When you think “feminist film icon,” Miss Pinkerton probably isn’t the first movie that comes to mind. It’s a 1932 mystery-thriller starring Joan Blondell, and to be fair, it wasn’t exactly marketed as a proto-feminist statement. Sure, it came out during Hollywood’s Pre-Code era—when liberated, independent women were having their moment on screen—but this one? It’s based on the novel Miss Pinkerton by Mary Roberts Rinehart, co-written for the screen by Lillie Hayward… yet directed by a man and pitched as a spooky whodunit, complete with shadowy mansions and plenty of suspicious glances.

But if you watch it today (or rewatch it) through a modern lens, you’ll notice something interesting hiding beneath all the crime-solving and old-school charm.

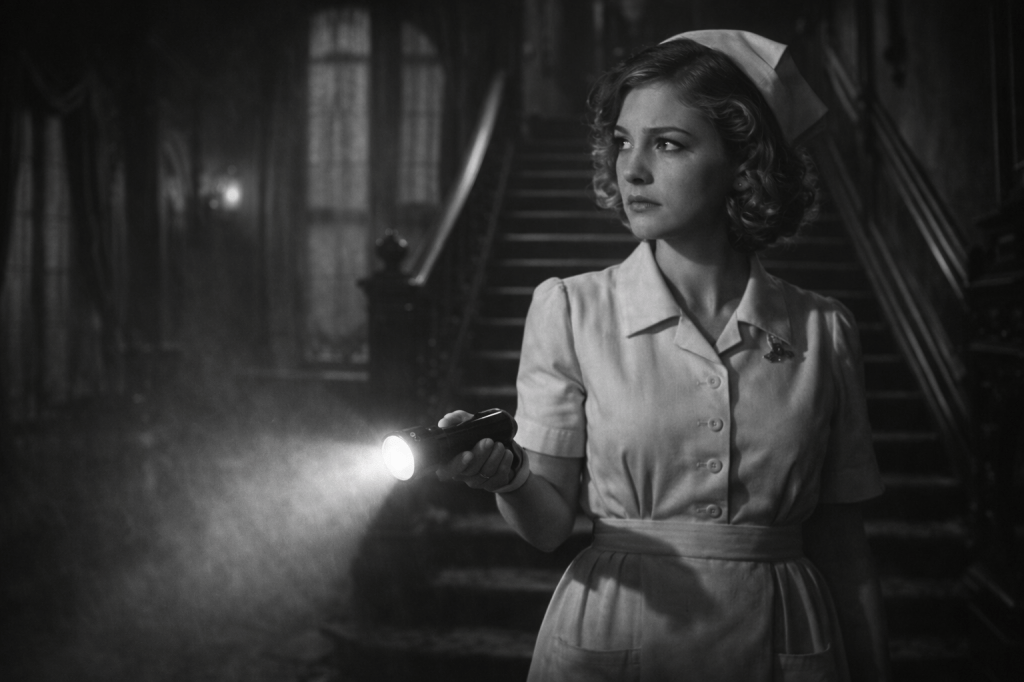

Joan Blondell’s character, Nurse Adams, aka “Miss Pinkerton,” sneaks in some serious feminist vibes—without making a big speech about it. She’s working. She’s independent. And she’s the one figuring things out while the men puff their pipes and scratch their heads.

Here’s why this 1930s murder mystery feels surprisingly ahead of its time.

She’s a Working Woman

with Agency (and She’s Good at It)

Let’s start here. Blondell’s Nurse Adams is called in to care for an elderly woman in a gloomy old house after a suspicious death. Classic setup. But unlike a lot of early 1930s films where the female lead is there to faint gracefully or scream at the right time, Adams isn’t just background noise. She’s a professional. She’s competent. She knows how to handle herself in a crisis.

And when the situation starts getting weird—murder weird—she doesn’t wait around for a man to tell her what to do. She takes the initiative. She investigates. She pokes her nose where everyone tells her not to. She runs toward the mystery. Imagine that: a woman who gets paid for her skills and uses them to her advantage. Revolutionary stuff for the era.

She Trusts Her Instincts—

Even When the Men Don’t

There are a few classic “there, there, little lady” moments sprinkled throughout Miss Pinkerton. (It’s 1932. We were bound to hit one or two.) The cops and various menfolk are quick to brush her off. But instead of taking that as her cue to retreat quietly into the background, Adams does the opposite. She doubles down on what she believes is right.

She trusts her gut when others dismiss her, and surprise! She’s usually right. Watching her navigate a world full of condescension with her head held high is incredibly satisfying. And if that’s not a mood for women everywhere, I don’t know what is.

She’s Smart and Witty

(and Nobody Punishes Her for It)

Joan Blondell could sell a wisecrack like nobody else in early Hollywood. In Miss Pinkerton, she gets in plenty of zingers—sarcastic, dry, and perfectly timed. What makes it feel feminist (even if quietly so) is that her wit isn’t played off as something to “fix” or scold.

In a lot of films from the era, a woman who was too sharp had to be softened by the final reel. Not here. Blondell’s Nurse Adams stays sharp all the way through. Her humor helps her survive some seriously tense moments, and nobody asks her to tone it down. She’s clever and funny, and those are the very traits that get her through the mystery alive—and on top.

No Sappy Romance

to Distract from the Plot

Okay, there’s a little hint of potential romance with one of the cops. It’s 1932; we’re lucky they didn’t have her run off and get married at the end. But Miss Pinkerton is refreshingly romance-light. The story doesn’t stop so she can flirt. She doesn’t suddenly get distracted by love in the middle of trying to catch a killer.

Her focus is on the mystery and solving the case. That’s it. And when you consider how many movies, even today, can’t resist adding an unnecessary love story, this one deserves points for letting its leading lady keep her eyes on the prize.

She’s a Proto-Feminist Hero

in a Pre-Code World

One of the sneaky reasons Miss Pinkerton works as a low-key feminist film is because it was made during Hollywood’s Pre-Code era—before the studios slammed the brakes on women having agency. This was a brief window in the early 1930s when female characters could be edgier, more independent, and a whole lot less apologetic.

Nurse Adams doesn’t apologize for being curious or brave or nosy. She doesn’t get punished for stepping out of line. She solves the case, saves the day, and walks out with her dignity (and killer style) intact. For audiences back then—and now—it’s kind of a thrill.

Final Thoughts: Joan Blondell Walked So Veronica Mars Could Run

No, Miss Pinkerton isn’t waving a feminist banner. But Joan Blondell’s turn as a sharp, independent nurse-turned-sleuth feels like the blueprint for every gutsy girl detective who came after her. She was doing it before it was cool—while wearing a killer hat.

If you love a mystery with a side of sass and a heroine who keeps her wits about her (and isn’t afraid to speak them), Miss Pinkerton is absolutely worth a watch.

You must be logged in to post a comment.