Dracula

Oregon Ballet Theatre — October 11th, 2025

Keller Auditorium, Portland, Oregon

Staged by Dominic Walsh

Choreography by Ben Stevenson, O.B.E.

Stage Manager: Jamie Lynne Simons

Music by Franz Liszt, in an arrangement by John Lanchbery,

Seattlemusic Orchestra conducted by Ermanno Florio

Notes from a Saturday matinee, when some stories cannot be spoken — they must be felt, carried through shadow and light.

Archival Preface: The Dance of Shadows: Ballet strips the myth to its bones: desire, surrender, immortality, and the choreography between them. Where the “Dracula” play offered wit and dialogue, the ballet offers breath and silence — gestures that flicker like candlelight across the stage.

I write this not as a critic, but as an archivist of atmosphere — preserving how a myth moved, literally, through the body.

A Matinee of Velvet and Whispers

On a calm, overcast Saturday afternoon, I made my way to Keller Auditorium in downtown Portland for Dracula.

Wearing my red coat — and passing the haunting ballet poster fluttering near the trees — I stepped inside the lobby.

The Playbill

Tucked off to the side, away from the flow of arriving patrons, I opened the Dracula playbill. A letter from Artistic Director Dani Rowe immediately caught my attention.

Rowe stated in her letter the Dracula ballet “blends classical technique with sweeping theatricality—ornate sets, hauntingly beautiful costumes, and a score that chills and enchants in equal measure.”

I already couldn’t wait for the curtain to rise — and I hadn’t even made it to Performance Perspectives yet.

Inside the Ritual: Company Class

Before Count Dracula rose from the shadows, the dancers of Oregon Ballet Theatre revealed something even more extraordinary — the discipline beneath the drama.

The transformation began not with fangs or fog, but with muscle, repetition, and music.

Before Performance Perspectives, a pre-show event led by OBT historian Melanie Summers, I had the rare chance to witness company class unfold live onstage. It was a glimpse not into performance, but into preparation — that quiet, exacting magic that happens before the spotlight ever finds them.

Summers guided us through what unfolded as the dancers completed their company class: an hour-long warm-up of jumps, turns, and precise muscle memory.

“This is a great opportunity to sit in the front row without paying front-row prices,” she joked, as Chase Davis led the session, accompanied by a live pianist. The air hummed with piano notes and the soft percussion of slippers striking wood.

“They’ve been in class for over an hour,” Summers explained, “preparing their bodies to handle the immense amount of jumping and traveling ahead.”

The dancers—still in their warm-up gear, not yet cloaked in character—rehearsed challenging combinations across the marley-covered stage, their pirouettes punctuated by the live pianist in the corner. Summers noted the stage floor’s responsiveness to humidity, the presence of dry-ice fog (which subtly slicks the surface), and the necessity of recalibrating choreography to the technical variables of the venue.

“It’s not just about warming up the muscles — it’s also about waking up the brain. Fast-twitch memory. Split-second recall. It’s a testament to how smart dancers are.”

Summers pointed out how dancers “learn an entirely new combination every 30 to 60 seconds,” how they train both body and brain, and how even the stage itself is built to give, absorbing impact so the dancers’ landings remain “quiet, safe, and ethereal.”

And what a view it was: a line of dancers moving from upstage to downstage, training for the grand allegro — larger jumps and traveling phrases that demand both power and control.

There was laughter when she noted the instructor’s Vlad the Impaler shirt, a perfect wink to the evening’s theme. Then came the quieter insights — pointe shoes “banged against the floor” backstage to dull their noise, the final port de bras of the class where dancers bowed to imaginary applause.

“They’re taking a moment to breathe and soak it all in,” Summers said softly, as the company mirrored their teacher’s gestures.

What struck me most was the intimacy of it all — the dancers weren’t performing yet, but they were sharing something more vulnerable. The scaffolding behind the spectacle. The breath before the bite. It felt less like a warm-up and more like a ritual — a private language of discipline and grace before the darkness of Dracula descended.

They weren’t performing yet – but already, the spell was forming.

Performance Perspectives:

The Calm Before the Curtain

After the dancers left the stage and the curtains descended, the theater took on a quiet expectancy — not the hush before lights-down, but the kind of pause that happens between rehearsal and transformation. The stagehands were preparing the world of Dracula behind the curtains, but out front, the house lights remained up.

A projection screen unfurled from above like a modern curtain call, and Melanie Summers stepped into the light — part historian, part storyteller.

Summers’ commentary was too fascinating not to share in full — equal parts backstage tour and theatrical storytelling. Her words, excerpted below, brought the stagecraft to life before a single dancer took the stage.

It was informal, lively, and brimming with the kind of detail that only deep familiarity can produce. She called it “a behind-the-scenes and historical prelude,” and it truly was — a bridge between backstage chaos and audience wonder.

Summers explained how the dancers had just left to begin the full metamorphosis into character — the brides applying ghostly makeup, the village peasants readying their bright costumes, the fog machines and set pieces being tested behind the curtain.

Then she began to trace the production’s lineage: choreographer Ben Stevenson’s 1997 premiere, the Liszt-based score arranged by John Lanchbery, and the meticulous re-staging under Dominic Walsh, a former principal with Houston Ballet who once danced Frederick himself.

She then guided us through the visual language of the production: over 70 costumes—borrowed from Texas Ballet Theatre—bringing to life the folkloric vibrancy of village life and the ghostly severity of Dracula’s castle. Scenic Designer Thomas Boyd‘s sets borrowed inspiration from medieval woodcuts and German expressionist cinema, while Tony Tucci‘s lighting etched shadow and flame in equal measure. Blood-red cloaks, flickering candles, a trembling chandelier—this was ballet as a haunted painting.

The technical trivia was the most delightful part — the weight of Dracula’s 30-pound cape, the fiberglass rods that give it a 23-foot wingspan, the hidden bat design stitched into the back.

Dancers Pulling Double Duty

The dancers’ transformations were as physical as they were visual.

The Brides doubled as village peasants in Act II, then returned veiled and hovering in Acts I and III, adorned with ornate wigs and pallid makeup.

“A lot of the dancers are doing double duty, multiple different roles, lots of crazy, fast costume and makeup changes. It is absolute controlled chaos back there.”

She joked about how she kept asking the brides if they felt alright:

“The dancers that play brides, many of them are also the peasants in act two. And so they have to go from full bridal makeup. And I’ve been annoying them to death by walking up to the brides and saying, ‘Hey, you look a little pale. Are you okay? Are you feeling okay?’ And some of them take me seriously. They’re like, ‘what’s wrong?’ I’m like, ‘it’s the makeup.’“

And hilariously, skincare routine entered the talk from Summers:

“I’m going to try to nail some of them down to see what their skincare routine is, because putting on that crazy theater makeup, taking it off and putting it right back on, especially today, they’re going to have to do it twice because today’s the matinee.”

Performance Perspectives: The Art and Physics of Dracula in Flight

When Summers reached the topic of flying effects, guided by the team at ZFX, the room buzzed with quiet amazement.

Even the flying, she explained, was a feat of precision and sweat — especially in Dracula’s case, which almost plays out like a complicated video game in stage form.

“The machine that controls the flying is both manual and automatic. They have automations like when Dracula flies in, there’s actually somebody that’s running like a drone style computer with a joystick on it to bring him up and down.“

The Brides, meanwhile, relied on old-fashioned counterweights and rigging — suspended, yes, but not untethered from effort.

“When you see the brides flying back and forth, there are two brides that fly back and forth. One person’s doing this side, one person’s doing this side and then they switch and it is just, it’s just amazing. It’s remarkable. And by the time the riggers are done, they are so out of breath.”

When it comes to Flora’s moment of flight, the behind-the-scenes magic is spectacular, as Summers said in her own words:

“There is a scene at the end of act three where Flora is flying up into Dracula’s bedchamber and she comes back and forth a couple of times and she goes very quickly. And the way that this is done is by sheer woman power. There is a rigger back there who stands on the sixth rung of a ladder and she pulls as hard as she can and she jumps down and then somebody else grabs on top and they just yank that sucker as hard as they can to make Flora go flying across the stage.”

Summers also pointed out that none of these sequences can be fully rehearsed until the company moves into the theater, making each performance a feat of timing, coordination, and invisible precision that somehow appears effortless from the audience’s view.

When you think about it, it’s one thing to rehearse in the spacious safety of a ballet studio. But on the Keller Auditorium stage — where large-scale Broadway tours perform year-round for nearly 3,000 people a night — the stakes shift. The sight lines change. So do the spacing, the cues, the timing, as Summers noted:

“Whenever there’s a fight scene or a flight scene in a ballet, those are practiced right before the act that they occur again, just to make sure because it’s a necessity of safety and all the different things.”

By the end, Summers had not only demystified the performance but deepened it — connecting Bram Stoker’s 1897 imagination to the ballet’s theatrical alchemy.

“You’re about to see towering sets, fog, and even an exploding chandelier. What happens next is art, but also controlled chaos — a miracle we get to witness twice today.”

When the screen lifted and the house began to fill, the magic felt ready.

The lecture lights still glowed, but behind the curtain, the shadows were stirring.

The Language of Partnership:

“Pas de Deux“

As Dani Rowe also stated in her letter, with this ballet, “One moment you’ll see a pas de deux as tender as any in the classical canon; the next you’ll be swept into the terror of Dracula’s dark world. It is a ballet at its most cinematic: lavish, emotional, larger than life.”

In classical ballet, the pas de deux — literally “step of two” — is the art form’s heartbeat of connection. It’s a duet between two dancers, traditionally structured in four parts: the adagio (a slow, lyrical opening), two variations that showcase individual technique, and a coda that reunites the pair in a flourish of shared virtuosity.

There’s a theatrical kinship here with ballet’s most iconic deception — the Black Swan pas de deux from Tchaikos Swan Lake — though in Dracula, the stakes are not mistaken identity, but blood, death, and eternal hunger. Every lift becomes both devotion and danger — a dance between Svetlana’s freedom and Dracula’s possession.

In some ways, even the most spooky pas de deux hasn’t been limited to ballet, it’s even inspired the world of film music in unique ways. Like Pulitzer-Prize winning American composer Michael Abels composing a menacing, staccato-like score, “Pas De Deux” for Oscar-winning filmmaker Jordan Peele’s 2019 horror film, Us, which you can listen here.

In Dracula, these moments take on a darker pulse. The familiar beauty of the pas de deux — trust, balance, surrender — becomes a metaphor for control and temptation. In Act II, the romantic duet between Svetlana and Frederick in the village still glows with youthful purity, but by Act III, that same choreography is shadowed by Dracula’s influence. Every lift becomes both devotion and danger — a dance between freedom and possession.

Transported To Transylvania

With the Performance Perspective concluded, I took my seat in Orchestra A, Aisle 2, Row G, Seat 10 ready to be transported from the real world to the world of Transylvania.

A day before Dracula opened, Oregon Ballet Theatre released a trailer showing highlights from the 2022 production, which I had watched multiple times the night before to prepare for the world I was about to be swept in for two hours.

What follows are archival-style visual recreations and written impressions of each act.

🎨 Visual Notes

Inspired by the ballet’s haunting stagecraft and the legacy of Expressionist cinema, all accompanying images follow an Expressionist Noir Ballet style — blending shadow play, motion, and myth.

Act I – The Crypt of Dracula’s Castle

A chiaroscuro expressionist painting captures Dracula’s lair — shadowy, Gothic, and haunted by veiled brides. Flora is shown crumpled, ghostlike, as the Brides close in like a ritual of possession.

(Visual interpretation — archival recreation in expressionist noir style)

The curtain rose into smoke and shadow. We were in the crypt — a cavernous space haunted by Dracula’s Brides, who moved like forgotten memories brought back to life. Their sharp, deliberate choreography was eerie and beautiful, and then Dracula (performed by Isaac Lee) himself emerged, cloaked in power and silence.

Then Flora (performed by Zuzu Metzler) was dragged in by Renfield (performed by Giovanny Garibay) — Dracula’s mad scientist, as agile and unhinged as a Cirque du Soleil performer — and the mood shifted from eerie to tragic. She wasn’t just another victim — she was offered like a gift to darkness.

That final image of her, caught between worlds, stayed with me long after the act ended. Especially during the first 20-minute intermission of the show.

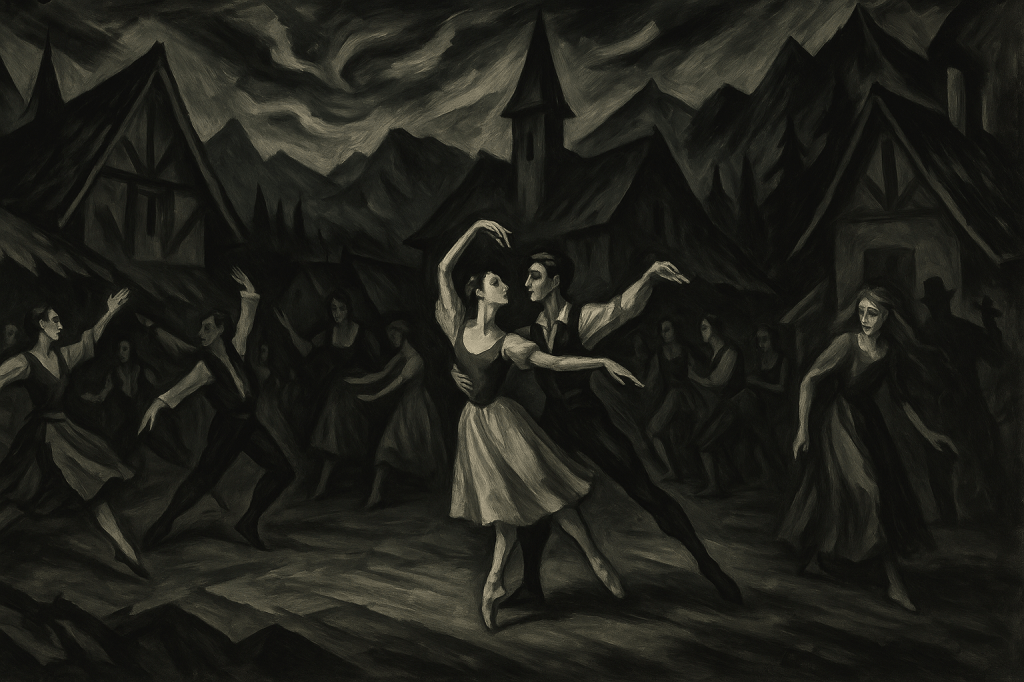

Act II – The Village

A stylized stage painting shows a joyous pas de deux between Svetlana and Frederick. Villagers dance in Eastern European costumes, but in the shadows, Flora appears ghostly and displaced, foreshadowing the storm to come.

(Visual interpretation — archival recreation in expressionist noir style)

The Carpathian village burst with light and laughter — dancing feet, clinking mugs, the priest’s (played by James Johnson) hand raised in blessing. But not all joined in. At the edge of the revelry stood an old woman (performed by Ruby Mae Lefebvre) with a necklace of garlic, her eyes fixed on the distant castle no one dared name.

Svetlana (performed by Kangmi Kim) and Frederick’s (played by Bailey Shaw) love felt tender and sincere — their pas de deux full of youthful warmth, even as the innkeeper mother (performed by Hannah Davis) blessed them with approval and the inkeeper father (performed by Brian Simcoe) eyed them with the kind of patriarchal caution that only softened when promises of future children were made.

Even from the orchestra level, you could feel the joy — vibrant and infectious, if occasionally hemmed in by tradition — as if we’d stepped into a different ballet altogether.

But beneath the celebration, unease crept in. The old woman gave Svetlana a necklace of garlic and pointed toward the looming silhouette of Count Dracula’s castle. Her warning lingered.

Then Flora stumbled into the village — pale, marked, and wrong — and everything shifted. Her attack on the villagers sent a rupture through the revelry. Joy cracked like glass. The priest, trembling but resolute, raised his crucifix in a desperate attempt to ward off the evil that had taken hold — of Flora, of Dracula, of the night itself.

Dracula’s arrival — flanked by Renfield and the black coach — crashed down like a storm splitting the sky. While Flora ripped the garlic necklace away from Svetlana.

He didn’t just abduct Svetlana. He shattered the world we’d just been welcomed into.

And with that, the curtain fell again — another twenty-minute intermission, with shadows trailing behind it.

Featured Dancer:

Kangmi Kim as Svetlana

The role of Svetlana for the matinee performances were danced by Kangmi Kim, a company artist with Oregon Ballet Theatre who joined in 2021 after apprenticing since 2019. Originally from Seoul, South Korea, Kim brought a striking emotional clarity to Svetlana’s journey — from innocence in the village to haunted resolve in Dracula’s lair. Her incredible pas de deux moments shimmered with both vulnerability and strength, especially in the ballet’s final act, where each gesture felt like both a memory and a warning.

Act III – The Bedroom of Count Dracula

A monochromatic Expressionist-style painting captures the final act’s climactic pas de deux. Svetlana, now in a flowing bridal gown, confronts Dracula in a moment of haunting intimacy and resistance. Around them, the fallen chandelier, ghostly Brides, and shadowed villagers echo the chaos and loss of the preceding battle. Theatrical lighting slices through the gloom like a final blessing — or a blade of dawn.

(Visual interpretation — archival recreation in expressionist noir style)

This final act felt like a fever dream. The Brides hovered. Svetlana reappeared in a bridal gown. The set was all flickering light and looming threat. Dracula moved with terrifying stillness — every gesture controlled, every lift like a predator claiming its prize.

The final moments were breathless. Flora’s flight. The fight between Dracula, Reinfield and the Brides against Frederick, the innkeeper father, the priest, and several men from the village. The chandelier. The flood of daylight. And then, that quiet, tender pas de deux between Frederick and Svetlana — after everything. It was fragile and solemn, not triumphant. A kind of love touched by grief.

One

And then, the performers took their bows to roaring applause and cheers.

Closing

What Dracula left behind was more than a tale of horror or romance — it was the sensation of movement suspended in shadow, of myth embodied and then vanished.

As Dani Rowe so perfectly phrased it: “It is not just a performance — it’s an immersion.”

As the lights dimmed and the audience rose, I wasn’t walking away from a story. I was carrying it — in breath, in stillness, in the echo of bodies that danced darkness into something unforgettable.

Making my way out of Keller Auditorium for the treak home, I snapped a photo of the poster that would later that night would become one of my favorite documented photos so far: spectral and seasonal, as if spirits lingered just behind the glass.

Archival Note: I do not claim the title of professional archivist, but I write with an archivist’s intention. These notes preserve more than what was staged — they preserve what stayed.

Earlier that morning, I stood before another kind of stage — the portrait of Infanta María Ana de Austria at the Portland Art Museum. Read that reflection here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.