Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1972 film, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (Die bitteren Tränen der Petra von Kant) is a masterclass in emotional power dynamics and gendered relationships, unfolding within the confines of a single room—a space both lush and claustrophobic, adorned with mannequins, heavy fabrics, and opulent furniture that suffocates as much as it dazzles.

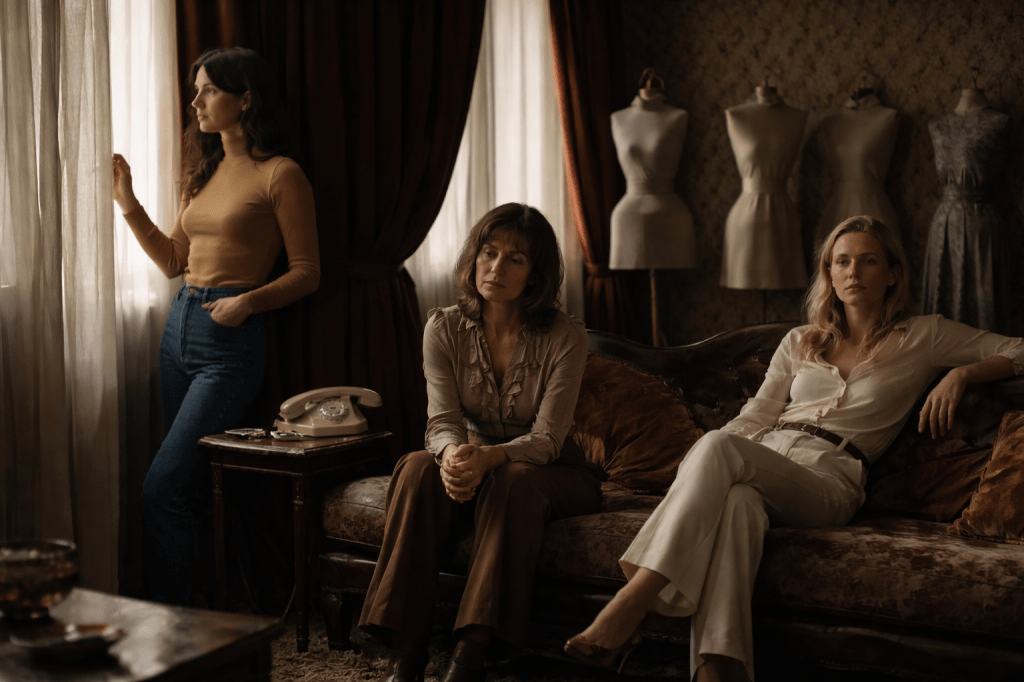

At its heart, the film is a raw exploration of the intersections between love, power, and obsession, as expressed through the lives of three women: Petra von Kant (Margit Carstensen), the commanding fashion designer; Karin Thimm (Hanna Schygulla), the elusive object of her desire; and Marlene (Irm Hermann), the enigmatic assistant whose silence raises questions about subjugation and resistance.

What happens when women navigate power structures imposed by others and self-created? Through a feminist lens, the film reveals itself as a microcosm of this question, exploring the complexities of control, dependency, and resistance.

Petra, Marlene, & Karin

Petra, as the central figure, wields considerable social and financial power. Her dominance over Marlene, and her longing to possess Karin, reflect her own entrapment within a patriarchal framework that equates control with love.

Yet, Petra’s power is far from absolute. Her dependence on both women reveals her vulnerabilities, exposing how even those who dominate are often imprisoned by their own fears and desires.

Marlene, the film’s most intriguing character, stands as a silent witness to these dynamics, her quiet presence laden with questions that linger long after the credits roll.

What drives her loyalty? Is it love, fear, or something more elusive?

Her silence draws us in, forcing us to consider the weight of her gaze and the meaning behind her meticulously executed servitude. While she does not speak, her actions and presence convey a profound resistance. She executes Petra’s commands with precision, but her meticulous servitude becomes a mirror of Petra’s fragility. Through Marlene, Fassbinder subverts the trope of the silent woman: her lack of speech does not signify passivity but rather hints at a quiet rebellion. In the film’s final moments, when Marlene chooses to leave, it is she who ultimately reclaims agency—not by confronting Petra with words, but by removing herself from the oppressive dynamic altogether.

The relationship between Petra and Karin further underscores the complexities of power and vulnerability. Petra’s obsession with Karin is a desperate attempt to assert control over a woman who refuses to be possessed.

Karin’s carefree attitude, her willingness to walk away, makes her unattainable in a way that devastates Petra. Here, Fassbinder highlights the destructive nature of trying to reduce relationships to ownership—a struggle that resonates within broader feminist critiques of traditional power structures in romantic and interpersonal dynamics.

Set In a Single Room

The room itself, the film’s sole setting, functions as a character in its own right, reflecting the entrapment and isolation that these women experience. Its lavish design—mannequins poised like silent witnesses, rich textures cloaking the walls—belies the emotional suffocation within, a space that dazzles even as it confines. Its opulent décor—the mannequins, the lush fabrics, the imposing bed—becomes a stage for their emotional warfare. For Petra, it is both her throne and her prison. For Marlene, it is a workplace and a cage. And for Karin, it is a temporary stopover, one she easily escapes. The room’s claustrophobia serves as a visual metaphor for the limits placed on women’s lives, relationships, and ambitions.

By focusing exclusively on women and their relationships with one another, Fassbinder offers a rare cinematic narrative that eschews the male gaze. Traditionally, the term “male gaze” refers to the way visual media often frames women through a heterosexual, male perspective, reducing them to objects of desire rather than fully realized individuals.

In contrast, Fassbinder’s film examines the complexities of female power and vulnerability without catering to external voyeuristic expectations. Instead, the film delves into the intricacies of female power—how it is wielded, how it is resisted, and how it can ultimately be reclaimed. While Petra, Karin, and Marlene each represent different aspects of this struggle, their interactions underscore a shared truth: the power to define oneself often requires breaking free from the expectations and dependencies that others impose.

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant remains a timeless exploration of these themes, inviting viewers to consider the ways in which gender and power shape our most intimate connections. Through a feminist reading, the film becomes not just a story of heartbreak and obsession, but also a profound commentary on the structures that bind and liberate us.

You must be logged in to post a comment.