There’s something quietly haunting about Kelly Reichardt’s 2016 film Certain Women that stays with you long after the credits roll. Set against the windswept backdrop of rural Montana, the film doesn’t shout its themes or try to explain its characters; instead, it invites you to lean in, to sit with the silences, and to notice the small, fragile ways people try to connect. It’s these fragments of connection—fleeting, imperfect, and deeply human—that linger in my mind.

I think about Laura (Laura Dern), sitting in her car after an exhausting day, her face a map of weariness and quiet defeat. She’s the kind of woman who’s competent, patient, and endlessly underestimated. Her client doesn’t listen to her until a male lawyer repeats her advice. It’s a dynamic that feels all too familiar for many women, yet the film doesn’t turn it into a spectacle of outrage. Instead, we’re left to witness Laura’s resignation, the quiet anger that simmers beneath her polite exterior. I wonder about the parts of herself she’s learned to suppress just to get through the day.

Then there’s Gina (Michelle Williams), navigating the uneasy tensions within her family. Her husband’s quiet disinterest and her daughter’s sullen resistance create an undercurrent of isolation. Even in the simplest act—negotiating to buy sandstone from an elderly man—there’s a sense of striving for control, for recognition, for something that’s slipping through her fingers. Gina’s ambition and determination are admirable, but they also seem to alienate her from those around her. It’s as if she’s caught in a balancing act, trying to assert her presence in a world that keeps diminishing it.

Gina’s quiet struggle for control is most evident in this scene, as she and her husband stand by the rock pile under a pale, overcast sky. Their unspoken tensions simmer beneath the surface, reflected in the stillness of the dusty landscape

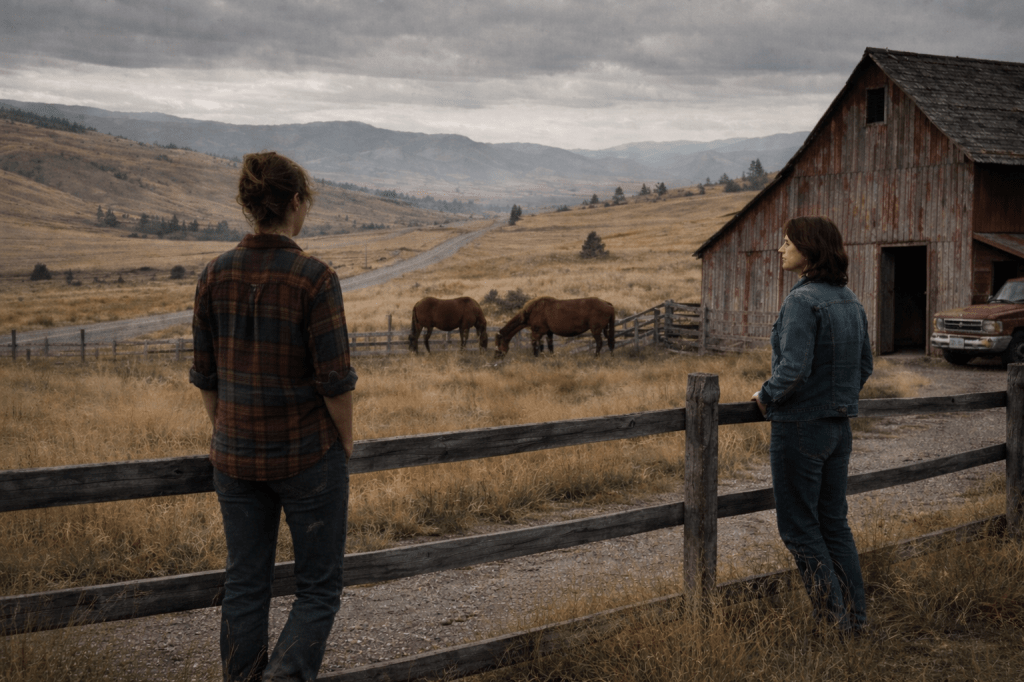

And then there’s Jamie (Lily Gladstone), whose story unfolds with the quietest, most devastating tenderness. She’s a ranch hand, her life shaped by solitude and routine, until she wanders into a night class and meets Beth (Kristen Stewart). The connection between them is delicate and tentative, filled with unspoken longing. Jamie’s yearning is palpable, her gestures—offering Beth a ride, sharing a meal—filled with an almost painful sincerity. When Beth doesn’t return her feelings in the way she hopes, the heartbreak isn’t explosive. It’s a quiet ache, an empty seat at a diner, a horse’s slow walk back to the barn.

Jamie’s quiet longing for Beth is poignantly captured in this tender scene:

What ties these women together isn’t just their struggles or disappointments; it’s the way they keep moving forward, even when the world offers little acknowledgment of their efforts. They live in a landscape—both literal and emotional—that’s vast and unyielding, yet they carve out spaces for themselves within it. Their stories remind me that connection doesn’t always look like a grand gesture or a happy ending. Sometimes, it’s a fleeting moment of understanding, a shared silence, or the quiet resilience of continuing on.

Reichardt’s gift as a filmmaker lies in her ability to capture these moments with such care and authenticity. Watching Certain Women feels like stepping into someone else’s life for a little while, witnessing their struggles and joys without judgment or intrusion. It’s a reminder that even the smallest interactions can carry the weight of something profound.

Personal Reflections

Sitting in the Lake Theater & Cafe in Lake Oswego, Oregon, on this day five years ago, I was struck by how rare it is to see stories like these—stories that honor the interior lives of women without trying to simplify or sensationalize them. That’s what makes Certain Women so quietly revolutionary: it doesn’t offer easy answers or tidy resolutions. Instead, it leaves us with questions, emotions, and the sense that these women’s lives, in all their complexity, matter deeply. And maybe that’s the most powerful connection of all.

You must be logged in to post a comment.