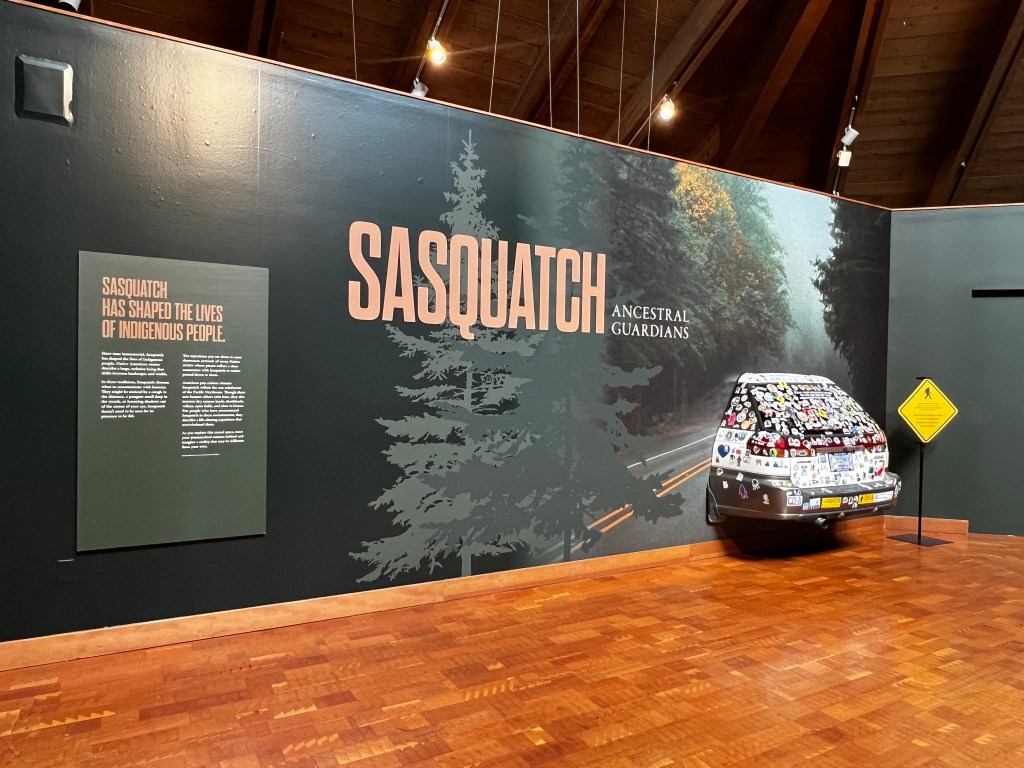

Walking into the Sasquatch: Ancestral Guardians exhibition at the World Forestry Center here in Portland, Oregon, felt unlike any other museum experience I’d had. At first glance, my memories of Sasquatch were rooted in pop culture — the blurry photos, the Patterson–Gimlin footage, bumper stickers, and playful roadside imagery that invites curiosity more than contemplation. Having lived in Oregon my entire life, I didn’t fully realize until later in adulthood how much Sasquatch—Bigfoot—had become an icon of the Pacific Northwest.

But this exhibition invited something deeper: a reframing of that familiar figure in relationship, not spectacle—free from mass-market consumption and the endless churn of “new sighting” narratives.

The phrase that stayed with me most was a quote displayed near the entrance:

“We must walk lightly when we are between worlds with this sacred being.”

— Phillip Cash Cash

That sentiment set the tone for the rest of the exhibition, asking visitors to set aside preconceived notions and step into a space shaped by Indigenous worldviews and stories.

At the exhibition entrance, I noticed a wall where visitors could leave a sticker from their own Sasquatch memorabilia. Instead of simply contributing to kitsch, it felt like a symbolic gesture—placing our cultural assumptions behind us before entering the heart of the exhibition. That act mirrored something I felt personally: an invitation to shift perspective rather than confirm expectation.

The art and installations throughout the space were powerful not because they tried to prove Sasquatch’s existence, but because they emphasized relationships—between humans, forests, and what many Indigenous cultures regard as guardians or relatives.

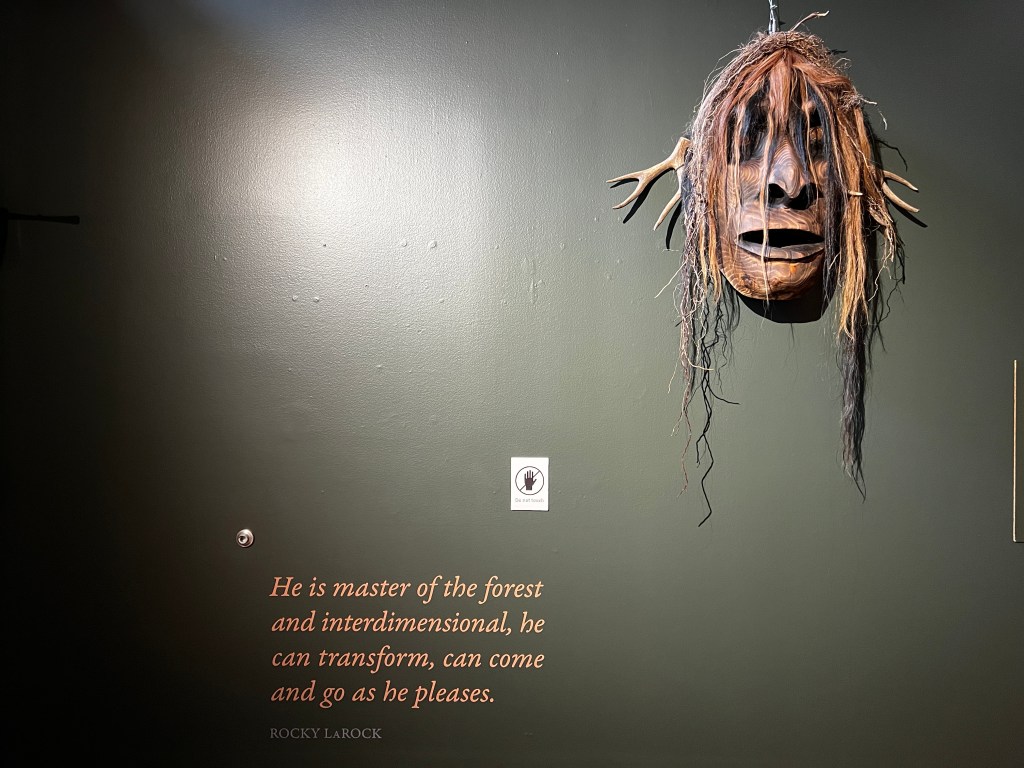

Seeing sculptural works, masks, and pieces drawn from spiritual traditions reminded me how deeply stories and landscapes are intertwined. Here, Sasquatch wasn’t just a cryptid; it was a way of knowing the forest and our place within it.

One piece that stayed with me in particular was a large masked figure that seemed to bridge past and present—ancient traditions meeting contemporary artistic expression. It made me think not only about folklore, but about how stories shape connection: to land, community, and identity.

By centering Indigenous voices—including Nez Perce, Yakama, Warm Springs, Salish, Grand Ronde, and Siletz artists—the exhibition taught me something important. The question is not “Does Sasquatch exist?” but rather, “How are we existing with—and honoring—this non-human other?” That reframing opened space for reflection on how we relate to the forests around us.

Walking out of the World Forestry Center that day, I realized I was holding onto a new kind of curiosity. Not one fueled by mystery, sightings, or myth alone, but one grounded in respect—for culture, for place, and for the many stories that quietly move through the forests we think we know.

All photographs taken by Scott Bryant during a visit to the World Forestry Center.

You must be logged in to post a comment.