The Crucible

Tualatin High School Theater Department —

March 8th & 15th, 2025

Tualatin High School Auditorium, Tualatin, Oregon

Directed by Jenn Hunter Tindle

By Arthur Miller

Notes from a high school production where history and reinterpretation collided.

Some plays feel like history lessons. Others feel like warnings. Tualatin High School’s The Crucible was both — staged with conviction, urgency, and a surprising resonance that made it worth archiving.

First Impressions

The program already hinted at depth: director Jenn Hunter Tindle, in her Director’s Notes, recalled her own first encounter with Arthur Miller’s play in high school, and how the story functioned as both history (the Salem witch trials) and allegory (McCarthyism). That dual lens shaped the entire performance.

The minimalist production design carried the audience back to what one assumes is the 1950s — signaled by the pre-show and intermission song choices — the very decade when Miller was reckoning with hysteria and false narratives. Instead of Puritanical costumes, it was a modern, rural setting where farmers, community, and rigid faith were tested. What struck me most, though, was how those echoes felt alive in 2025 — in a year where polarization and the spread of misinformation still dominate public life.

Why This Production Stands Out

Performed by high school students, yes — but this staging was not a retelling. It highlighted the play’s enduring themes of unchecked power and mass hysteria while also reflecting the values of a new generation. The casting choices spoke volumes, making this what I would call the strongest ensemble I’ve ever seen in a high school production. What gave it force was not just individual performances, but the way the company worked as one. Voices overlapped, energy collided, and silence was wielded as power.

It felt less like a school play and more like a collective reckoning — carried by one of the most talented groups of Gen Z actors I’ve ever witnessed. They know firsthand what it means to come of age in a world shaped by chaos, misinformation, and polarization. And in that recognition, Miller’s warnings stopped feeling like history. They became present tense.

Editorial Note: I name adult directors and performers in public, professional contexts. Out of respect for privacy, I do not publish the names of student actors.

Performance Highlights

Reverend Samuel Parris was played by a non-binary student (they/them), adding complex dimension to a role traditionally defined by patriarchal male authority. Here, Parris became less a caricature of rigid faith and more a study in hypocrisy and insecurity — fragile, rather than commanding. Their performance carried a sense of poetic justice: a non-binary actor reclaiming and subverting the very figure who, in history and in the text, so often demonizes the marginalized. What emerged was less the voice of spiritual authority than a mirror held up to fear itself — fear as theater, fear as power, fear as pretense.

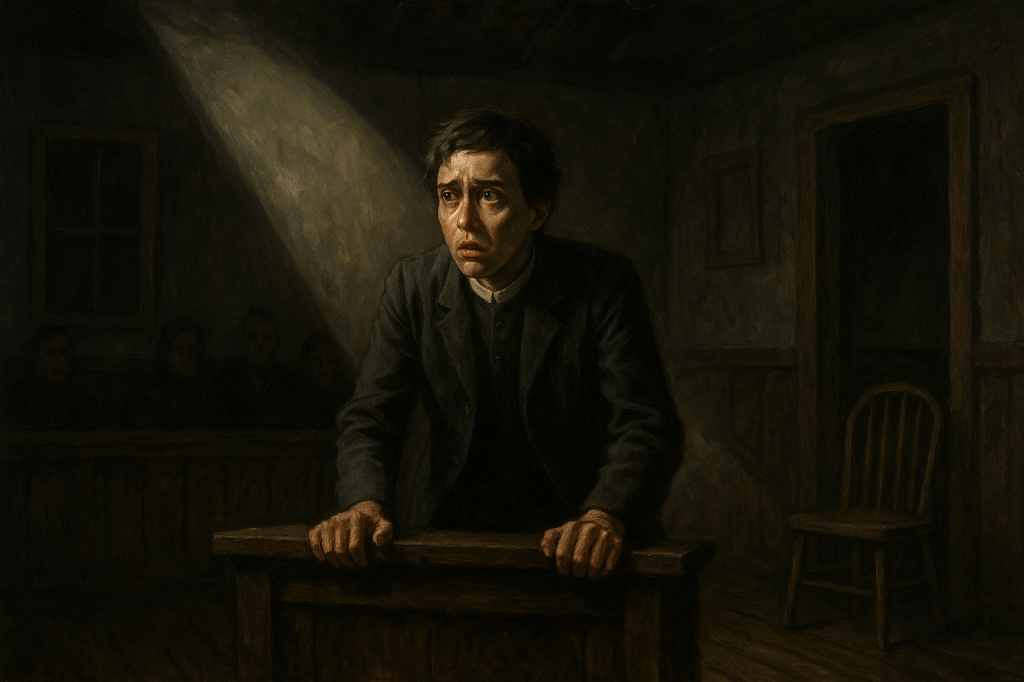

The performances of John Proctor and Deputy-Governor Danforth — especially in what I call “Act 3: The Trial” — were unlike anything I had seen from young actors before.

So often mistaken as a hero, Proctor instead emerged here as a morally insecure, tormented man clinging to patriarchal ideals and control over Elizabeth Proctor, Mary Warren, and even in his strained exchanges with Reverends Parris and Hale.

His presence revealed the burning red flags of a man desperate to preserve authority while hiding behind a conflicted conscience — an insecurity that came to explosive clarity in the courtroom.

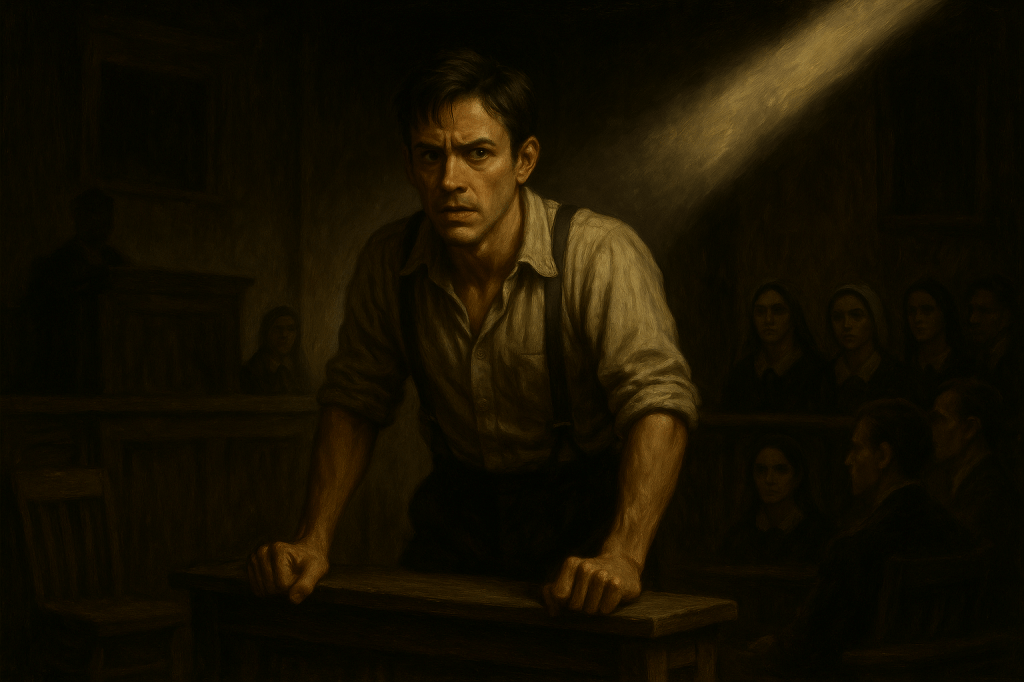

Proctor has been immortalized on professional stages and screens — from Daniel Day-Lewis’s brooding in the 1996 film to the late George C. Scott’s severity in the 1967 TV movie. The name ‘John Proctor’ even inspired American playwright Kimberly Belflower’s 2022 Broadway debut, John Proctor is the Villain, a modern re-imagining set in a high school that (rightfully) centers the voices of young women. Yet this Tualatin student actor carved a space of his own. His Proctor did not imitate; it unsettled. It felt born not of tradition, but of the present moment — and it left its own mark. One can imagine, someday, the role itself belonging to a woman — another landmark in the ongoing reinterpretation of Miller’s text.

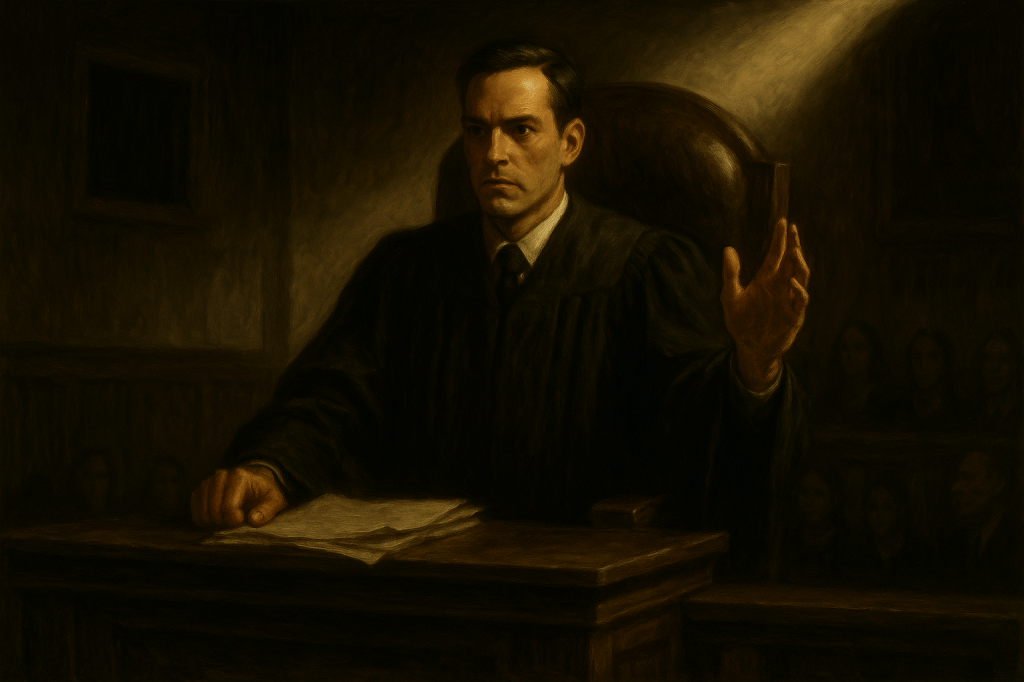

Danforth, by contrast, orchestrated the courtroom with theological certainty, leaving the chilling impression that no one could ever receive a fair trial in his world. Yet this was no recycle of the rigid, Shakespearean-toned judges of the past. Instead, this Danforth bore the quick mind and prosecutorial speed of someone itching for convictions, his questions snapping like traps. It felt less like regal gravitas and more like the relentless pace of rumor, gossip, and misinformation in today’s social media age. One slip in his courtroom meant immediate doom. In this interpretation, Danforth became less a relic of Puritanical law and more a terrifyingly modern figure — a performance that could rival even the Oliviers of the stage.

Other roles — Reverend Hale, Judge Hathorne, Constable John Willard, and Francis Nurse — were embodied by young women. This reshaping shifted the balance of power on stage, underscoring how gender and authority are never fixed, but interpreted anew each time the play is staged.

The intensity of Tituba, Betty Parris, Mercy Lewis, and Susanna Walcott carried raw urgency, reminding the audience that the machinery of hysteria often begins in the voices of the young.

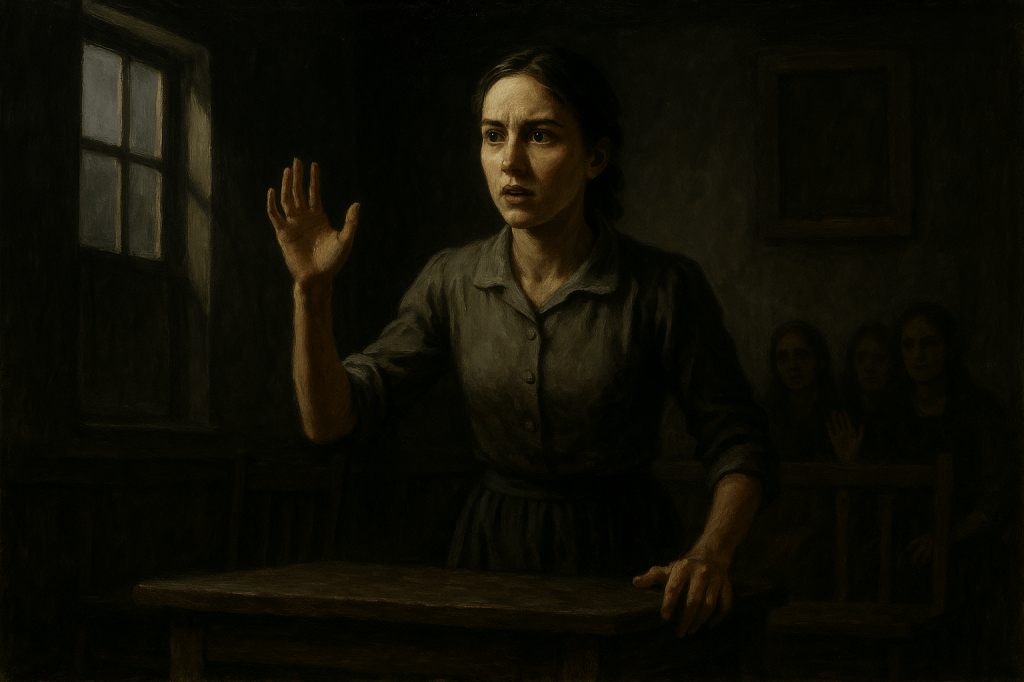

With Abigail Williams, her desperation and fire made her feel less like a stock villain and more like a tragic, abused figure — someone whose fear and longing drew more sympathy than many of the supposed adults around her. The playbill even noted that the student in this role had previously won “1st place in State with a group scene from The Crucible” and considered Abigail Williams the role she cherished most.

The same needs to be said for the student playing Mary Warren, the object of Proctor’s crushing, gaslighting control. While one is often led to believe Warren collapses under the weight of Proctor’s horrific verbal oppression, in this version it was Warren who ultimately turned the tables — in dramatic, heroic, and satisfying fashion. In one scene, a simple poppet — thought to be the hysterical source of dark magic — became the spark that set the climactic courtroom showdown ablaze. It was a reminder that even the smallest voices and roles can make the biggest difference.

If Oregon high school theater had its own version of the Tony Awards, this Crucible — and especially the performances of Parris, Proctor, Danforth, Williams, and Warren — would surely be contenders.

Even the performance of Giles Corey held its own, offering a brief touch of levity in an otherwise harrowing story. A particularly memorable moment in Act I came when Corey lamented about everyone suing everyone else, yet boasted of his six court appearances that year — including suing Proctor for four pounds in damages for accusing him of burning a roof. Proctor’s sharp retort lamenting about how saying good morning to Corey meant being dragged into court for defamation in comical hysteria drew hushed laughter. The exchange reminded the audience that even amid fear and hysteria, Miller wove in contradictions and comic relief that make his characters strikingly human.

Multimedia Highlight

Among the preshow and intermission songs was Kip Taylor’s “She’s My Witch,” a bluesy track that underscored the production’s 1950s framing. Its presence — playful, eerie, and slightly off-kilter — reminded the audience that even in its quietest moments, this Crucible was steeped in atmosphere.

During act transitions, recordings from the McCarthy hearings were played, collapsing the distance between Salem and Washington, 1692 and 1954. The voices of real senators and witnesses bled into Miller’s dialogue, reminding the audience that the mechanics of hysteria and false accusation are not just allegory, but documented history.

Archival Note: When Arthur Miller first staged The Crucible in 1953, it was an allegory for McCarthyism — hysteria weaponized to destroy lives during The Red Scare. Seeing it in 2025, performed by Gen Z students, the allegory stretches further. This is a generation raised in the thick of misinformation, polarization, and cultural battles over identity. Their performance didn’t treat Miller’s warnings as relics; it refracted them through the urgency of their own moment. In their hands, The Crucible felt less like a classroom exercise and more like an urgent act of interpretation.

Why It Belongs in the Archive

What made this production unforgettable wasn’t just Miller’s words, but the way they were embodied by a new generation: non-binary voices, young women inhabiting authority, students refusing to let the past stay sealed in history.

This was The Crucible not as a relic, but as living theater — both a warning and a reclamation. That is why it belongs in my archive.

Archival Meta Note: I rarely see the same play twice, but I returned for The Crucible. Once might have been enough to admire the conviction, but twice made it a reckoning. Returning wasn’t only about catching details — it was about affirming that this student production deserved the same seriousness as any professional stage. In going back, the act of archiving shifted from observation to participation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.