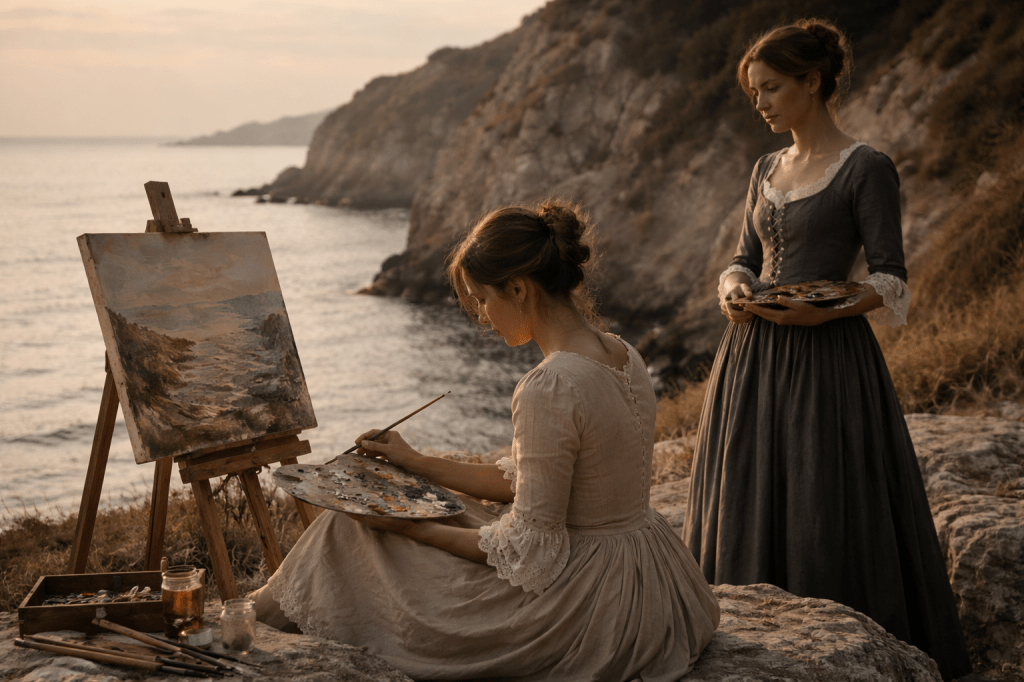

Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire – and my all-time favorite film – employs painting as a rich form of medium for uncovering intimacy, comprehension and the capacity to be truly seen and yet remain unseen. Playing out through the life of the artist Marianne (Noémie Merlant) and her model, Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), the film is translated into a creative and personal reflection of how perception and creation merge with love. The outcome is a story that is not only powerfully emotionally moving, but technically breathtaking to watch.

Observation as the

Foundation of Connection

The connection between Marianne and Héloïse starts with a look. Marianne, a painter, is asked to observe secretly Héloïse while painting her portrait so as not to disturb her. At first, this dynamic feels one-sided. Marianne studies Héloïse from a distance, scrutinizing her every move. But as their bond deepens, observation becomes mutual. Marianne stops looking at Héloïse simply as an artist analyzing her subject and begins to see her as a person she’s falling in love with.

This observation challenges traditional ideas about the muse-artist relationship. In most portrayals the muse is a passive subject, to be inspired or at best, exploited in the artists’ gaze, in the case of sex.

Yet in Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Héloïse becomes involved, directing Marianne’s understanding of her and guiding the creation of the portrait. Their partnership turns the experience of painting from being an observational activity to a collaborative one, where both women make important contributions to the outcome of the process.

Painting as a Mirror of Love

Painting in the film, in fact, is not limited to the reproduction of a physical appearance, but the use of artistic painting allows, most of all, that of a deeper understanding and formation of personal connections. Marianne’s early attempts at Héloïse’s portrait feel incomplete because they’re based on superficial observation. With their relationship deepening the portrait evolves to correspond with the immensity of what binds them.

The making of the painting emphasizes the fragility subjacent to love. Marianne exposes herself through her artistic interpretation, and Héloïse opens herself up to being truly seen. This dyad shares this intimacy of emotion, yet it confounds the roles of artist and muse. The process of painting is inextricably mixed with that of falling in love.

The Power of Being Seen

Marianne’s gaze allows Héloïse to sense things about herself that she might never realise otherwise. To be truly seen—not just looked at, but deeply understood—is transformative. It’s an act of creation, shaping how we view ourselves and how we relate to others.

This experience resonates toward the end of the film, when the only thing that remains of their love and that freezes it—the portrait of their love—is a source of happiness and pain. The picture is imperfect but ageless, a moving image of the ephemeral yet deep impact of their relationship.

A Reflection on Intimacy

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a beautiful meditation on love and art and a powerful use of painting as a mode of representation of a sensual intimacy is one of its deepest functions. The movie makes us question how we perceive the others and how we make ourselves be perceived. Marianne and Héloïse’s story is a reminder that love, like art, requires vulnerability and courage. Seeing and being seen is one of the most potent things that we can experience, and which forms part of the film’s powerful message.

Personal Reactions

Set in another era, it was a beautiful and true representation of the kind of film which I adore – a film made about and by women. Especially when women’s love stories between two women are produced with such skill and nuance by women.

What is it about Portrait of a Lady on Fire that makes it different is its soft, considered pace, which echoes the deepening of the relationships between its protagonists. In a film world ruled by endless remakes and the big budgets of CGI, cinematic refusal to skip ahead feels almost rebellious— a declaration of the world of scenes ripe with sensuality and slow time. In a pandemic altered reality, Portrait of a Lady on Fire feels all the more poignant. Its focus on the importance of connection, memory, and art feels like a poignant reminder of what we hold most dear.

To me, Portrait of a Lady on Fire is the best art film of all time and few if any films could surpass the effect it has on me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.