The Ferry at the Wrong Hour

I take the first vapur because it asks nothing of me.

At this hour, no one looks twice. The women who clean offices have already crossed back, their shoulders slumped, their eyes dulled by fluorescent light. The students are still asleep, phones charging beside their beds. The city is between versions of itself, and so am I.

The iskele at Beşiktaş smells of damp concrete and yesterday’s tea. A woman rinses paper cups into a drain, the liquid running dark and bitter before disappearing. A cat sleeps on the warm lid of a vending machine, one ear flicking when the engines begin to hum.

I tap my kart and walk on without thinking. I always sit inside. Outside invites conversation, and I have learned not to accept invitations I don’t intend to keep.

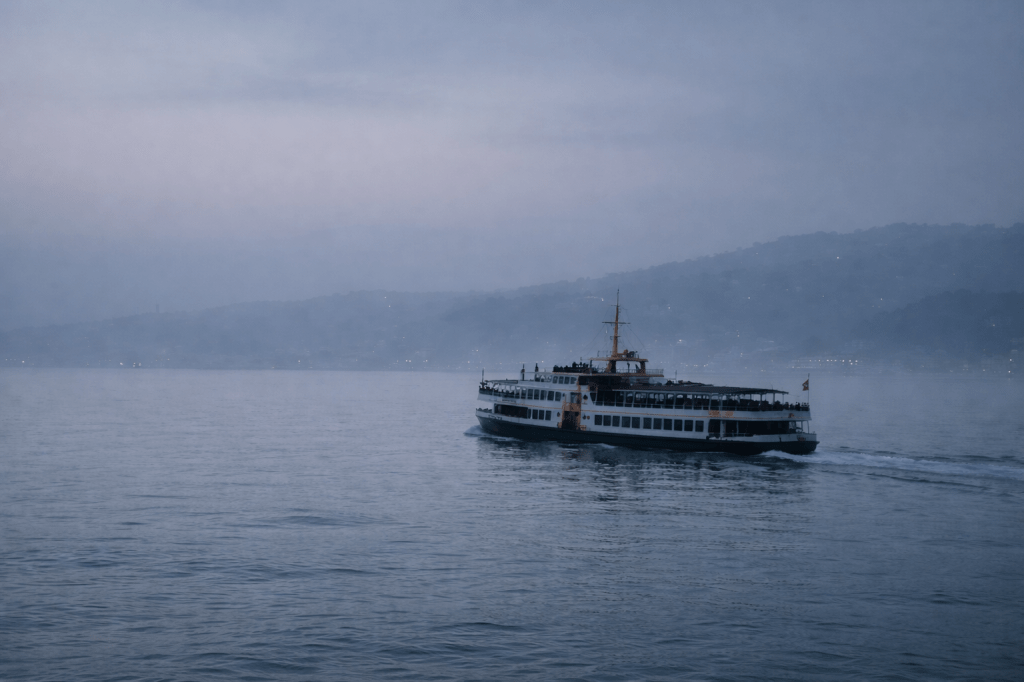

The ferry pulls away with a shudder that travels up through the soles of my shoes. I choose the window seat on the right, the one that lets me watch the water without being seen too clearly. Asia waits ahead, a darker line against the thinning sky. Europe loosens its grip behind us.

I count crossings the way other people count days. I stopped counting days a long time ago.

Someone pours çay nearby. The smell cuts sharp and familiar, like a memory that refuses to soften with age. The glass clinks against its saucer. A gull lands hard on the railing outside, bold and loud, as if it owns the morning.

I watch the wake spread and flatten, spread and flatten, until it looks like it has always been that way.

This hour protects me. I chose it carefully.

People assume reasons. Night shifts. Early meetings. A sick relative across the water. No one imagines what they are not taught to imagine. No one imagines someone riding simply to avoid arriving anywhere that matters.

The ferry settles into its rhythm, engines low and steady, like breathing that belongs to someone else. I rest my forehead briefly against the cool glass. My reflection overlays the city—my face floating over mosques and apartment blocks, over cranes paused mid-reach. I look like a woman passing through herself.

She boards two minutes after we leave the dock.

I know this because the balance of the room changes.

It is not the sound of her steps that draws my attention. It is the pause that follows them. The brief hesitation people make when they enter a space and decide how much of themselves to bring inside.

I do not turn around. I have practiced not turning around.

Her coat brushes the back of my seat as she passes. Wool, damp at the hem. She smells faintly of soap, the cheap kind that leaves a clean, almost medicinal edge in the air. She does not sit immediately. I see her in the window first—only the curve of her cheek, the dark line of her hair pulled back too tightly to be comfortable.

When she sits, it is one row behind me, offset. Close enough that I can hear her breathe if I listen for it. Far enough that she does not have to acknowledge me.

I tell myself this means nothing.

The ferry rocks gently as we cut across the current. The lights along the shore blur and steady. Someone murmurs günaydın to no one in particular. A phone vibrates and is silenced quickly, almost apologetically.

I think of the other ferries I could have taken. Earlier. Later. Faster. Slower. I chose this one because it exists in a narrow window. Because it lets me move without deciding.

I feel her attention before I hear her voice.

“You always sit here,” she says.

She does not raise her volume. She does not lean forward. She speaks as if continuing a thought we have already agreed upon.

I keep my eyes on the water.

“I like the window,” I say. My voice sounds the way it always does at this hour—flat, serviceable, unadorned.

“Yes,” she says. “And because no one can sit on one side of you.”

I swallow. I hadn’t realized this was something I had been doing until she named it.

The ferry horn sounds—low, warning, indifferent. We pass beneath it like something small and temporary.

She says my name.

Not as a question.

I turn then. Slowly. As if speed might make it worse.

Her face is ordinary in the way faces become ordinary once you look at them long enough. No sharp beauty, no immediate threat. Her eyes are tired, but focused. She looks like someone who has already decided what she will carry and what she will leave behind.

“You don’t have to be afraid,” she says, gently. “I’m not here for that.”

“For what?” I ask.

She considers this, watching the water slide past.

“For the part you’re pretending not to be,” she says.

The ferry begins to slow. I feel it in my knees, in my chest. The announcement crackles overhead, distorted but familiar, Üsküdar stretching itself into sound.

Across the glass, my reflection steadies. For the first time that morning, it does not look like it might drift away if I stop watching it.

She doesn’t look at me when she says it. That’s the part that makes it worse.

The ferry leans into its turn, the floor tilting just enough that people shift their feet without realizing they’ve done it. A woman near the door tightens her grip on the rail. Someone laughs softly, surprised by their own imbalance. The city does this to us all the time—moves slightly, waits to see who adjusts.

I face forward again. Outside, the water has lightened to a dull silver, the surface broken by the ferry’s wake and the impatient wings of gulls that follow us without affection. I know better than to ask how she knows my name. Knowing has never required permission.

“You’re mistaken,” I say. It’s what I say to everyone. Employers. Relatives. Strangers who think they recognize me in the wrong place.

She hums, almost kindly. “If I were,” she says, “you wouldn’t be here this often.”

I press my thumb into the edge of my bag until the seam bites back. Inside are things I never use on the ferry—keys, a notebook, a pen that no longer writes unless you coax it. I bring them anyway. Proof of a life that continues beyond this crossing, even if I don’t visit it very often.

“People commute,” I say.

“Yes,” she replies. “But they arrive.”

The engines drop in pitch as we approach the middle of the strait, that brief stretch where the water feels deeper, colder. I have always imagined this as the most honest part of the crossing. No shore close enough to pretend you belong to it. No dock waiting to forgive you.

A woman passes selling simit from a tray, the rings still warm, the sesame seeds clinging stubbornly to her fingers. I shake my head without looking. Hunger feels like another obligation I don’t have room for.

The woman behind me does not buy one either.

“You don’t eat on the ferry,” she says. Not accusing. Observant.

“I don’t like crumbs,” I answer.

She smiles at that, and I hate myself a little for noticing. “You don’t like evidence.”

The city slides by, patient and uninterested in our conversation. I catch sight of a mosque dome emerging from the low light, its curve softened by distance, by years of seeing it from angles that never require me to enter. The call to prayer will come later, when the day has committed to itself. Right now, there is only the hum of the engines and the small, human sounds we pretend not to make.

“What do you want?” I ask finally.

She considers the question as if it deserves the courtesy of thought.

“Nothing,” she says. “That’s the problem.”

I turn again despite myself. “Then why speak to me?”

“Because you’ve mistaken quiet for disappearance,” she says. “Because you think the hour does the choosing for you.”

Her words land without force, without drama. They are not sharpened. They do not glitter. They are simply accurate.

I look down at my hands. The skin around my nails is cracked from the cold. I pick at it until it stings. Pain, at least, has boundaries.

“You don’t know anything about my life,” I say.

“I know you stopped crossing for someone,” she replies. “And started crossing instead.”

A gull slams into the railing outside, wings flaring, metal ringing sharp and sudden.

The ferry horn sounds again, shorter this time.

The shoreline of Üsküdar sharpens into detail—ferry ropes coiled and waiting, a woman pacing the iskele with her hands in her pockets, the glow of a tea stall just beginning to assert itself against the morning. Asia rises to meet us, solid and unbothered.

I stand too quickly, my balance off. She reaches out without thinking, her fingers closing briefly around my sleeve. The contact is light, almost accidental, but it steadies me more than it should.

“I’m not asking you to follow me,” she says quietly, releasing her grip as if she never touched me at all. “I’m only asking you not to pretend this hour is empty.”

Around us, people gather their things. Zippers open. Bags are slung over shoulders. Lives resume their forward motion. Someone mutters a complaint about the cold. Someone else checks the time and sighs.

The announcement crackles overhead, a woman’s voice flattened by the speaker.

She stays seated.

That is the final, unbearable thing.

She does not perform departure. She does not offer herself as a path. She remains exactly where she is, as if she has already crossed and has nothing left to prove.

I step into the aisle. The ferry shudders as it docks, the sound traveling up through my legs, into my spine. The doors open. Cold air rushes in, sharp and decisive, carrying the smell of the street—bread, exhaust, wet stone.

At the threshold, I stop.

Behind me, the ferry waits. So does she.

Ahead, the iskele hums with the small urgency of morning, with footsteps and voices and the promise of being required somewhere.

I stand between them, feeling the hour thin around me, no longer protective, no longer neutral.

For the first time, I understand that staying seated is also a choice.

And that the ferry, indifferent and patient, will make the crossing again whether I am on it or not.

Recorded during an hour that does not ask to be explained.

—

Archived on scott-bryant.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.