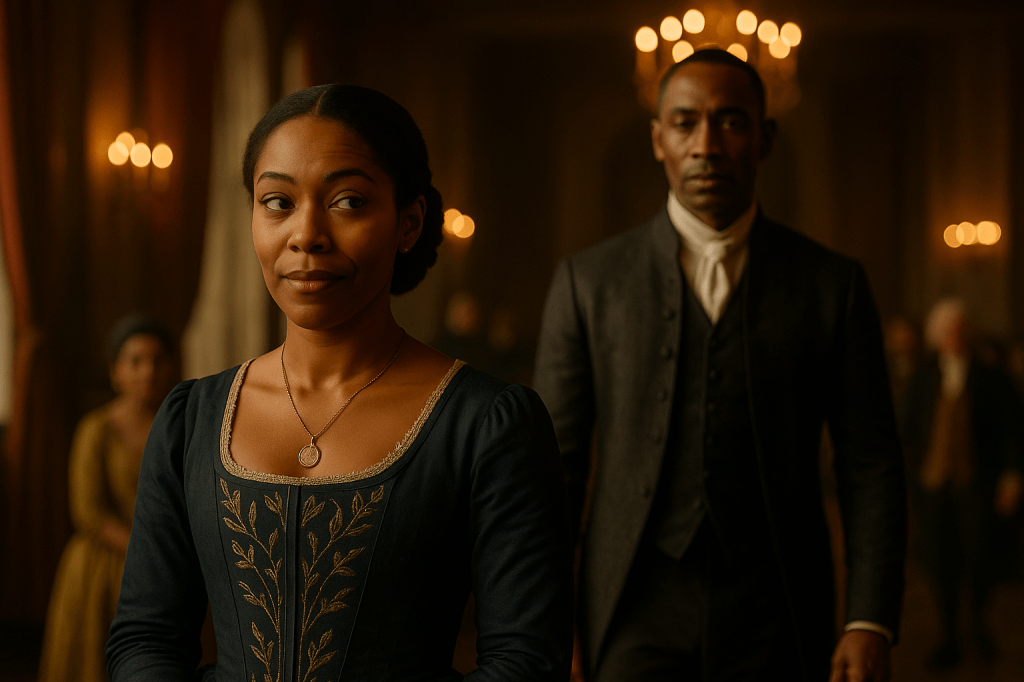

The great hall buzzes with voices, the low hum of conversation punctuated by the occasional burst of laughter. Courtiers mill about in clusters, their powdered wigs and embroidered jackets catching the light from the chandeliers.

They speak of trade agreements, land disputes, and, of course, the ball.

“It’s expected to be the grandest in years,” says one noblewoman, her fan fluttering as she leans toward her companion. “The southern provinces are sending their finest delegates. Even the Crown Prince of Aeloria might attend.”

I glance at my mother, seated at the head of the room, her expression serene but watchful.

She’s already made it clear what she expects of me: charm them, impress them, ensure they leave with no doubt of my suitability as heir.

“Your Majesty. Princess Aveline. Lady Claudine. The court is brighter for your presence. And some would say it glows more in yours, Princess. It must be the effect our noble Lady Claudine has on you.”

Lord Thibault’s voice draws me back to the present. He approaches with his usual confidence, bowing just enough to be polite. His dark skin and fine features stand out in the sea of diverse nobles, but his command of the room is unmistakable.

I caught Claudine’s gaze.

She didn’t speak—but her eyes told me everything. She knew his charm well, knew this polished chivalry for what it was. She’d seen it countless times in council meetings—and knew better than to be swayed by the gleam.

Especially from Thibault.

“Lord Thibault,” I reply, offering a faint smile. “I trust you’ve settled in well?”

“As well as one can in a palace where every wall seems to have ears,” he says, his tone light but edged with meaning. “A challenge, no doubt, Princess—keeping one’s own thoughts in this palace.”

Lord Thibault never enters a room quietly—nor does he speak without drawing invisible lines. That is how every council begins: with a duel dressed as diplomacy.

But today, I would not yield the first blow.

I rose from my seat, but not before my mother motioned for me to remain.

I ignored her directive and walked toward him, inclining my head and choosing my words carefully.

“The walls may listen, my lord, but the wise know what to say and what to keep silent.”

He chuckles softly, as though we’ve shared some private joke.

“Indeed, princess. A lesson worth remembering in times like these.”

“Lord Thibault,” my mother interjected smoothly, “you’ve always had a gift for remembering the right lessons—especially when they serve your moment.”

He turned slightly toward her, offering the faintest nod.

“And Your Majesty,” he replied, his tone respectful but cool, “you’ve always known how to turn a moment into a verdict.”

As he moved on, I caught Claudine’s gaze again from across the room. She gave a slight nod, her expression unreadable—but I knew what she was telling me: Stay alert. The room was full of whispers, and none of them were safe.

I didn’t turn to watch him go. That would have given him too much. Instead, I let my posture hold firm, chin lifted—not too high, not too proud. Just enough to remind the room I wasn’t afraid to be seen.

The whispers returned as soon as his boots faded into the marble hush. I didn’t need to hear them to know their shape.

A woman who speaks too little is cold. Too much, and she’s dangerous.

I intended to be both.

A Growing Power

The book doesn’t leave my side.

I know it’s reckless, but I can’t bring myself to hide it away again. Not when every glance at its pages feels like a door opening to a world I can’t yet see but desperately want to step into. I’ve spent every stolen moment studying its intricate drawings, its looping script. Most of the words are written in a language I don’t understand, but some—just a few—are in French. They speak of the land, of balance and growth, of thorns that protect and roots that bind.

I’ve started to notice things I didn’t before. When I walk through the garden, I feel the pull of the earth beneath my feet, faint but steady. When I brush my fingers over a rose bush, I swear the thorns curl back, as if to let me pass. And when I look at Madame Violette, something sharp and heavy blooms in my chest, like the book’s power is warning me to stay on guard.

This morning, she caught me lingering by the garden wall.

“What are you doing, girl?” she snapped, her cane tapping sharply against the cobblestones as she approached.

“Nothing,” I said quickly, shoving the book deeper into my apron pocket. “Just… weeding.”

She squinted at me, her thin mouth pulling into a frown.

“I told you not to go to the woods.”

Madame Violette’s voice was low, but every syllable landed like a stone dropped in water.

I said nothing. My fingers, tucked in the folds of my skirt, curled around the corner of the book still hidden beneath the fabric.

“You’re not like your mother,” Violette continued, taking a slow step forward.

“She knew her place.”

You didn’t know my mother, Cinder wanted to say.

But she swallowed it.

The air between us stilled. I didn’t shrink back. Not this time.

I stood my ground, the sun warm on my back, but the chill came from the stepmother in front of me.

Violette leaned in, her voice soft enough to draw blood.

“You think I don’t see it?” she asked. “That change in your eyes. That spark.” Her tone was velvet-wrapped steel. “Something’s shifted. Something wicked that I should fear: disobedience.”

I said nothing. Could say nothing. Not without revealing the book tucked beneath the floorboard. The pages that glowed faintly when my fingers brushed them.

“You’ve been wandering, girl.” A pause. “Into places your mother should’ve warned you about. Places no obedient girl with half a speck of subservience would dare go.”

At that, my jaw tightened.

“I am not like most girls.”

Violette smiled, but there was no kindness in it. Only calculation.

“I should burn whatever you brought back from that forest witch. The forest witch who lured your mother into hell knows what. And if you think you can spite me…”

I met her gaze then — fully, fiercely.

“You’d have to find it first…Violette. You don’t command me.”

The words hung in the air like smoke from a candle just snuffed out.

Neither moved.

The garden held its breath.

“Don’t let me catch you idling again. You have work to do. You really think you’re special,” Violette snapped, her voice brittle. “But you’re just like her. And that forest witch.”

I blinked.

Violette looked away too quickly.

“She made the wrong choice once. And now you wear her face like a challenge.”

As she turned away, the pull in my chest tightened, like a string drawn taut.

The whispers surged, sharper now, weaving into the memory of Esmée’s voice.

‘You’ll know what to do,’ she’d said as she pressed the grimoire into my hands.

Now, her words felt less like assurance and more like prophecy. Esmée had always been tied to the whispers—the hum of the land seemed to move with her. I wondered if she had been their voice all along, a guardian hidden in plain sight, guiding me toward the truth.

“Find the crown.”

The Weight of Expectations

I hate the way the courtiers look at me.

Their gazes linger too long, sizing me up like a prize to be won, their smiles just shy of predatory. At court, I am always being watched, always being judged. It’s exhausting, this performance they expect me to give. And the ball will only make it worse.

“Princess Aveline,” Claudine says softly, breaking me from my thoughts. She stands by the window, holding a silver tray with a letter sealed in deep blue wax. “This arrived just now. From the southern delegates.”

I don’t take it. Not yet.

“Why now?” I ask, though I already know the answer. My voice is quieter than I mean it to be. “Why must everything be timed around this ball?”

Claudine tilts her head, studying me.

I exhale slowly, the weight of everything pressing harder against my chest.

“All of this.” I gesture to the gilded walls, the heavy curtains, the polished performance. “The ball. The politics. The constant need to prove I belong in every room I enter.”

She hesitates, as if weighing her words.

“I think,” she says finally, “that simplicity is a luxury rarely afforded to those who can change the world.”

Her answer surprises me, but it doesn’t soothe me.

Change the world? Sometimes I feel like the world is too heavy to lift at all.

Outside, I hear the faint sound of Claudine’s voice speaking with a messenger. Her words are clear:

“Deliver this to Lord Thibault. He’ll want to see it immediately.”

My stomach tightens — though I’m not yet sure why.

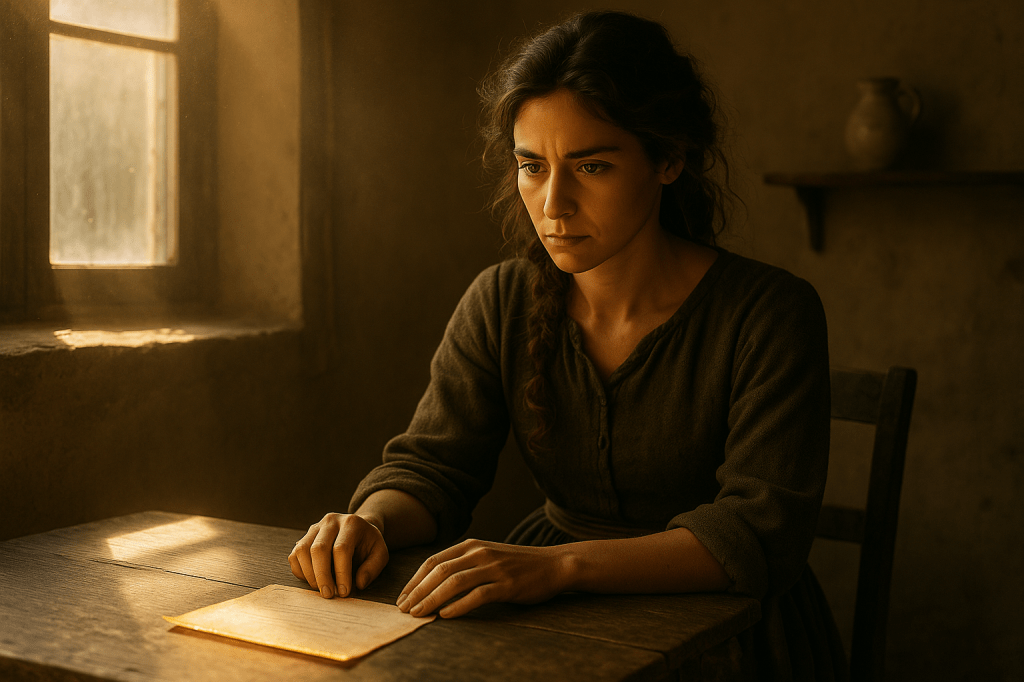

Foreshadowing the Collision

That night, as I sit by the hearth with the grimoire open in my lap, the whispers come louder than ever. They twist through the air like threads of smoke, their words half-formed, their meaning just out of reach. But one phrase cuts through the haze, clear and undeniable.

“She waits where the mirrors catch the stars.”

I don’t know what it means, but my pulse quickens all the same. The grimoire’s pages flicker in the firelight, and for a moment, I swear I see a reflection that isn’t my own.

The Hall of Mirrors feels different tonight. The chandeliers are unlit, the room dim and quiet, but the air is heavy, charged. I step into the center of the hall, my slippers whispering against the marble, and glance up at the high windows. The stars are faint but visible through the glass, their light shimmering faintly across the mirrored walls.

For a moment, I feel it—a presence, distant but palpable, like a whisper just out of reach. I shake my head, brushing it off as a trick of the light, but the feeling lingers, tugging at me like a thread I can’t see.

Preparations and Risk

The invitation came three days ago. It wasn’t meant for me, of course.

Madame Violette receives invitations to every grand event in the province, though she’s too reclusive to attend. This one arrived on thick parchment sealed with the crest of the royal family, gilded edges catching the sunlight as Aimée snatched it from the postman’s hands.

“Finally,” she’d said, holding the envelope aloft like a trophy. “A chance to show off my new gown.”

Sabine scoffed. “As if anyone at court would look twice at you.”

They bickered as they always do, their words sharp but shallow. I stayed silent, my gaze fixed on the invitation. The edges of the parchment glinted faintly in the sunlight, and for a moment, I thought I heard it hum.

When they weren’t looking, I stole it.

Now, the invitation sits beneath my pillow, its golden crest mocking me every time I look at it. I know I’ll be caught if I try to use it. I know the punishment will be severe. And yet, every time I think of the ball, I feel that same pull in my chest, that same hum in my ears.

I open the grimoire again, flipping to a page I’ve studied a dozen times since Esmée gave it to me. The symbol I saw before—the circle with thorns—sits at the top of the page, surrounded by stars and the faint outline of a rose. Beneath it, in elegant script, are words I don’t fully understand. But the meaning is clear enough: transformation.

The spell is intricate, far beyond anything I’ve dared to attempt. But it promises something I’ve never had: a chance to walk unseen, to step into another world without fear of being cast out. A chance to be more than Cinder.

The whispers rise again, threading through the air like a faint melody.

“Find the crown. She waits where the mirrors catch the stars.”

I steady my hands against the grimoire, its pages warm beneath my fingertips. The fear lingers, but the whispers’ pull is stronger.

End of Part 1

You must be logged in to post a comment.