In 1903, film history added a milestone when Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery hit the screen. Instead of still images, the Wild West came alive through kinetic storytelling—gunfights, galloping horses, a gang of outlaws, and a posse of determined lawmen. But what if that same story had starred women instead?

Breaking Barriers in Early Cinema

A women-led Great Train Robbery would have been revolutionary—shattering societal expectations and expanding the limits of what film could do. A director like Alice Guy-Blaché, Lois Weber, or Mabel Normand—women already innovating behind the camera—might have given this action-packed Western a whole new edge.

Now imagine the heist itself: a group of women pulling it off not for riches or notoriety, but because they had no other choice.

Widows. Workers. Women left behind in a world that never made space for them.

Their crime wouldn’t just be rebellion—it would be resistance. A bold, dangerous path to reclaiming power in a man’s world.

A Smarter Heist

The original film is known for its fast-paced action. But in a reimagined version, the women might rely more on strategy and cunning than brute force. Disguises, diversions, and split-second wit could become their strongest tools.

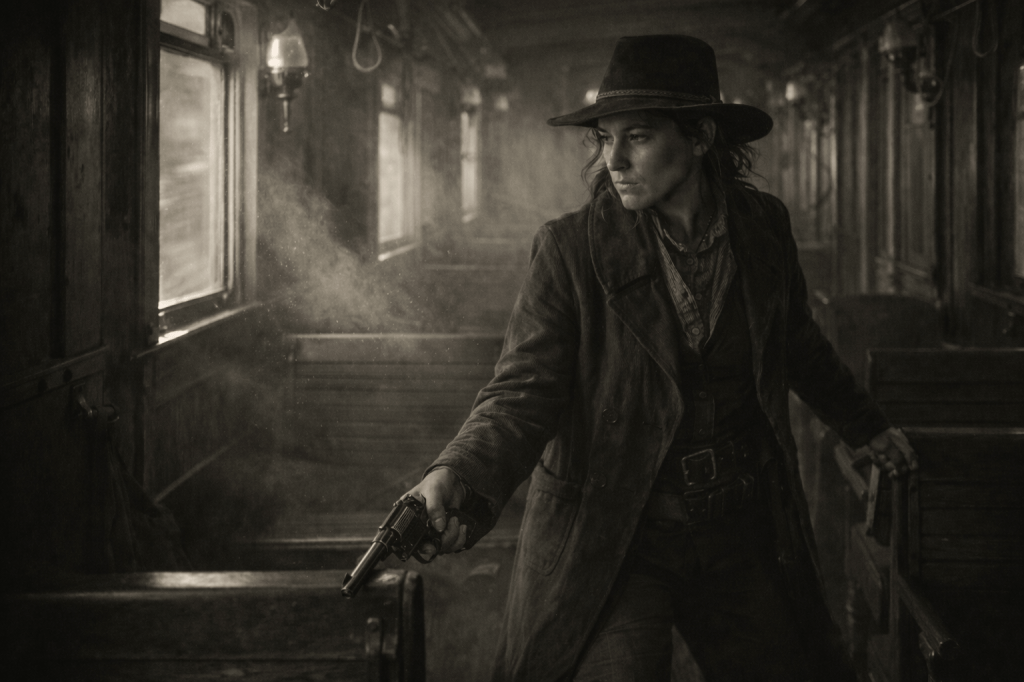

Picture it: instead of storming the train with guns blazing, the women blend in—posing as passengers, workers, even innocents. In a world that underestimates them, their invisibility becomes their advantage.

And the climax? Not a chaotic shootout, but a brilliantly timed redirection. A rusted switch flipped. A sheriff stranded on the wrong track. A train full of secrets vanishing into the trees. The tension lies not in the violence—but in the precision, and the stakes if they fail.

Women on Both Sides of the Law

If the outlaws were women, why not the law enforcers too?

A female sheriff or deputy leading the chase opens up rich narrative ground. What drives her? Duty? Personal loss? A complicated empathy for the women she’s pursuing? Perhaps she sees something of herself in them—a flicker of recognition that challenges her resolve.

And within the gang: are they bonded by friendship, or thrust together by desperation? Is there loyalty, betrayal, doubt? These women wouldn’t just be rebels—they’d be human. Complex, flawed, and navigating a world that has never played fair.

Themes of Rebellion and Survival

While the original Great Train Robbery is a straightforward tale of crime and justice, an all-women version could explore something deeper: systemic oppression, female agency, survival.

Their theft wouldn’t just be a crime—it would be a message. And the story wouldn’t have to end in capture.

Maybe it ends with a quiet escape into the unknown—a final shot of wind in their scarves, dust rising from the tracks, and silence where gunfire might have been.

Maybe it leaves the audience wondering: who really won?

A Cinematic “What If”

In 1903, a film like this would’ve been unthinkable. The male-dominated film industry—and the rigid norms of the time—would never have allowed it. But imagining it today is more than wishful thinking. It’s a way of exploring how storytelling evolves, and how powerfully alternate perspectives can reshape history.

Would audiences back then have embraced it? Some might’ve called it shocking. Others—especially women—might’ve found it thrilling. Liberating. A film like this could’ve opened new doors for female voices in cinema. It could’ve reshaped who we thought could hold the reins, the gun, or the last word.

Because an all-women Great Train Robbery wouldn’t just swap gender roles—it would tell a new story. One of cleverness, resilience, sisterhood, and defiance. It would capture the inventive spirit of early film while challenging its limitations.

Perhaps, in Some Alternate Timeline…

Maybe this film does exist somewhere. A grainy reel flickering in a forgotten projector. A sepia-toned story of women who broke not just the law—but every rule that said they couldn’t.

You must be logged in to post a comment.