Growing up, Mousterpiece Theater on The Disney Channel was something completely new. It didn’t feel instructional, or playful like most kids shows were in the early 1990s. It felt formal. As if I had wandered into a room where something was already in progress, and the only requirement was that I sit quietly and watch.

George Plimpton spoke as though an audience already existed. Not an audience to be won over, but one presumed to be present. His voice carried the cadence of someone accustomed to rooms that listen. Nothing was simplified. Nothing was rushed. The show did not explain itself in advance.

“Genius is not perfection but originality.”

– Arthur Koestler, quoted by George Plimpton

I didn’t understand art history. I didn’t need to then. I understood the posture being asked of me.

Then there was Willie the Operatic Whale.

I didn’t think of him as a character so much as a performer. He arrived the way performers do — already mid-voice, already committed. The music didn’t announce itself as opera. It didn’t pause to introduce its importance. It simply began, and I found myself listening the way an audience listens when it senses that something serious is happening, even if it doesn’t yet understand why.

Willie sang without irony. Without apology. Without the expectation that the room would agree on what he was.

The world inside the story reacted the way audiences sometimes do when confronted with sincerity they didn’t ask for — confusion, projection, disbelief. But the performance continued anyway. Different roles emerged. Different emotional registers. Comedy, sorrow, grandeur, menace. The staging shifted. The voice remained.

I didn’t know what opera was then. I didn’t know that what I was hearing belonged to a lineage, or that it carried centuries behind it. I only knew that the sound required a different kind of attention than anything else on television. It wasn’t asking to be liked. It was asking to be heard.

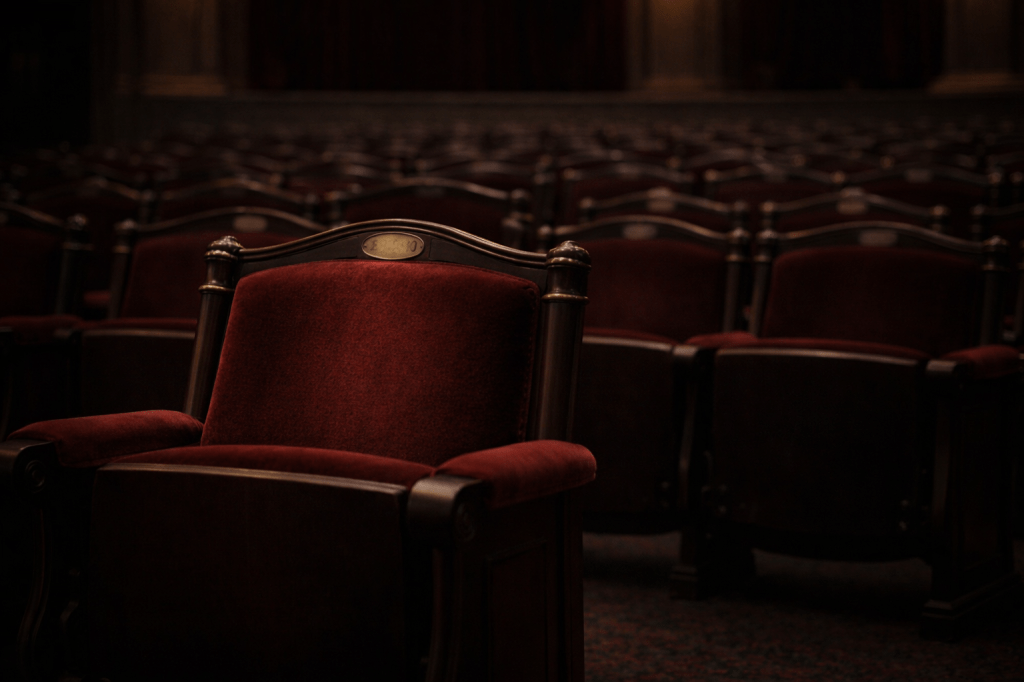

I watched the way you watch from a seat you don’t yet feel entitled to occupy — still, careful, unsure of when to breathe.

Years passed. I didn’t go to the opera. I didn’t pursue that world. I didn’t follow Willie beyond that screen. Something subtle had already happened. I had learned what it felt like to sit in the audience for something larger than myself — something that did not bend toward me for understanding.

Years later, I would see Willie again, rendered as a lobby display outside Mickey’s PhilharMagic at Disney California Adventure in Anaheim, California.

The story did not resolve cleanly. It did not promise that sincerity would be rewarded, or that the world would make room for what it doesn’t recognize. It offered grace without reassurance. The kind that exists after the curtain, when the house lights are still dim and applause doesn’t quite know where to land.

Looking back, I don’t think Mousterpiece Theater introduced me to opera as a destination. It introduced me to the position of listening — to the idea that some forms of beauty do not arrive to entertain, but to exist, whether or not the audience is ready.

Television rarely asked that kind of attention of me then. But Willie did.

I didn’t leave knowing what I had seen.

I left knowing how to sit.

And sometimes that is the first lesson.

“Every exit is an entry somewhere.”

– Tom Stoppard, quoted by George Plimpton

You must be logged in to post a comment.