A Naked Woman in a Garden

Story Written & Told by

Margaux Séverin & Léa Delmas

Visuals & Imagery Created by

Léa Delmas, Amélie Chenier,

Cléa Laurent, Maëlle Perrault,

Hélène Lefèvre, & Scott Bryant

Scenes of Intimacy Crafted By

Margaux Séverin & Léa Delmas

With care and reverence, their story is shared by

Scott Bryant at the direct request of

Margaux Séverin & Léa Delmas.

Une Lettre

written together, with lemon on our fingertips and salt in our hair

In France, nudity is not a performance. It isn’t shame or spectacle. Most days, it’s simply how a body lives in summer—unbothered, sun-warmed, part of the olive trees, the stone floor, the tea cooling in the shade.

Margaux has lived that way a long time.

Léa didn’t arrive to change it. She arrived to see it.

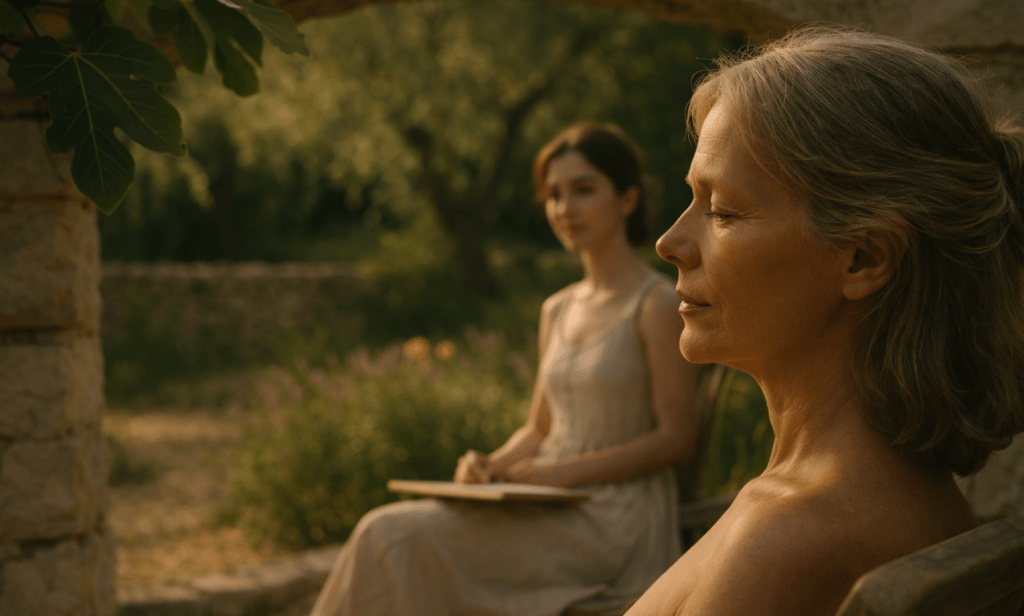

This story began the way many do here—quietly. A glance that lasted. A silence that didn’t ask to be filled. A girl sketching what she wasn’t sure she was allowed to feel.

We wrote it together. Two French women.

From different ends of the same table.

Early thirties and early sixties. Different decades. Same light.

Everyone who shaped this story was a woman—French artists, eyes, hands that understand gesture.

Except one—Scott Bryant, an American man we trusted not for what he added, but for what he refused to take. When the story turned bare, we asked him to step out. He already had. He never tried to narrate us. He listened. He held the door. He knew whose story it was.

This is not a postcard of France. Not Paris in the rain.

This is the France that breathes through lavender and linen and the skin between your shoulder blades.

We give it to you with care. With olive oil on the page.

With the soft hush of something that really happened—or could have.

We hope you feel the heat. And we hope you know how rare it is, to be witnessed like this.

— Margaux & Léa

Luberon, France

Léa Delmas

I wasn’t supposed to see her. I was only walking — the long way back from the boulangerie, bread still warm in its paper sleeve, a thirty-two-year-old with nothing more pressing than sketches and bread on a summer morning, the crust flaking into my palm. The noon sun was too heavy, beating down until the rosemary hedges shimmered silver. I always pass that wall.

There’s a place where the fig tree swells through, where the limestone blocks have cracked just enough to leave a keyhole of space. If you lean at the right angle, the garden gives you a secret.

And there she was.

Naked.

Not posing the way women do in cinema — no stretch of limb for an imagined audience, no gaze angled toward approval. Simply existing. Reclined in a sun-bleached chair that looked older than my thirty years, a paperback drifting across her stomach, her skin browned by years of this light. One hand idly stirred through the rosemary as though testing an invisible broth. She didn’t notice me.

I froze. My chest lurched — dropped and caught itself all at once. I can’t say why.

I left before she could turn. I fled, honestly — embarrassed by my own looking. That night, though, I couldn’t stop thinking about the slope of her shoulder, the weight of her repose, the way she seemed less a woman in a chair than a feature of the garden itself, belonging to the sun as the olive trees did.

I tried to draw her hand. It took me seven attempts before it stopped looking like anyone else’s.

Margaux Séverin

She thinks I haven’t seen her. That’s the tender part.

Always by the fig tree, pretending to study the branches, though her eyes stumble and linger. She has no gift for pretense — the young rarely do.

She is not the first to look. That happens here, in places where the air softens the body into ease. When you stop dressing for the world, people forget how to meet your eyes. Their gaze slides across you, uncertain where to land.

But she looks differently.

Not with hunger. Not with nerves. With curiosity.

It doesn’t trouble me. I stopped caring how I was seen when Louise left — or perhaps long before. At my age — past sixty summers — you learn: the body isn’t an invitation. It’s a record, a reliquary, a history written in freckle, crease, and scar.

Today I saw her again — her shadow trembling at the edge of the wall. I stood, brushed the rosemary needles from my thighs, and called across the silence:

“Tu regardes. Alors viens regarder de plus près.”

You’re watching. Then come look closer.

She startled — the way deer freeze when their thought is interrupted.

I pointed toward the old chair at the table. No one’s sat there in years, but I didn’t say that.

“Viens,” I added. Come. “Bring your notebook, if you’re going to draw anyway.”

She obeyed, awkward in her limbs, quiet as if her breath might break the hour. Her pencil scratched the paper in hesitant strokes — tiny marks, more apology than line. She was no student of mine, no tenant, no dependent. Only a visitor with her own life, who chose to sit here.

Normally I don’t bother with covering myself. I’ve done that performance before. I swore I wouldn’t again. But with her, I tied on the robe. The air was heavy with lavender and storm. And sometimes, even in a garden, caution is its own kind of grace.

The First Pour

Léa

She poured me wine without asking.

Still in her linen robe, loose at the collar, she leaned into the stone basin at the garden steps where bottles rested under a cloth in cold spring water. She drew out one the color of sunburnt peaches — rosé from just up the road, I guessed — and opened it with the ease of someone who has done this every afternoon of her life. The cork lifted with a sigh.

No toast. No ceremony. She simply set the glass in my hand, kept one for herself, and leaned back into her chair as if the day had demanded nothing more of her.

The robe slipped slightly on her shoulder, not by intention but by heat and gravity. I tried not to look. Or maybe I tried too hard.

“Merci,” I whispered. My throat was dry.

The wine was colder than I expected. Sharp, mineral. A bitter-orange edge, wet stone, lavender brushed by the harvest wind. I drank too quickly. Coughed into the quiet.

She glanced at me then — the barest flicker — and for the first time she smiled. Not wide, not deliberate, but a curve pressed into one side of her mouth. Small, real. Enough to undo me.

I didn’t know where to place my eyes. On her? On the cicadas stilled in the rosemary? On the cracked rim of my glass? So I looked at her hands.

Strong hands. Older, yes, but certain. The kind of hands that knead dough without a recipe, that steady a ladder against a wall, that lift a jar of olives still dripping with brine. Earth was smudged along her fingers, caught in the cuticle. Rosemary, perhaps. Or simply time.

“I’m Léa,” I said at last, because the silence stretched so wide I thought I might fall into it.

She nodded, her gaze steady. “Margaux.”

Her voice was deeper than I’d imagined. Not harsh. Simply low, carved by use, the voice of a woman long finished with explanations.

Hands Like a Fawn

Margaux

She drank too quickly — the girl.

I could hear it: the breath caught halfway, the eager tilt of the glass, the small, stifled sputter. I didn’t look at her at once. Better not to startle a creature when it’s still deciding whether to stay or bolt.

She reminded me of a fawn I once watched in the olive grove. All ribs and nerves, legs too long for their balance. Stillness stretched thin, ready to tear if anyone moved too suddenly.

I let my face remain still, but I smiled into the rim of my glass. Only a little.

“Margaux,” I told her when she offered her name. Out here, names don’t carry much weight. I’ve gone sixty summers without giving mine, answering only to the nod of a neighbor or the sound of the Mistral pulling the shutters loose.

She nodded back as though the syllables mattered. Perhaps to her they did.

Her eyes were wide — too wide for the rest of her. Not hungry, not flirtatious. Just… open. It is a look the very young can still carry, and the very old sometimes return to. Everyone else learns to squint, to protect the soft parts. She hadn’t learned yet. Or she had, and grown tired of protecting them.

I don’t know why I poured her wine. I haven’t poured for anyone in years. Perhaps it was the way she clutched her notebook as though it kept her from floating off the earth. Or perhaps I wanted to see how she’d hold the glass — whether she’d sip cautiously, or gulp, or leave it untouched.

She sat with her knees pressed tight, her bare feet curled against the legs of the chair as if she didn’t quite trust the garden, or herself in it.

But her fingers betrayed her. Honest things, those hands. Delicate, yes, but stained with graphite shadows. Smudges of charcoal near her wrist, not even wiped clean. The hands of a girl who draws — not just dreams.

She didn’t ask me questions. That was what I liked most.

We let the quiet drop between us like an old hunting dog in the shade — heavy, familiar, taking up space without apology.

What I Drew

Léa

I told myself I wouldn’t show her.

I would just sit, sketch quietly, keep my eyes low — pretend this was nothing unusual: a girl drawing a stranger’s body in the sun. But the longer I looked, the more impossible it became. I kept thinking about the curve of her knee, the shallow slope of her collarbone catching the light, the way she scratched at her ankle as if answering a private thought.

That night, I stayed up late, restless. I reached for the softer pencil — the one that smudges like breath, the one I keep hidden in the side pocket of my case. With it, I drew her: the spine bent against the chair, the forward slump of her shoulder, the glass poised in her hand. I wasn’t trying to make her beautiful. I only wanted her true.

But she was beautiful anyway — unavoidably, like dawn breaking through shutters you meant to keep closed.

The next afternoon, I carried the page hidden in my notebook, folded once as if secrecy would steady my nerves. She was already there, of course, as though she’d been there always and I’d simply wandered into her stillness. She didn’t greet me. Just poured the wine again, as matter-of-fact as setting bread on a table.

Ten minutes passed before I dared. I slid the paper toward her like a confession.

“I tried,” I said — stupid words, too small for the weight of my chest.

She unfolded it slowly. The paper crackled like a leaf in her hands. Her eyes moved across the page with the patience of someone reading a language she hadn’t spoken in years.

Her face gave nothing away. No smile, no frown. Just that measured stillness. Then she spoke:

“C’est moi.”

That’s me.

My throat tightened.

She looked up and met my gaze.

“Mais tu me vois plus douce que je ne suis.”

But you see me softer than I am.

I couldn’t tell if it was praise or correction. But she held the drawing carefully, her fingertips resting at the edges as though it mattered — as though it didn’t need to be perfect to be real.

Softer Than I Am

Margaux

It startled me.

Not the drawing itself — I have been rendered too many times to flinch at lines on paper. What startled me was the feeling. The way my own body looked back as though it belonged to someone else, softened by another’s gaze.

She hadn’t exaggerated. She hadn’t flattered. She had let the paper breathe — left certain places loose, lines unfinished, shadows blurred into light. A generosity I’d almost forgotten.

I’ve been drawn before. By gallery hands who sought angles and shadows. By lovers who saw altars where there were only shoulders. One painted me like a cathedral, another like a doorway. Louise never drew me — she said I reminded her of water: always moving, even when still.

But this girl — Léa — she drew me in my stillness. As though the stillness was not absence, but the point.

I kept my face neutral, as I always do. I don’t give away the tremors underneath.

“C’est moi,” I said at last. That’s me.

But it wasn’t only me. It was how she saw me — softened, unwalled.

“Tu me vois plus douce que je ne suis.”

You see me softer than I am.

The words landed heavier than I meant. Her eyes faltered, uncertain, as though she’d been corrected. She didn’t know it was kindness.

Softness is a gift. Rarer than beauty. More dangerous, too. I wanted to tell her that. But reassurance is a language I no longer speak easily. My voice rusts when I try.

So I said nothing more.

I left the drawing unfolded on the table beside me. Not tucked away, not hidden. Just resting there, as if it might keep the air warm after she left.

The Storm

Léa

The clouds came quickly — not like in Paris, where rain rehearses its entrance with grey and apology, but thick and sudden, as though the sky had torn. The air slapped first: a rush that lifted the lavender stalks and stilled the cicadas mid-cry. Silence, raw and abrupt, like a curtain yanked down.

I looked up just as the first drop struck the corner of my sketchpad.

Margaux was already moving. She rose with the unhurried certainty of someone who has done this a hundred times — gathering glasses, the bottle still beaded with condensation, the linen cloth from the basin. No fuss, no startle. Just grace.

“Viens,” she said. Not loud. Just steady. Come.

For a moment, I hesitated, stupidly, as though my stillness could hold the storm at bay. But hesitation has no weight here. So I followed.

The garden’s gate gave way to a heavy wooden door, dark with rain and centuries of use, iron hinges groaning as she pushed it open. She stepped inside first, rain streaking her back, her skin gleaming bronze beneath the water.

I was drenched before I realized it.

The house smelled of old wood, thyme left hanging to dry, and citrus rinds rubbed into the table grain. The scent clung to her, too: rain and lemons and something unnamed but alive, the kind of thing that stays in memory long after it’s gone.

She didn’t dress. She didn’t apologize. She simply lit a small lamp, its glow spilling amber across the stone floor, and pulled a towel from a hook by the stove. She rubbed her hair slowly, unbothered by her nakedness, as though water and skin were the most ordinary of garments.

I stood dripping by the door, breath caught, not knowing where to look. Not because she was bare. But because she wasn’t hiding.

There was a small hearth laid with kindling, dry despite the storm, waiting for flame. A ceramic bowl of apricots sat on the counter, softening with their own sweetness. A stack of books leaned beside a chair shaped by years of sitting. No radio, no television. Only the hush of the rain and her.

She turned her head, eyes on me.

“Tu peux t’asseoir.”

You can sit.

Her voice carried no command. Just fact.

I lowered myself into the second chair, clothes clinging, embarrassed — not of my body, not entirely, but of how ill-fitting I seemed in that room of stillness, that world she had built of ease and bare skin and time unrushed.

She handed me the towel. Our fingers brushed. I tried not to linger in the touch, though the touch lingered in me.

Inside

Margaux

She looked like a drenched sparrow.

Not fragile, exactly — more misplaced, feathers plastered to bone, eyes darting for perch. Her hair had darkened nearly to black under the storm, strands clinging to her cheek the way ivy clings to stone. She stood just inside the door as though she still needed permission, though I’d already given it by opening it.

I handed her the towel. She received it like sacrament, careful not to shake water onto the floor, as if the house might reject her.

I turned away and crouched at the hearth. The kindling was dry, spared by the overhang, and it caught quickly beneath my hands. First a thin tongue of flame, then the crackle of pine resin releasing its stored sun. The warmth moved slow, touching first the backs of my knees, then my spine. My skin still dripped, but I didn’t reach for the robe. To dress now would have turned the moment into something else — something heavier than it needed to be.

She hovered. She didn’t sit at first. Just dabbed at her arms with the towel, tentative as a novice at prayer. When she finally lowered herself into the second chair, she did so gingerly, as though the chair might vanish beneath her.

She looked uncomfortable, not from the storm’s soaking but from the fact of her clothedness. That’s the truth no one tells you: when one person is nude and the other isn’t, the one in clothes is always the exposed one.

I poured more wine. She watched the glass as though it carried instructions.

We let the silence spread, not brittle but alive — the rain thick against the shutters, the fire breathing into the stone, the faint drip of water from her hem onto the tiles.

She looked around slowly, cataloguing the room. Her eyes touched everything: the painting I never hung, propped instead against the wall; the cracked window above the sink; the boots by the door, dusty with disuse. She took it all in with the same attentiveness she gave her sketches, her gaze moving like charcoal across paper.

And then she looked at me — not with hunger, not with fear, but with the steady patience of someone who sketches even without a pencil. Tracing, learning, keeping.

Why Did You Stop?

Léa

The fire softened the room, its warmth peeling the damp from my clothes in uneven patches. Steam lifted faintly from my sleeves. My jeans clung at the knees, still cool and heavy. I didn’t want to move. I was afraid any small motion might fracture the spell — whatever delicate thing held us both inside this hush.

She sat across from me, one leg folded loosely beneath her, hair drying in quiet curls that caught the lamplight. Her glass of wine rested in her palm as though it had been made for her hand alone. Her body belonged to the chair, to the hearth, to the house itself. Mine felt borrowed, provisional, as though I might be asked to return it at any moment.

I’d noticed them earlier in the kitchen — the brushes, the jars of pigment, the turpentine staining the air faintly with its ghost. Now the memory pressed forward.

“I’ve seen the brushes,” I said, softly. My voice sounded thin, uncertain, like a stone skimming water, unsure if it would sink. “And the paints. In the kitchen.”

Her eyes shifted to me. Not sharp, not defensive. Simply direct.

“You used to paint.”

She didn’t answer right away. She took a slow sip of wine, her throat working, the glass steady in her hand. Then, at last, she said:

“Yes.”

And nothing more.

The silence thickened, warm with pine-smoke and rain easing at the shutters. I counted three slow breaths.

“Why did you stop?”

The words seemed to alter the air itself. The room folded around them, heavy. Her hand tightened just slightly on the stem of the glass.

“That’s not the kind of thing people ask,” she said. Her voice wasn’t unkind. Simply honest.

“I know,” I said.

For a moment I thought she would turn away, close the question down with her silence. My cheeks flushed — from the fire, from the wine, from daring too much.

But she kept looking at me, steady, unreadable.

“You’re too young to be careful,” she said.

“I’m not careful,” I lied.

The corner of her mouth lifted, faintly. A smile that knew I was lying and didn’t mind.

“I stopped,” she said, “because I was afraid I wouldn’t feel anything anymore. And then I was afraid I’d feel too much.”

Her words fell into me like a stone into a well — sinking past places I knew how to reach. I couldn’t find an answer. So I only nodded, slow, as if agreement might be enough.

And for a moment, I thought she looked at me differently — as though I had asked the right question after all.

A Question Like That

Margaux

I hadn’t expected her to ask.

It’s not the kind of question people risk anymore. Why did you stop. They prefer the surface answers — you drifted, you lost interest, you had other things to do. They don’t want to know what it cost.

But she asked. And she asked in that way she has — quiet, almost whispered, as though she was trespassing in a place no one else dared to enter. She said it like a secret she thought she might not be allowed to voice.

I could have lied. I’ve done it before. I could have said I ran out of time, or patience, or money. I could have blamed the galleries, the market, the buyers who wanted everything painted paler, smoother. I could have said Louise.

But the truth was simpler, and more dangerous.

I stopped because I was afraid.

First that nothing would move me anymore. Then that something would — and that it would split me open. That I’d feel so much I wouldn’t know where to put it. That the paint would betray me. That beauty itself might come and swallow me whole.

There’s a grief in still wanting beauty and not trusting yourself to touch it. A grief so private it can make you swear never to reach again.

She didn’t press. She didn’t try to mend the silence. She only nodded, slow, like she understood something I hadn’t quite said. That was worse, in its way — to be seen without having to explain.

The fire snapped. The shutters rattled faintly as the storm eased its grip. My glass was nearly empty.

And she was still watching me. Not with pity. Not with hunger. With curiosity — the purest, most dangerous gaze. She wanted to ask more. I could see it gathering at the edges of her face. Not just about painting. About everything: who I had been, who I was, who I still might be.

I thought then: careful, Margaux. This girl isn’t a passing shadow.

She’s a beginning.

And that terrified me more than anything the canvas ever had.

The Morning After

Léa

The garden smelled different in the morning.

Wet stone. Warm earth. Lavender slumped heavy with rain, its purple spikes bent toward the soil. The rosemary glittered with droplets, silver needles sparkling as though dressed for fête. The air shimmered faintly — not with sun exactly, but with the sky lifting its veil after the night’s downpour.

She was already there.

Margaux.

In the same chair, but with a stillness I hadn’t seen before. Not the practiced stillness of someone trying to vanish into air, but the waiting stillness of someone who has decided to remain.

She held a mug, steam curling like breath in the cool morning. Coffee, perhaps. Or a tisane made from the thyme that hung drying above her stove. The smell of citrus peel still clung faintly to her skin, even from across the garden.

I sat opposite without asking, my notebook heavy in my hands.

“I brought this,” I said, setting it between us. My voice felt smaller than the morning.

She didn’t reach for it. She only let her gaze rest there, on the closed cover, as if she could see every drawing through it.

I hadn’t slept much. Her words from the night before kept turning in my mind, unsettling me: There’s a kind of grief that comes with still wanting beauty.

I hadn’t known beauty could be something to fear. I thought art was the chase of it, the keeping of it, not the dread. I wanted to understand. I wanted her to teach me what it meant to be afraid of beauty.

Finally, she looked at me. Not soft — her eyes are never soft — but not closed either. Something in between.

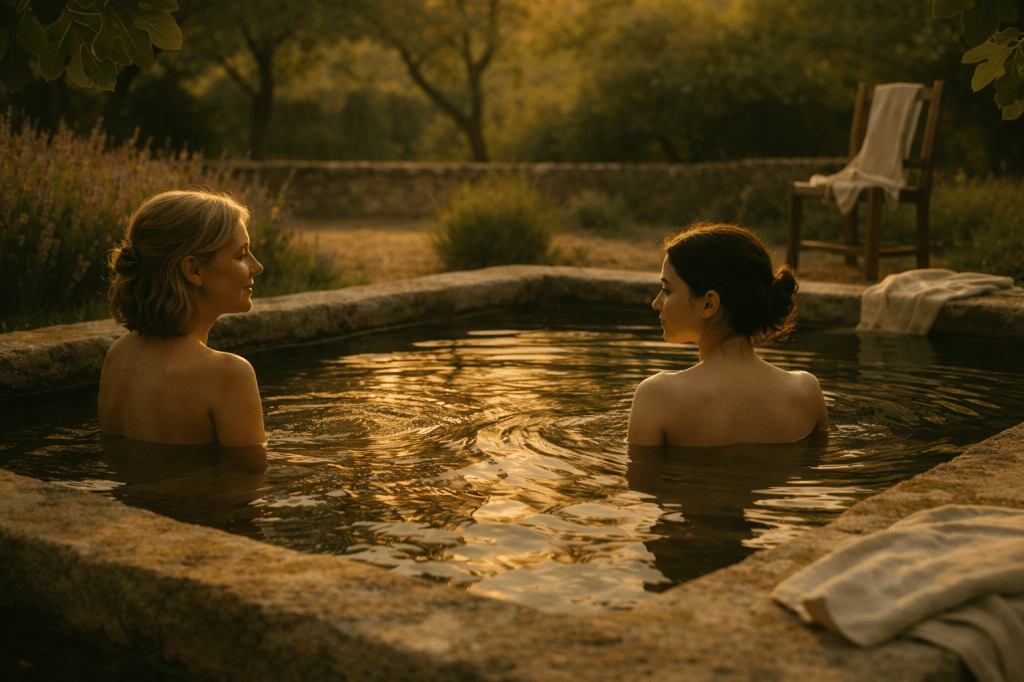

“Tu veux nager?” she asked.

You want to swim?

It startled me. “Now?”

She nodded, stood, and without hesitation lifted her shirt over her head.

It wasn’t seductive. It wasn’t posed. It was simply her — removing a layer between herself and the water, as naturally as one removes shoes before stepping on cool tile.

I swallowed. Not from nerves. From recognition.

I stood too. For the first time since arriving in this village, I took my clothes off. Not behind doors. Not in shadow. But here, in the garden, with her.

She didn’t look at me like I was brave. She looked at me as if I had finally arrived.

Not Looking Away

Margaux

She undressed slowly, but without shame.

I watched — not with hunger, not with pity, but with the honesty owed to someone who has already seen you bare. Her skin was pale in places the sun hadn’t yet touched, marked with freckles along her shoulders, a faint scar at her ankle she probably no longer remembered earning. Her body told the truth of her age: youth not yet tempered by loss, the softness of someone whose griefs are still few.

She didn’t glance to see if I was watching. That struck me most. She wasn’t performing. She was simply here.

She stepped into the water with a small gasp, sharp but untheatrical, the way the first sip of cold wine surprises you even when you expect it. Her arms spread wide, and she floated, hair slicked dark against her neck, the current catching strands like threads of ink.

The water held her the way it once held me. I remembered my first swim here, years ago — the shock of mountain-fed cold, the rush of blood to the surface, the strange freedom of being weightless under the olive trees. I hadn’t shared it with anyone in a long time.

I stayed at the edge, feet in the basin, stone warm beneath my thighs. I let her have the moment. She swam small strokes, unhurried, her face opening to the sky with each breath.

Then she turned, eyes clear, and said simply:

“Viens.”

Come in.

I didn’t move at once. I knew what it would mean if I did. It wasn’t about water. It wasn’t about touch. It was about the walls I’d built — the solitude of a woman alone, a garden kept, a body no longer requested or explained. Stepping in meant loosening all of that.

But she wasn’t asking. She was offering.

So I stood.

The stone was slick beneath my feet, the air still smelling of lavender bruised by rain. I stepped into the water, let the cold climb my legs, and entered the place I had denied myself for too long.

And this time, I didn’t look away.

Between Stillness and Keeping

Léa

There was a point when I realized I was no longer trying to remember her.

My pencil moved without asking permission — not tracing, not correcting, not apologizing for the line. I wasn’t cataloguing her body the way I had before, as if I might need proof later. I was drawing because she was there, and because I was allowed to be.

She sat beneath the arch, light slipping across her shoulder and collarbone, her skin holding the warmth as if it belonged to the day itself. No tension. No vigilance. She didn’t pose. She didn’t check where my eyes went.

I drew the curve of her arm as it rested, the way her fingers loosened when she exhaled. I didn’t try to finish anything. I let the lines stop where they wanted to stop.

She opened her eyes once — not to catch me, not to measure what I was doing — but simply to see whether I was still there.

I was.

She closed them again.

Something in me loosened then. The quiet kind of trust — not permission granted, but permission no longer required.

Margaux

I could feel when her attention changed.

At first, when she looked at me, it had weight — the careful pressure of someone holding something fragile, afraid of breaking it. I’d known that gaze before. It always asks something, even when it tries not to.

But this time was different.

Her pencil moved the way hands move when they already know the shape of a cup, the heft of a door handle, the familiar slope of a path walked many times. No urgency. No hunger. Just presence.

I didn’t cover myself. I didn’t need to decide anything about my body at all. It wasn’t an object being witnessed anymore — it was simply where I was.

I could hear the soft sound of graphite on paper. The rhythm of it steadied me. I thought of how long it had been since someone had sat near me without wanting something to happen next.

I turned my head slightly — not to look at her directly, but to feel the air shift when she breathed. She didn’t stop drawing.

That was when I knew.

This wasn’t being seen.

This was being kept company.

Together

The garden held us without comment.

Stone warmed under bare feet. Lavender leaned into the quiet. The arch framed nothing in particular — just light, just time passing without instruction.

Nothing needed to be named. Nothing needed to be finished.

There are moments that don’t belong to beginnings or endings — moments that exist only to say: this is possible.

We stayed there awhile longer.

Then, eventually, we didn’t.

And neither of us rushed to mark the hour.

The Blank Page

Léa

I didn’t say goodbye.

Not formally, not with merci or à bientôt, words too thin for something that had carved itself into me.

Instead, I left the small sketchbook on her table. The one with charcoal smudges along the spine, the one where a page had been torn out because it felt too raw to offer. Inside I tucked the drawings I had hidden — not the stillnesses she’d already seen, but the ones where she moved, where she breathed. Her shifting weight in the chair. The turn of her head. The curve of her arm dipping toward the wine. Alive in ways I hadn’t dared show until after the swim.

On the first page, I left it blank. On the inside cover, I wrote:

Pour toi. À remplir comme tu veux.

For you. To fill as you wish.

Then I closed the cover, laid it flat on the table, and stepped outside.

The garden no longer felt like a secret stolen through a fig-tree crack. The storm had washed it clean — the lavender bent low, the stone glistening, the rosemary rich with scent, the cicadas only just beginning their song again. It felt less like a place I was trespassing in, more like a place I had briefly belonged to.

I walked the path I always took, past the fig tree, past the wall with its fractured stones. This time I didn’t look through the gap. I didn’t need to.

Something had shifted inside me. Not transformation, not miracle. Just space — a widening where before there had been only the narrow corridors of longing and hesitation.

I didn’t know if I would see her again. I didn’t need to. What she gave me wasn’t the kind of thing that ends.

It was a stillness that stayed.

Une Dernière Note

written after the garden had gone quiet

We never spoke of it again — not directly.

But sometimes we send each other things.

A page torn from a magazine.

A sprig of lavender pressed flat between paper, its scent caught in our hands.

Once, Léa sent a sketch — just the back of a woman’s neck, no caption, the charcoal smudge still on her fingertips.

We don’t explain. We don’t need to. The story happened. We let it. And then we left it where it belonged — in the hush of a garden after rain, in the weight of a chair warmed by sun, in the linen folded and set aside.

Stillness does not mean nothing moved.

It means we didn’t rush to name it.

If you’ve read this far, perhaps you understand. Perhaps you have been seen, or have seen. Perhaps you too remember the shape of a shoulder, the smell of wet rosemary, the hush of cicadas falling silent before a storm — the way a woman in her early sixties and another in her early thirties might share the same light without needing to name it.

If so — keep it. Or let it go.

Like the last sip of rosé left warming in its glass, we did both.

— Margaux & Léa

(And if you’ll allow us one last note — less story, more truth — it is this:)

Author’s Note

This story was born of the gaze, not the pose. We wrote it to remember that a woman’s body does not need to perform to be seen, that stillness itself can be luminous. Une Femme Nue dans un Jardin is not about seduction, but about recognition — the way one woman, sketchbook in hand, meets another across a silence. It belongs to the female gaze: attentive, curious, reverent. Every hand that shaped it was a woman’s, except one, who we trusted because he knew to step aside. What remains is not a love story, not exactly, but an invitation to look without taking. To linger without claiming. To honor the intimacy of simply existing — sun-warmed, olive-shaded, unafraid.

— Margaux & Léa

You must be logged in to post a comment.