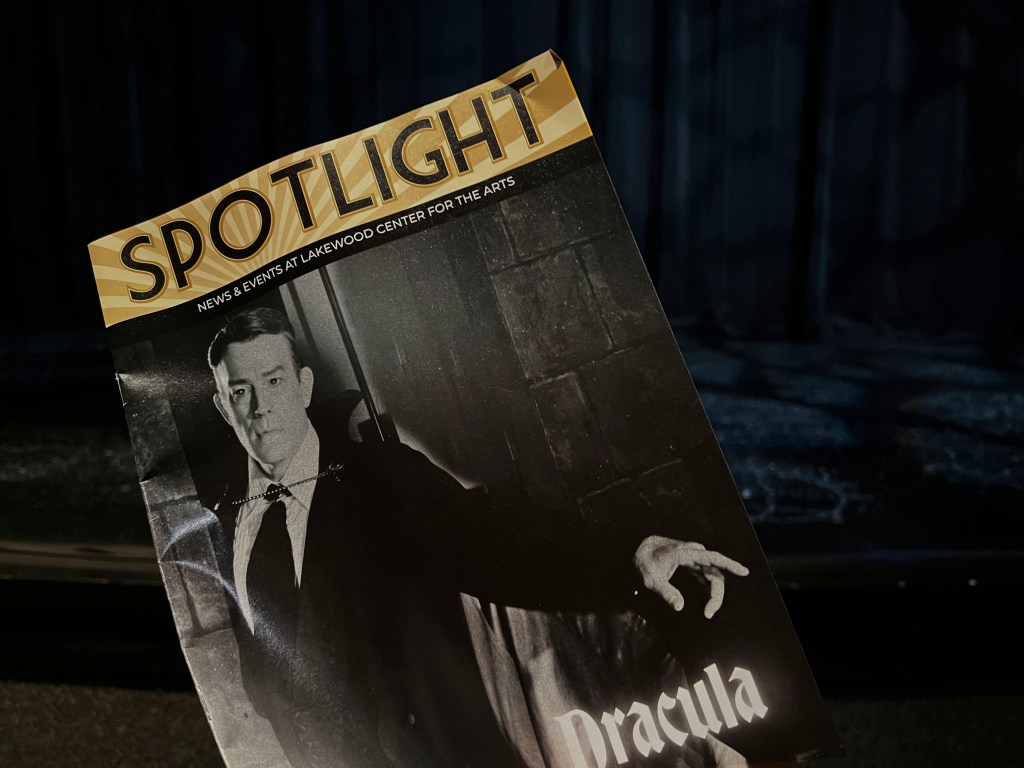

Dracula

Lakewood Theatre Company — October 4th, 2025

Headlee Mainstage, Lake Oswego, Oregon

Directed by Mark Pierce

Adapted by Hamilton Deane & John L. Balderston

Based on the novel by Bram Stoker

Notes from a Saturday matinee where Gothic menace meets repertory tradition.

Prelude: Entering the Theatre

Every performance begins long before the curtain rises. It begins at the threshold — the moment a ticket is exchanged for anticipation.

I’ve been to Lakewood Theatre in Lake Oswego, Oregon many times, but the box office never loses its charm. Warm wood, golden light, and that familiar hush before a show.

For Dracula, even the lobby felt like a prologue — paper bats hovering above the ticket window, red velvet lining the corridors, the air charged with something theatrical and ancestral.

Before a word was spoken, Dracula had already arrived.

Now, in its 73rd year, Lakewood Theatre’s 2025 revival doesn’t attempt to modernize him — it excavates him.

What emerges is not nostalgia, but endurance: the Gothic reimagined as ritual, performed once more for a world that still feels his shadow.

Archival Footnote: According to Lakewood Theatre’s Past Shows Archive, the last time the vampire rose on this stage was nearly half a century ago — in 1976, for a production of Count Dracula.

That forty-nine-year gap makes the 2025 revival not just another staging, but a resurrection. A return of the Gothic to Lake Oswego’s boards — not as nostalgia, but as ritual continuity.

First Impressions

Theatre begins before the lights dim — in the walk from lobby to seat, in the quiet anticipation that turns an ordinary Saturday afternoon into ritual.

The approach to Lakewood’s Headlee Mainstage — the same entrance I walked through back in March for Noises Off — already felt like an initiation. The familiar red velvet curtains flanked the corridor, while a constellation of more paper bats circled overhead — a playful omen of what waited beyond.

Before the Curtain

In the lobby, a coffin overflowed with florals, ivy, and dried leaves — part shrine, part installation. It was not macabre so much as mournful: a tableau of life’s decay dressed for theater.

It wasn’t kitsch. It was prophecy.

Inside, the stage was sealed behind a black curtain, its surface patterned by a lattice of spectral light — like moonlight trapped in a spider’s web.Pre-Curtain Music

Pre-Curtain Announcement

Even Professor Van Helsing’s voice served as the house announcement — a prelude warning of “immortality and bloodlust,” and of “gentle acts of seduction and fear.”

It was both warning and invitation, the line between theater and invocation deliberately blurred. By the time the lights dimmed, we were already under Dracula’s influence — transfixed before the curtain had even risen.

Why This Production Stands Out

A World Drained of Color

The production unfolded within three confined spaces — the library of Dr. Seward’s sanatorium, Lucy’s boudoir, and a brief, spectral vault in Act III. Each set was rendered in tonal austerity, as if carved from fog and memory.

What Lakewood’s Dracula achieved visually was less design than invocation: a monochrome world that looked as though it had stepped from a nitrate reel — a living black-and-white film where time itself had been leached away.

This was not the absence of color but the mastery of it. The palette obeyed a rigor usually reserved for restoration labs and curators — color rationed like breath, held back until it could wound.

The Color Red

Red appeared only by permission. It was never background, never decoration — only revelation.

A crimson medical bag in Van Helsing’s steady hand.

Lucy’s tightly wound red scarf, a premonition in fabric.

The dark gleam of wine shared by men who mistook ritual for reason.

By the second act, the red had migrated — Miss Wells’s apron, Renfield’s suspenders, the faint lining of a cape. Color as contagion. Color as pulse.

And then, in Act III, the quiet rupture. Lucy’s handkerchief, passed from trembling fingers to Van Helsing’s grasp — returned red.

No scream. No visible wound. Just implication, the stagecraft of omission doing what spectacle never could.

Even the script itself played with the idea of what color means. When Dr. Seward offered Dracula a glass of wine in Act I, the Count declined with quiet precision:

“I do not drink… wine.”

The pause hung in the air like a shadow.

The audience chuckled — but softly, knowingly — aware they were witnessing one of horror’s most enduring lines.

It wasn’t parody. It was preservation — a single phrase carrying ninety years of cinematic bloodline.

In that moment, the production achieved something archival in its precision: horror not preserved through gore, but through restraint. A single chromatic memory, recorded on the mind’s film, impossible to fade.

Lucy Seward

Lucy Seward (played by Kylie Jenifer Rose) became the emotional center of Lakewood’s Dracula. She wasn’t the swooning ingénue of early cinema, nor the helpless Gothic victim. Her descent — if one can call it that — felt less like corruption and more like possession.

Her early dialogue with Van Helsing set the tone for everything to follow. When asked when her weakness began, Lucy recalls softly:

“Two nights after poor Mina was buried, I had a bad dream. I remember hearing dogs barking before I went to sleep… the air seemed oppressive. I left my reading lamp lit by my bed, but when the dream came, there seemed to come a mist in the room.”

– Dracula (Act I)

The line landed with eerie precision — not just as confession, but as premonition. Rose delivered it as though Lucy were already half-remembering her own disappearance, her voice caught between waking and nightmare.

This Lucy wasn’t merely preyed upon; she was absorbed into a system of control — by Dracula. Every attempt to “save” her felt like another form of confinement.

By Act III, when Van Helsing pressed the crucifix to her throat, her recoil wasn’t fear — it was exhaustion. A woman prayed over, diagnosed, and examined until even her body’s surrender was no longer her own.

In that stillness, Dracula stopped being about the monster in the room and became about the quiet horror of possession — spiritual, physical, and social — that women have known for centuries.

Count Dracula Himself

In Lakewood’s 2025 production, Count Dracula (Leif Norby) emerges as a 21st-century, #MeToo-era reflection on power — a study of charismatic yet manipulative men who wield charm as control. This Dracula retains the suave, aristocratic diction and bearing inspired by Bela Lugosi, yet his movements are sharper, more predatory, more deliberate in how he occupies space.

One scene in particular defines the production’s menace: Dracula seduces Miss Wells (Brenna Warren), the maid, in Lucy’s boudoir — a moment of chilling psychological dominance in which he promises relief only through surrender.

“What is given, can be taken away. From now on, you have no pain and no will of your own.”

– Dracula (Act II)

Later in the act, under his gaze, Miss Wells removes the wolfbane necklace and cross that Van Helsing placed on Lucy to guard her during sleep — granting Dracula literal and symbolic access to his victim.

“When I order you to do a thing, it shall be done.”

– Dracula (Act II)

Viewed through the lens of American cultural history, the moment carries an unnerving echo — not of a single event, but of a broader truth: how charisma, devotion, and control can become instruments of ruin. The atmosphere of ritualized obedience recalls moments when charm and ideology blurred into manipulation, when the performance of devotion concealed the machinery of domination.

It’s also worth noting that Dracula isn’t Norby’s only brush with villainy this year. In August 2025, Norby portrayed Mr. Applegate — the Faustian tempter in the baseball musical Damn Yankees for Clackamas Repertory Theatre in Oregon City, Oregon. From baseball diamonds to blood-soaked boudoirs, Norby’s performances seem to trace a single, seductive archetype: the smiling face of damnation.

The Long History of Draculas

When tracing the history of Count Dracula, Bela Lugosi’s stage and 1931 film performances didn’t merely redefine the vampire — they transformed him into an enduring cultural archetype. Lugosi’s suave menace revolutionized how audiences imagined horror itself, opening the floodgates to countless imitations, adaptations, and parodies across film, television, theater, and beyond.

Dracula became more than a monster; he became mythology. By the mid-20th century, his cape and accent were shorthand for Halloween itself — inspiring everything from serious revivals to breakfast-table caricatures. (Count Chocula, anyone?)

And it didn’t stop with adults.

Children’s media quickly embraced the vampire with playful irony: Sesame Street’s numerically obsessed Count von Count, Cosgrove Hall’s 1980s British vegetarian duck vampire Count Duckula, and even Garfield & Friends’ “Count Lasagna,” where Garfield the Cat seeks pasta cravings and marinara sauce. Each parody softened the bite while keeping the charm — proof that Lugosi’s legacy had truly sunk its teeth into every corner of pop culture.

Despite Dracula’s place in pop culture, it’s the origin story that shows the richness of why Dracula has endured for so long.

Fortunately, an 8-minute TED-Ed video narrated by Stanley Stepanic (embedded below), “How did Dracula become the world’s most famous vampire?” had the answers.

Through parody and homage alike, Dracula survives — not as relic, but as ritual — a story retold to remind us that the shadows never really leave.

Archival Note: When Dracula first haunted the stage in the 1920s, it captured anxieties about modernity, sexuality, and foreignness. Seen in 2025, the Gothic feels less about fear of the outsider and more about who controls desire, faith, and the body.

Behind the Production

Notably, Dracula at Lakewood featured a diverse and talented creative team whose work shaped the show’s haunting precision.

Elizabeth Young’s sound and dialect design gave voice to the play’s Gothic pulse.

Sam J. Holden (she/they) served as intimacy director, ensuring the production’s moments of seduction and fear were rendered with nuance and safety.

Devon Wells (they/them), with a background of animation and illustration, designed the hair and makeup, crafting a visual world where shadow and ritual beauty became part of the storytelling itself.

Their combined artistry lent the production its equilibrium — tension and empathy, restraint and revelation — proof that even in a narrative long centered on male dominance, it is women and non-binary creators who now shape its atmosphere of control, vulnerability, and care.

Why It Belongs in the Archive

Because Dracula endures — not through spectacle, but through suggestion.

Lakewood Theater’s 2025 production understood that the Gothic lives not in excess, but in what’s withheld. The color red meant more precisely because it was rare. The bite terrified more because it was unseen.

This adaptation — faithful to its 1927 stage roots — carries within it a conversation about power that feels distinctly modern. The women in the story are neither merely victims nor tropes; they are witnesses to the machinery of manipulation, trapped in rooms that echo the very structures the play critiques.

To watch Dracula in 2025 is to confront how easily charisma becomes control, and how beauty can mask domination. It’s not nostalgia — it’s reflection. That is why this production belongs in the archive: not because it resurrected an old legend, but because it held a mirror to the one still haunting us.

I look forward to returning to Lakewood Theatre next year for the upcoming season — to see what other ghosts the stage might wake.

Archival Meta Note: I’m not a professional archivist, but I approach these productions with an archivist’s care. These notes are my way of preserving not only what I saw on stage, but why it mattered — as memory, as culture, and as a record of care. In that choice, the archive becomes not just a record of art, but a record of care.

You must be logged in to post a comment.