Some films choose to whisper. Others, like Je Tu Il Elle (I, You, He, She), hardly speak at all. Chantal Akerman’s 1974 film is a masterclass in restraint—a story built on silence, small actions, and the quiet tension between its characters. It doesn’t guide you with explanations or emotions. Instead, it creates space, inviting you to sit and observe. In its stillness, it becomes unexpectedly loud.

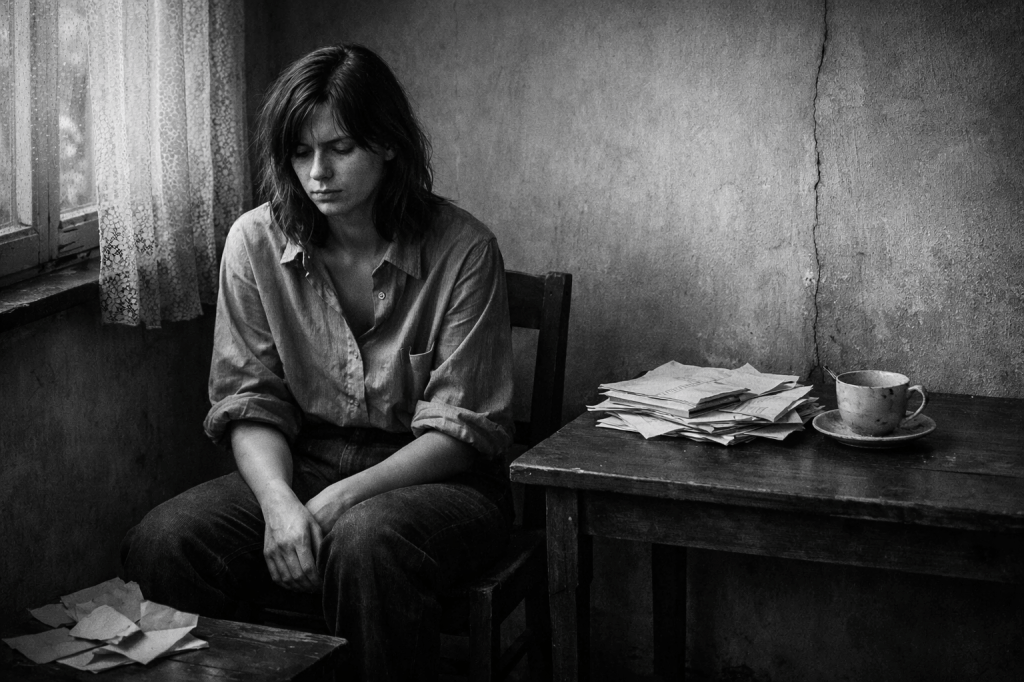

At its heart, Je Tu Il Elle is about a woman’s solitude, her desires, and her search for connection. Akerman herself plays Julie, the protagonist, who spends the first act alone in a small, dimly lit room. The shadows stretch long across the walls, and the stark black-and-white cinematography makes the space feel both suffocating and strangely intimate. She writes letters, eats sugar by the handful, and rearranges furniture with no obvious goal. The silence feels almost physical, interrupted only by the faint scratch of her pen against paper or the soft scrape of a chair leg across the floor. These quiet moments prompt questions: What is she feeling? Is she lonely? Or maybe free? The film never gives you the answers—and it doesn’t need to. Akerman’s vision thrives in that uncertainty.

When she finally ventures beyond the room, she hitches a ride with a truck driver (played by Neils Arestrup). Their exchange is curt, almost clinical. He talks about himself—his marriage, his frustrations—while she listens in silence. Their dynamic, like much of the film, is defined by what’s left unsaid. There’s no overt conversation about power, vulnerability, or the strange intimacy of their shared space. But it’s all there—in their body language, in the pauses. By refusing to spell things out, the connection between them feels raw, even uncomfortably real.

The emotional core of the film arrives in the final act, when the protagonist visits her girlfriend (played by Claire Wauthion). Once again, dialogue takes a backseat to raw, physical expression. Their reunion is intimate and emotionally charged, but the specifics of their relationship remain a mystery.

Why were they apart? Why did the protagonist write her so many letters? Why did she leave?

We don’t know—and obviously we’re not supposed to. Still, their interaction feels achingly familiar, as though we’ve lived something similar—or watched someone else live it. The silences here are heavy, layered with a history we can only imagine.

This is where Je Tu Il Elle finds its strength. By leaving so much unarticulated, it refuses to spoon-feed meaning or impose a neat narrative. Instead, it challenges us to sit with the protagonist’s actions and emotions as they are—messy, unresolved, and profoundly human. Akerman’s trust in her audience to navigate these gaps is what makes the film so impactful.

Even the mundane details—eating sugar straight from the bag, shifting furniture for no clear reason—carry surprising weight. These small acts might seem trivial, but they reveal so much. They feel like attempts at control, quiet rebellions, maybe even gestures of survival. Through them, Akerman taps into something deeply truthful about how we live: the way our actions, no matter how small, can express what words cannot.

Je Tu Il Elle isn’t just a film—it’s an experience. An elegant reminder that what’s not spoken can hold as much weight as what’s shared. Its stillness seems to spark dialogue—not just with the main characters, but with our own thoughts and feelings.

Maybe that’s the point. In life, just like in Je Tu Il Elle, it’s often what we leave unsaid that speaks the loudest.

You must be logged in to post a comment.