The Violet Hollow

Story Written & Told By

Elise Harrow

Visuals & Imagery Created By

Sasha Rezende, Avery Monteiro,

Marisol Viera, & Scott Bryant

With steadfast loyalty, Elise’s story is shared by

Scott Bryant, at the request of Elise Harrow, Jocelyn Andrade,

& Sloane Rosario

Liner Note:

This work has been prepared for public release with the consent of all named contributors. All accounts remain as told by the originating witness. Recorded in the quiet season at Castine, 2024–2025.

Property of the Violet Hollow Circle. Unauthorized duplication is discouraged.

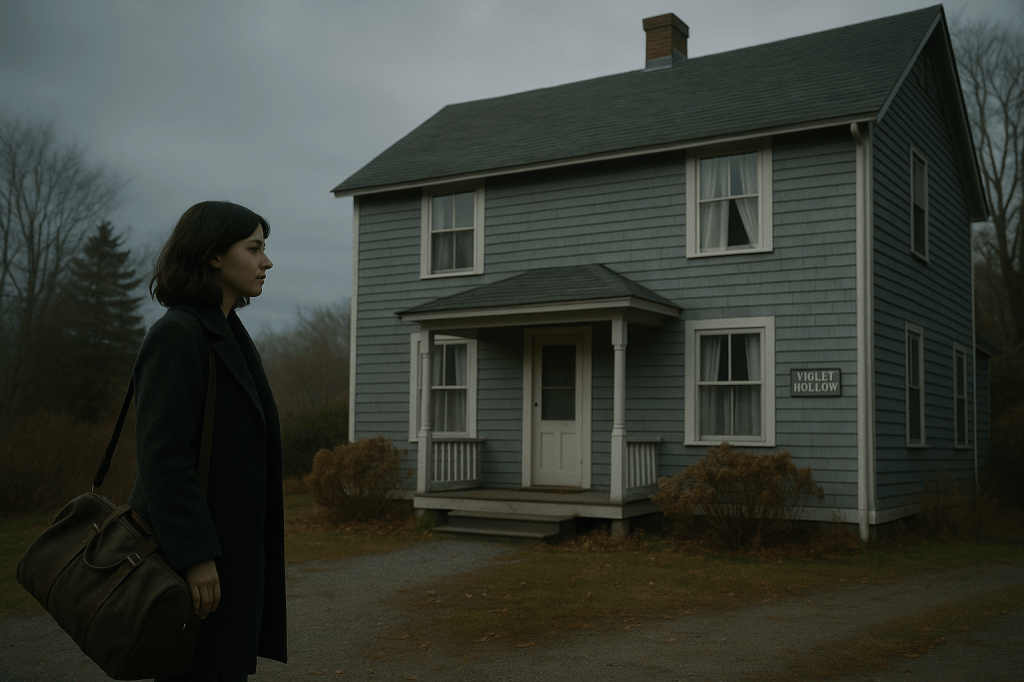

The Violet Hollow

I’ve stayed in stranger places — a converted lighthouse in Maine, a cabin where the wind howled like a dog, even a rental with a fridge that groaned like a dying opera singer.

After the quiet collapse of a three-year relationship with a woman I loved — and my own restless need to keep moving — I booked a cheap, off-season Airbnb in Castine. A place where I could work without distraction.

Back in Boston, I layer field recordings and archival audio for sound installations and podcasts. I’ve met, loved, and built exciting relationships with many queer women, but I’ve always been restless — always chasing the next sound, the next place.

A girl’s girl with an ear for every note, you could say.

Here, there would be only the wind, the sea, and whatever I could catch on tape.

The Violet Hollow was charming in a dated way. Clean. Quiet.

The kind of quiet that doesn’t just sit —

it listens back.

I passed the bedroom on my way to the kitchen — the scarf from the photos was folded on the bed.

Ten minutes later, tea in hand, I paused in the doorway. It wasn’t on the bed anymore.

Now it was draped over the chair by the window.

A Faint Noise

The Airbnb description said it was built in 1952 by two women who lived here together for the rest of their lives. The female host hadn’t said much else — just that the place had “good bones” and “a lot of love in the walls.” It didn’t sound sentimental, exactly. More like a fact.

I’d scrolled through the photos more times than I’d admit. All the standard coastal-rental charm — wood floors, floral curtains, mismatched mugs — except for one detail: a silk scarf, ivory with tiny embroidered violets, appearing in a different spot in nearly every shot.

Sometimes draped over a chair, folded on a bed, or hanging from a doorknob. In one frame, the door stood half-open; in the next, it was open just enough for the scarf’s edge to trail into shadow. Always placed where a person might stand or pass by.

And sometimes the light was wrong — afternoon sun in one photo, gone in the next — as if the room itself had shifted between shots.

As I set my mic case down, a faint scent — floral and powdery — brushed past me, gone before I could place it.

I’d just unpacked my gear — mic, recorder, headphones, the usual — when I also heard it.

Faint at first, curling in from the back bedroom.

Not just any melody.

“I know… I know… you belong to somebody new…”

I froze.

That was my voice. Exactly my tone, my breath, my scratch at the end of “know.”

I know what my own voice sounds like, even when I don’t want to hear it.

And I hadn’t sung a note.

This is the song — the Dottie Evans and Audrey Marsh take — warmer, lower, carrying that private sort of sweetness, like two women leaning close over the same microphone.

I knew the recording. 1956.

The house was built in ’52 by the women who lived here the rest of their lives. Which meant this wasn’t a song from the year they moved in – it was four years later.

Long enough for the furniture to wear in, for routines to take root.

Long enough for a scarf to have a favorite chair.

If you know the recording — the Dottie Evans and Audrey Marsh take — you’ll understand why I froze.

Night 1: Catching Something on Tape

I slipped the headphones around my neck and thumbed the recorder on.

If it was a neighbor’s radio bleeding through the walls, I’d catch it. If it was something mechanical — faulty wiring, a loose ground loop — I’d catch that too.

The song kept drifting in, sweet and faint:

“But tonight… you belong to me…”

It wasn’t tinny like a speaker.

It was warm, close.

The way a voice sounds when someone’s leaning in, singing just for you.

“If this was a trick, it had chosen the wrong listener.”

I padded down the hall, recorder rolling. The closer I got to the bedroom, the more certain I became — it wasn’t coming from a corner or a vent. It was coming from the center of the room.

I stepped inside.

Silence.

Not the natural kind — not the faint hum of a fridge, or the bass note of a building settling.

The air felt cooler, a draft carrying the faintest shiver as if someone had just passed by. A low flicker from the lamp caught my eye — a pulse, not a failure.

This was the kind of silence that presses up against you, waiting to see what you’ll do next.

I scanned one of the rooms — nothing out of place. Just the neat double bed, a nightstand, an old dresser with a doily draped over it. I bent down, checked under the bed. No hidden speaker.

I straightened up, glanced at the recorder display. Nothing but the low hiss of ambient noise.

That’s when I caught it — faint, almost below hearing range.

A hum.

Not from the walls.

From somewhere much closer.

From me.

I touched my fingers to my throat.

Nothing.

No vibration.

But when I parted my lips, just enough to breathe, a thread of the melody slipped out like steam from a kettle. I felt it low in my ribs, the way you feel a bass note more than hear it — soft, steady, unshakable, the start of a hum you can’t stop once it’s begun — a vibration seeping under the skin, as if my own body was the instrument.

“…although… we’re apart…”

I snapped my mouth shut. The sound cut off instantly, but the pressure of it stayed, like a word I couldn’t swallow.

This wasn’t sleep deprivation. It wasn’t a trick of acoustics. I’d recorded underwater caves that made cleaner sense than this.

“Okay,” I whispered, to the empty room. “You win round one.”

I packed the recorder away, telling myself I’d set up a contact mic tomorrow, maybe even leave it running overnight. But I already knew — deep down — whatever this was didn’t want to be caught on tape.

And that was the part that unsettled me. Not the singing in my own voice. Not even the way the lyrics had landed just right, like someone knew exactly what they meant to me.

It was that it had stopped the moment I realized I was listening.

Night 2: This Doesn’t Belong to Me

I left the recorder running in the kitchen that night, just in case. I told myself it was for the work — every soundscape artist needs a library of oddities — but it was really because I wanted proof.

I was halfway through brushing my teeth when it started.

Faint, at first — just the opening notes curling through the hallway. My voice again, steady and clear:

“I know… I know… you belong to somebody new…”

I spat into the sink, wiped my mouth, and reached for the headphones. I’d catch it this time.

Then it happened.

A second voice slid in under mine — warm, low, and rich in a way I could feel along my spine.

“…but tonight you belong to me…”

I froze in the doorway. It wasn’t just harmony — it was perfect harmony, the kind you only get when you’ve sung with someone for years.

The voices blended so seamlessly I couldn’t tell where mine ended and hers began.

“…although… we’re apart… you’re a part of my heart…”

I stepped into the hallway, recorder lifted like a divining rod. The sound didn’t fade as I moved — it followed, like the two of us were walking together, singing to someone neither of us could see.

When the song reached “my honey, I know”, I swear I felt breath warm against my ear.

I turned.

No one.

But I was no longer sure the “no one” applied to me.

The last note lingered in the air like perfume you can almost name but can’t.

As it faded, the air shifted — floral and powdery, brushing past my cheek as if someone had just passed.

I turned, expecting emptiness. And found only that faint, lingering scent — sharper now, as though it had bloomed in the air itself.

I hit stop on the recorder. Scrolled back. Listened.

Nothing. Just the hum of the refrigerator, the creak of the old house. No voices. No melody.

I glanced at the scarf again, the violets catching the kitchen light. Somewhere in the back of my mind, the harmony replayed itself without my permission — that low, steady voice meeting mine on “…but tonight you belong to me…”.

I told myself it was just the memory of the song. But my throat felt warm. Too warm.

Night 3: Sensory Slips

By the third night, I’d stopped pretending I was here to work.

The portfolio edits stayed untouched in my laptop. My attention belonged to the house — and to her.

I set the recorder in the bedroom this time, a contact mic pressed against the old dresser. If the song wanted to play games, I’d play along.

The first verse came just after midnight. My voice again, threading through the dark, steady as breath:

“I know… I know… you belong to somebody new…”

Her harmony followed instantly, smoother than the night before, like she’d been rehearsing.

“…but tonight you belong to me…”

I sat up in bed, heart quickening — not from fear, but recognition. The phrasing was ours now. She’d matched my inflections, my timing, like we’d been singing together for years.

When the line came — “way down along the stream” — the air shifted.

The walls were the same pale yellow as when I’d arrived — but the framed landscape above the bed was tilted now, just slightly, like someone had bumped it passing by.

As I moved toward it, I caught my reflection in the dresser mirror — just for a heartbeat. The tilt of the head didn’t quite match mine. Softer, older, wearing something pale at the throat. Then it was gone.

The dresser now held a porcelain dish of hairpins. A hatbox leaned against the far wall.

Folded neatly, was a wool coat in a deep, midnight blue.

Draped over the back, almost as an afterthought, was the violet-embroidered scarf.

The floral and powdery scent from that first night curled through the room, hitting me just before I noticed it had been waiting for me all along.

I stepped out of bed, bare feet on cool wood. The song went on, my voice and hers winding around each other, as I reached for the coat.

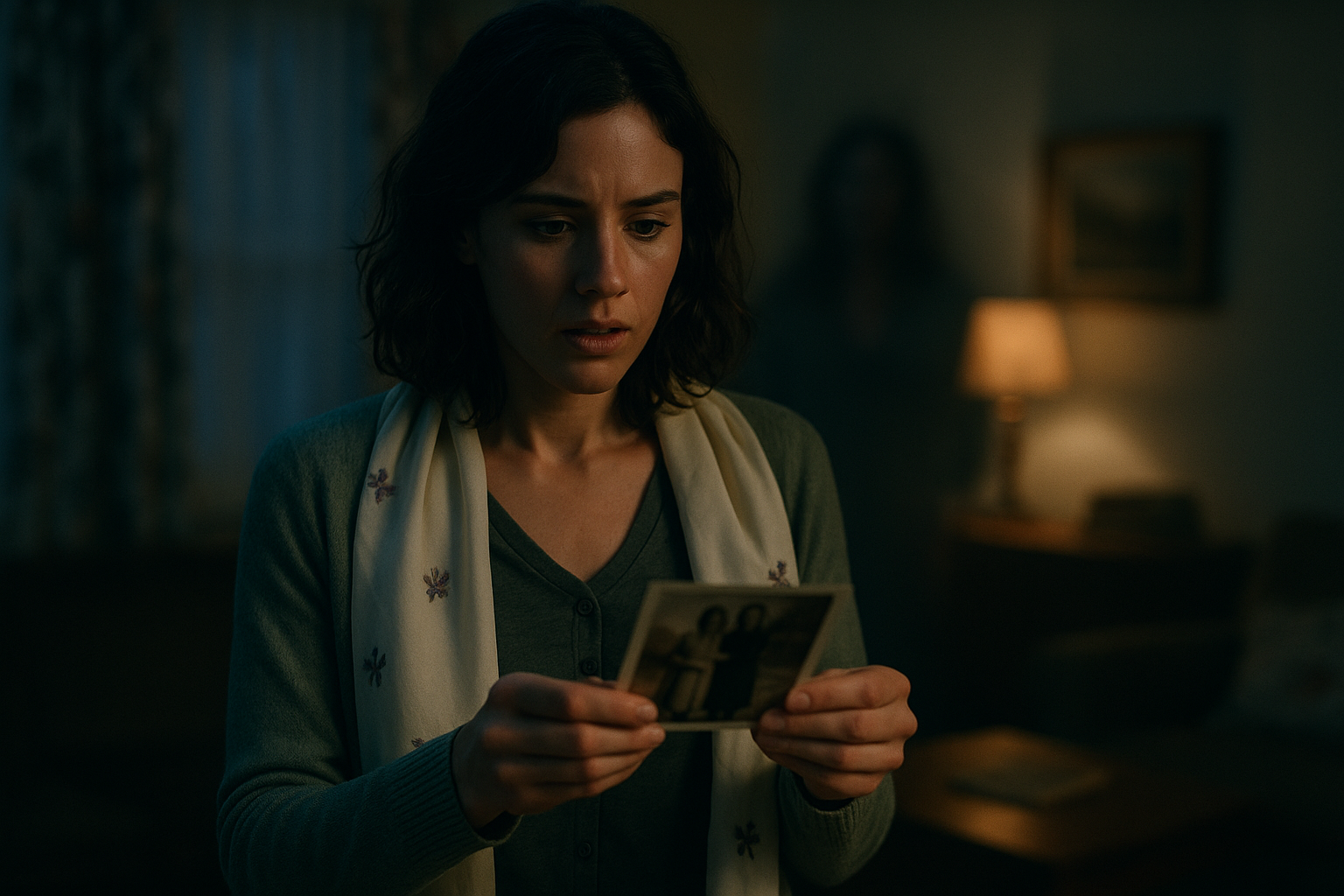

Inside the pocket was a black-and-white photograph — two women in a summer garden, one with her arm around the other. Both smiling like they knew a secret.

Draped over one woman’s shoulders, faint even in the grain, was the same ivory scarf with its tiny embroidered violets. The other woman’s gaze caught me — not just because she was looking straight into the lens, but because her expression was familiar. Not memory-familiar. Mirror-familiar.

The coat pocket was warm.

The Final Night

The fourth night, I didn’t bother setting the recorder.

I didn’t need proof anymore. I wanted the song.

I left the bedroom door open and sat in the living room with the scarf draped over my shoulders, the photograph on the coffee table beside me. I’d been staring at it for hours, memorizing the tilt of their heads, the way one woman’s fingers curled possessively at the other’s waist.

The first note rose in the stillness — my voice, as always. But it didn’t sound like it was coming from down the hall. It sounded like it was coming from inside my chest.

“I know… I know… you belong to somebody new…”

Her voice joined instantly, warm and close enough to feel against my cheek.

“…but tonight you belong to me…”

I sang with her this time.

Not out loud — but the words formed in my mouth, lips moving in perfect sync. The air seemed to hum around us, the house leaning in to listen.

When we reached “way down along the stream”, the walls seemed to ripple. The pale yellow paint deepened into wallpaper patterned with faded roses. The furniture shifted, reshaped. The coffee table became an upholstered bench.

We were no longer in the Airbnb.

We were in their living room.

Not the rental’s version – theirs. The air carried the faint hiss of a record player between tracks. Somewhere, the clock on the mantel read a time that had passed decades ago, and the calendar on the far wall still held a September of 1956.

She stood beside me — I couldn’t make out her face, but I knew the curve of her shoulder, the scent of her hair. I could almost see her leaning toward the record player, lowering the needle to where the song would begin.

Her hand brushed mine, deliberate and sure.

The familiar scent from the first night curled through the air — soft, cosmetic, and unmistakably human — a cue before the words.

“My honey, I know…”

She didn’t sing the rest. She whispered it, right against my ear, and it bloomed around us like breath made visible.

And I whispered back.

Somewhere Behind Me

The scarf still rested around my shoulders — ivory, with tiny embroidered violets — catching the morning light, holding the ghost of warmth as if it had just been worn.

Floral and powdery.

Fresh now — sharper than it had been in the night, as though someone had just passed behind me.

It felt heavier than it should have, the weight not quite fabric’s — more like a hand had settled there, gentle but unwilling to let go.

I packed without thinking, tucking the photograph into my bag. The recorder was empty — except for the faintest sound under the static, a single hum that might have been mine.

Or hers.

Or both.

I locked the door behind me, stepped into the cool morning air.

Somewhere between the driveway and my car, I realized I was humming — soft, steady, unshakable — the same hum I’d felt in my ribs that first night, the way you feel a bass note more than hear it.

My fingers were already in my jacket pocket, curling around my phone — half-ready to hit record without thinking.

“I know… I know… you belong to somebody new…”

…and then, in the space between breaths, a hum — warm, close—braided into mine.

The kind of quiet that doesn’t just sit —

it listens back.

Somewhere behind me, the air shifted — just enough to carry a note I wasn’t singing.

At the next gas station, I stopped for coffee and unzipped my bag, thinking I’d look at the photograph one more time.

It wasn’t there.

My eyes flicked to the scarf — still folded in the seat beside me. I hadn’t even touched it, yet some part of me had already braced for it to be gone too.

I told myself the warmth in the scarf was just from the sun, but the air in the car felt thicker — softer — like the quiet you only hear on a record between songs.

Somewhere, under the hum in my chest, I thought I caught the faint crackle of a needle finding its groove.

I glanced at the rearview mirror, just for a second — and for that second, the tilt of a woman’s head wasn’t quite mine. Familiar, but not memory-familiar. Mirror-familiar. Then it was gone.

Just the faint scent of something floral and powdery — sharper now, as if it had bloomed in the air between one breath and the next.

“…but tonight… you belong to m—”

You must be logged in to post a comment.