Dial M for Murder

Clackamas Repertory Theatre — September 20th, 2025

Osterman Theatre – Oregon City, Oregon

Adapted by Jeffrey Hatcher, Directed by Karlyn Love

From the original by Frederick Knott

Notes from a Saturday matinee, when Margot and Maxine carried the heart of the story.

Archival Preface: Theatre vanishes the moment the curtain falls. What remains are fragments — playbills, programs, highlight reels, memories carried home. I write these notes not as a critic, but as an archivist of experience: preserving what I saw, what mattered, and why it deserves to be remembered.

This is not a review in the traditional sense. It is an archival record of a single Saturday matinee — a performance where Margot and Maxine carried the heart of the story.

Some productions leave you entertained; others leave you with memories worth preserving. Clackamas Repertory Theatre’s Dial M for Murder falls firmly into the latter. What follows are my impressions and archival notes on a matinee that reframed a classic.

First Impressions

Holding the bright, razor-edged program in my hands, I knew I was stepping into something more than a cozy mystery.

The set was stunning — a London flat of warmth and menace. Golden drapes and a tufted sofa promised comfort, but doorways framed like traps and corners holding shadow suggested danger. And by the door, Margot’s cream coat and Maxine’s black coat hung together — silent proof of their bond, unnoticed by the men around them.

Why This Production Stands Out

This staging earns its place in my archive not only for its taut suspense, but for how it reframed a familiar thriller through a distinctly feminist lens.

Director Karlyn Love emphasized in her playbill letter that mysteries endure because they promise justice — the guilty are punished, the innocent go free — something life rarely guarantees.

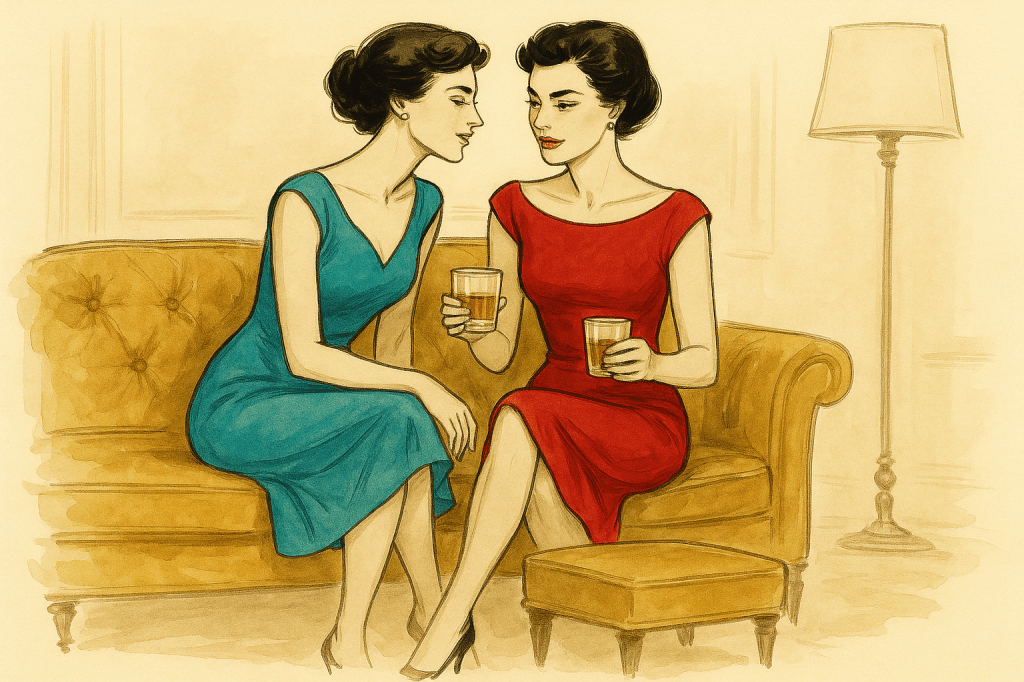

Fashion sketch, imagined scene from Dial M for Murder

In this rendering, the intrigue pauses. Margot, dressed in teal, leans close to Maxine, whose crimson gown anchors the composition in boldness. Both hold glasses, their shared gesture suggesting not indulgence but ritual — a moment of stillness carved out within the turbulence of the play.

The illustration echoes mid-century fashion plates, yet its focus shifts the narrative: the women are not defined by peril or suspicion but by recognition of one another. The chromatic dialogue between teal and red embodies balance — composure meeting passion, secrecy meeting strength.

Here, the thriller is reframed as portrait. What might once have been background becomes the heart of the story: intimacy not as subtext, but as center stage.

Her direction sharpened that idea, ensuring Margot Wendice and murder mystery writer Maxine Hadley were not sidelined as victims or plot devices, but instead carried the heart of the story. Their relationship, their secrets, and their survival became the true tension of the play, transforming blackmail and betrayal by men into something deeper and more resonant.

Margot & Maxine

The moment that crystallized this shift was small and radical:

Margot and Maxine shared a kiss.

“Night, sweets,” Maxine whispered before leaving for her BBC interview — an invitation Margot declined. What once might have been scandal was here simply love. Not spectacle, but recognition.

The accompanying sketch captures the moment’s essence — the elegance of restraint, the charged intimacy, the way posture and gesture told a story beyond words.

Ink and wash on paper, fashion-plate style

This restrained yet radical sketch captures a kiss exchanged between Maxine and Margot — a moment once unthinkable on stage, reframed here as quiet recognition rather than scandal. The composition emphasizes symmetry and stillness: two women leaning in, balanced like mirror images, their intimacy rendered not as spectacle but as authenticity.

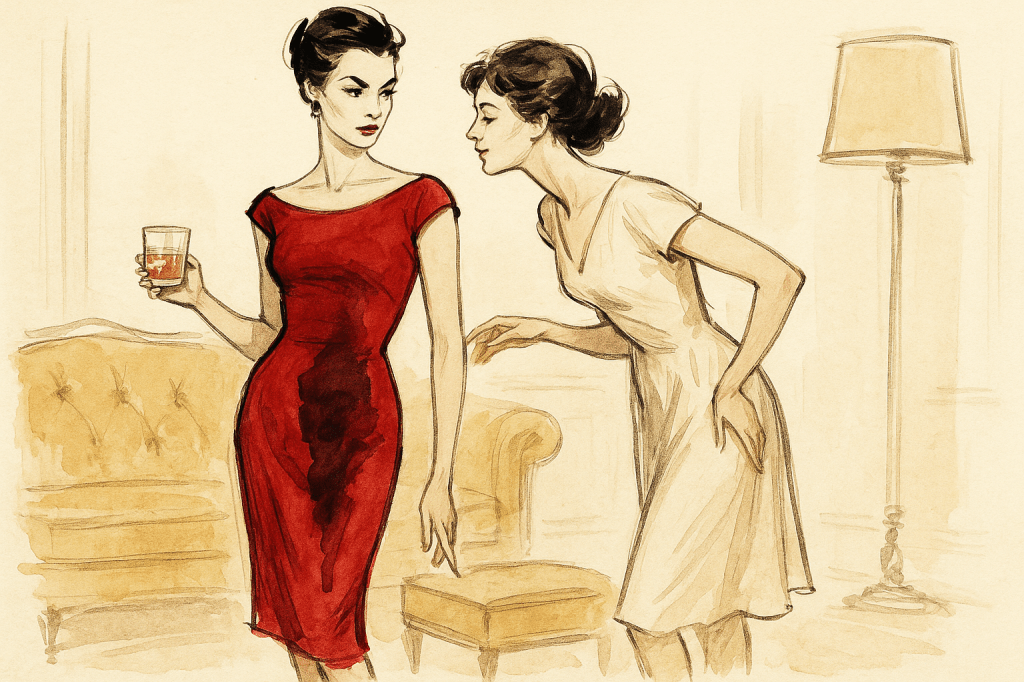

One subtle but unforgettable moment came in the first act, when Tony accidentally spilled his bourbon on Maxine’s crimson dress. Margot whisked Maxine into her bedroom to blot out the stain, and their dialogue shifted into sly innuendo. Margot suggested it might be easier if Maxine removed her dress entirely; Maxine, without missing a beat, teased back that she knew Margot had other ideas.

Ink and watercolor, mid-century fashion mode

Here, Maxine stands in crimson, Margot leaning toward her in ivory — the color contrast heightening the tension between confidence and vulnerability. The drink in Maxine’s hand recalls cocktail-hour glamour, yet her posture conveys command, not passivity. It is an image that crystallizes power, poise, and the shifting gender dynamics of mid-century theatre reimagined.

What might once have been played as a polite aside was reframed here as flirtation, as intimacy hidden in plain sight. The stain became pretext, the dress became subtext, and the bourbon-spill moment crystallized the electric charge between the two women — a reminder that suspense lives not just in murder plots, but in glances, gestures, and the words left hanging in the air.

Ink and wash with domestic detail

Tony’s voyeuristic gaze through the window reframes his jealousy as obsession. Inside, Maxine and Margot’s kiss radiates warmth and defiance, grounded by the mundane presence of spaghetti on the table. This juxtaposition — intimacy versus intrusion, love versus control — sharpens the play’s psychological edge.

Another telling moment came when Tony confided to Lesgate about spying on Margot. He revealed that she had gone to Maxine’s flat, and that he had once caught them in each other’s arms — a disclosure that reframed Tony’s jealousy not just as a husband’s suspicion, but as a twisted obsession with control. What might have been played as casual backstory in other productions became a pointed reminder: Tony’s cruelty was sharpened by the knowledge of Margot’s real love. The break, he said, came after a spaghetti dinner — an oddly domestic detail that made their intimacy feel all the more real.

Archival Note: When Dial M for Murder first appeared in 1952 (and in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 film with Grace Kelly), women’s agency was minimized, their desires made scandalous. In both Knott’s original text and Hitchcock’s film, Margot was written as having an affair with a man. Seen in 2025 — a year where representation is under sharper focus — this staging feels like reclamation. It honors the mechanics of the original thriller, but lets women (rightfully) own the story in a way the mid-century never allowed.

The Cast Connections

Ink and wash, group tableau

The production’s repertory depth is embodied in this tableau: Tony, Inspector Hubbard, Margot, and Maxine together in a single frame. Familiar faces reappear in new guises, underscoring the continuity of regional theatre. The women, however, command the eye — their presence reframing the narrative’s center of gravity.

One of the joys of regional repertory theatre is watching familiar faces return in new guises. This production drew richness from precisely that shared history — the actors carried with them echoes of past roles, creating layers of recognition and reinvention that made this staging of Dial M for Murder feel both freshly alive and firmly rooted in tradition.

Tom Walton (Tony Wendice) and Mark Schwahn (Inspector Hubbard) had just played Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, M.D. in Clackamas Repertory’s season opener, Sherlock Holmes and the Precarious Position — a play also set in London, written by Margaret Raether.

Digital oil study after Victorian portraiture, 2025

Here Holmes and Watson are rendered with painterly gravity, their silhouettes emerging from the gaslit haze of London streets. The image evokes academic portraiture — the solemn tradition of Victorian moral drama — yet its placement within the archive is sly. These same actors, seen moments before in comic pandemonium, are reframed as icons of seriousness and atmosphere. The juxtaposition with farce highlights repertory as an art of transformation: one season, one company, conjuring entirely different worlds through the same faces.

Earlier this same year, Walton and Schwahn also appeared together in the farce Noises Off for Lakewood Theater Company, with Walton as Gary Lejeune and Schwahn as Frederick Fellowes. That continuity made the production feel like an inversion: Watson investigating Holmes gone astray — loyalty giving way to betrayal.

Ariel Puls (Margot Wendice) brought incredible complexity to the role of Margot, a wealthy woman torn between her dull, respectable marriage with Tom (maintained to please a deceased, unmarried rich aunt) and her deep, true feelings for Maxine in a world not open to two women being lovers.

That complexity immediately drew the audience’s sympathy. Puls, a Portland, Oregon native who describes herself on her website (as of 2025) as “an avid Shakespeare fan” with her acting “rooted in classical theatre, movement-informed performance, and new play development,” also appeared in Noises Off as Poppy Norton-Taylor, sharing the stage once again with Walton and Schwahn.

Ink and wash illustration, anonymous digital atelier, 2025

This whimsical sketch reimagines Sherlock Holmes not in the fog of Baker Street but in the manic corridors of farce. The stage manager — headset, clipboard, perpetual motion — becomes the unseen heroine of repertory theatre, chasing after mysteries with the same urgency she wrangles missed cues and misplaced trousers. Its style deliberately echoes mid-century caricature posters, situating the players in a world of constant entrances and exits. Within the archive, the image functions as connective tissue: a reminder that actors pivoting from chaos to suspense embody the repertory’s multiverse of roles.

Seeing Puls, Walton, and Schwahn pivot from the comic chaos of farce to the taut suspense of a thriller highlighted the range and adaptability that define regional theatre. The shift — from doors slamming and trousers dropping to blackmail and betrayal — felt like a repertory multiverse in motion, farce reconfigured as thriller. For audiences tracking both companies, it became more than connective tissue; it was a reminder of repertory’s greatest gift: that one door always leads to another — sometimes to laughter, sometimes to danger.

Kelsey Glasser (Maxine Hadley) brought her own distinction. Not only is she a gifted actor, but offstage she is a Portland, Oregon sommelier, host of Her Way, a podcast featuring interviews with women in the wine industry, and the owner of Arden, a wine-focused restaurant in downtown Portland. That blend of artistry — theatre and hospitality — lent Glasser’s Maxine a worldly sophistication, making the character feel lived-in, confident, and grounded.

Archival Note: Glasser’s dual presence in both the performing arts and Portland’s hospitality scene situates Maxine not only as a character within the play, but as part of the city’s living cultural fabric.

These casting echoes didn’t overshadow the story; they enriched it. For those who’ve followed Oregon theatre, the crossovers and hidden layers made Dial M for Murder feel at once a self-contained drama and part of a larger cultural fabric.

Why It Belongs in the Archive

Fashion sketch, imagined rehearsal for Dial M for Murder

Here, the composition shifts from performance to process. A woman director — drawn in crisp slacks, glasses, and scarf — gestures with authority, sketch pencil still in hand. Before her, Margot and Maxine sit together, whiskey glasses poised, their attention not on the script’s treacheries but on her vision.

The illustration reframes Dial M not as a thriller of male orchestration but as a production sculpted by women’s voices. The staging hand is female; the story belongs to its actresses. What might have been rendered as spectacle becomes a rehearsal of power — collaboration, listening, trust.

The sepia-washed palette grounds the image in mid-century style, yet its insistence on showing the woman director at work underscores a contemporary truth: theatre, like this sketch, is made as much in the hands of women as in their portrayals.

Taken together, this production was more than a clever revival. It was a story owned by women, guided by a woman’s hand, and framed by theatrical continuities that made the performance feel like part of a living repertory. That combination makes it not only memorable, but indispensable to preserve.

This production offered a triple: repertory echoes (Holmes/Watson fractured into Tony/Hubbard, cast carried over from Noises Off), thematic inversions (farce into thriller, loyalty into betrayal), and feminist reclamation (Margot and Maxine’s kiss, their love acknowledged).

Even the coats by the door — Maxine’s black, Margot’s cream — stood as proof of their bond. A moment too rich to fade.

What made this production unforgettable wasn’t the murder or the clever mechanics, but the way Margot and Maxine carried the heart of the story. That is why it belongs in my archive.

Some productions leave you entertained; others leave you with memories worth preserving. This one left me with both — and a record worth archiving.

Archival Meta Note: I’m not a professional archivist, but I approach these productions with an archivist’s care. These notes are my way of preserving not only what I saw on stage, but why it mattered — as memory, as culture, and as a record of care. In that choice, the archive becomes not just a record of art, but a record of care.

You must be logged in to post a comment.