The Woman’s Heart

Written By

Golda, Briony, & Rowan

As Told By

Golda

Discovered By

Aisha Rahman, Maeve O’Connell,

Lucía Álvarez, & Nia Thompson

With care and reverence, their story is shared by

Scott Bryant at the request of Aisha Rahman,

Maeve O’Connell, Lucía Álvarez, and Nia Thompson

Act I – The Taking

The forest knew we were coming.

It didn’t stop us. That would have been kinder. Instead, it went still in the way of things that have decided to watch.

Briony noticed first. She always did. She slowed, palm lifted—not a signal, just habit—and the three of us halted on the narrow path where the roots rose like knuckles through the soil.

“No birds,” she murmured.

Rowan tilted her head, listening with her whole body. “No insects either.”

I exhaled and felt it fog the air. “Good,” I said quietly. “Means we’re expected.”

That earned me a look from Briony, sharp and familiar. I smiled back, because if you don’t smile at moments like that, you start naming your fear, and fear gets ideas.

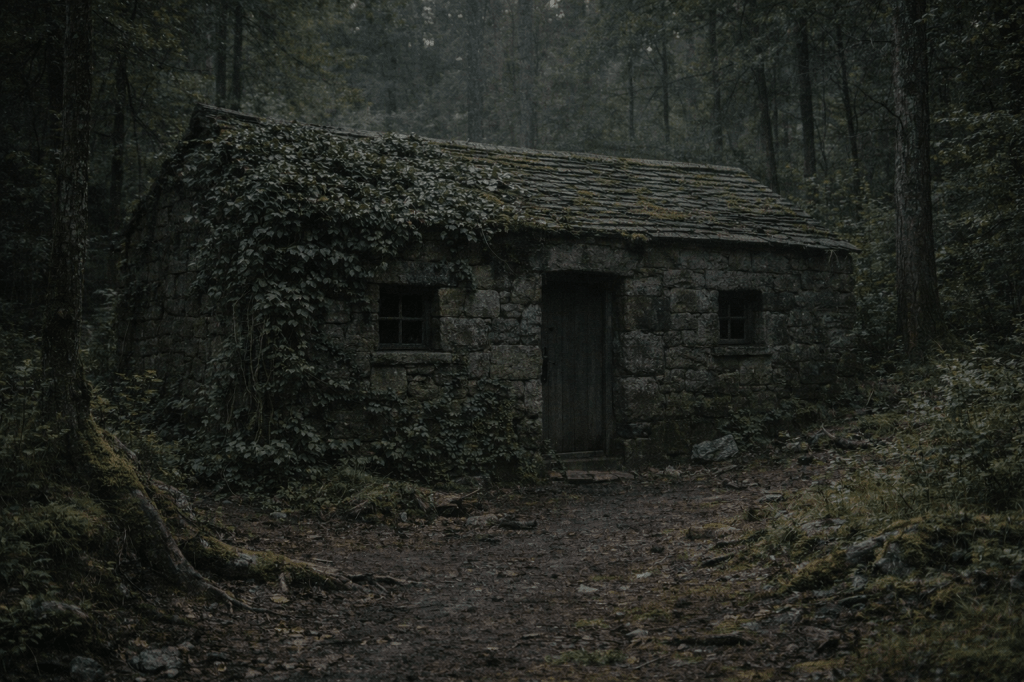

Ursa’s woods were older than ours. You could feel it in the way the ground resisted your steps, as if it remembered a time before feet. The trees leaned closer together here, their branches braided high overhead. Not protective. Proprietary.

We moved on, slow and deliberate, the way women do once they’ve learned what haste really is.

Ursa’s cottage sat where the path gave up pretending to be friendly. No fence. No welcome. Just a low stone house pressed into the earth like it had been grown there rather than built. Ivy crawled across the walls, not wild but trained, each leaf glossy and alert.

“Wards?” I whispered.

Briony crouched, brushing ash from her fingers into the dirt. The runes flared faintly, then dimmed. “Of course there are wards. If there weren’t, I’d be offended.”

Rowan’s mouth twitched. “She does like her dignity.”

“Ursa likes control,” I said. “Dignity is just what she calls it when no one’s laughing.”

That earned me a soft snort from Rowan. It felt good—normal. Dangerous things always do, right before they aren’t.

We slipped the first ward the way you slip a ring off a sleeping hand. The second took longer. The third bit.

I hissed as heat snapped across my knuckles.

“Don’t rush,” Briony whispered, not unkindly.

“I wasn’t rushing,” I said. “I was… asserting familiarity.”

“That’s rushing with opinions,” Rowan said.

I pressed my palm to the stone until the sting faded. The cottage exhaled, like it had been holding its breath. Somewhere inside, glass chimed.

We waited.

Nothing came.

“That’s worse,” Briony said.

We entered anyway.

Ursa’s cottage smelled like honey and iron. Shelves lined the walls, crowded with jars—roots, feathers, things that pulsed faintly when you looked too long. Mirrors hung everywhere, angled so no matter where you stood, you saw yourself from three directions. Clever woman. Paranoid woman.

I kept my eyes on the floor.

The Heart was easy to find. It wanted to be.

It sat on a low pedestal of twisted wood at the back of the room, glowing softly, like embers beneath ash. Not blazing. Not begging. Just waiting.

Rowan stopped breathing when she saw it. Briony swore under her breath—something old and academic.

I felt it before I touched it. Warm. Familiar. Like coming home and realizing the house has been cold without you.

“This is a terrible idea,” Briony said.

“Yes,” I agreed, already reaching out.

The moment my fingers closed around the jewel, the cottage shuddered.

Not violently. Not yet.

The mirrors darkened. The jars rattled. Somewhere deep in the walls, something growled—not an animal sound, but the echo of one.

Rowan grabbed my arm. “Golda.”

“I know,” I said. “I know.”

The Heart pulsed once. Then again. Slow. Steady.

Outside, the forest inhaled.

“We have it,” Briony said. “Which means we should leave. Immediately. Without commentary.”

We didn’t run. Running tells the world you think it can catch you.

We walked back into the trees, the path unfolding reluctantly beneath our feet. Behind us, Ursa’s cottage settled into silence again—too neat, too composed.

Only when we were well beyond the first ring of oaks did Rowan let out a breath.

“She’ll know,” she said.

“Yes,” I said.

“When?”

I glanced at the Heart, glowing steadily in my hands, warm as a living thing.

Ursa had always known where to look when something went missing.

“Soon,” I said. “And she won’t knock.”

We didn’t laugh at that. But Briony did reach out and squeeze my shoulder, once.

That was enough.

Behind us, somewhere deep in the woods, something vast and patient began to wake.

Act II – The Siege

Home did not look the way it should have.

Our cottage sat where it always had, crouched against the hill like an old animal that had learned not to spook easily. Smoke drifted from the chimney. Light glowed in the windows. Everything said welcome back.

The forest said nothing at all.

Rowan felt it too. She slowed, her hand brushing the low stone wall as if checking a pulse. “She hasn’t followed us,” she said, carefully.

“Yet,” Briony replied.

I didn’t answer. I was listening to the Heart.

It pulsed against my ribs where I’d tucked it inside my coat, steady and calm, like it trusted us. That was almost worse than if it had panicked.

Inside, the cottage smelled of oats and dried apples. The kettle sat where we’d left it. Rowan’s herbs hung in orderly disarray from the beams. Briony’s books were stacked in disciplined towers that dared gravity to try something.

I set the Heart on the table. It brightened the room immediately—not blazing, just… present. The walls seemed to ease, like shoulders dropping after a long day.

“Well,” Briony said, shrugging off her cloak. “We’ve stolen from a powerful sorceress, angered an ancient forest, and survived the walk home. I propose porridge.”

Rowan laughed softly. “Celebratory porridge.”

“Defiant porridge,” I corrected. “She’d hate that.”

That earned me a look from Briony. “Everything we do annoys Ursa.”

“Yes,” I said. “But eating well while doing it feels pointed.”

The kettle sang. Rowan stirred. For a few minutes, it almost worked—normalcy, warmth, the comfort of routine. The kind of domestic magic you don’t write spells for because it’s older than words.

We sat. We ate. The Heart glowed between us, catching the firelight.

Then the wind shifted.

Not outside—inside the room. A slow, deliberate movement, like someone turning their head.

Rowan froze, spoon halfway to her mouth. “Did you—”

A low sound rolled through the floorboards. Not loud. Not threatening. Just… there.

Briony set her bowl down. “That’s not the house.”

“No,” I said quietly. “That’s her.”

The sound faded. The cottage exhaled again, pretending nothing had happened.

Briony frowned. “That was too fast.”

I didn’t like that either.

“She knows we took it,” Rowan said. “But she doesn’t know where we are.”

I looked at the Heart. “She always knows where to look.”

We didn’t say anything for a moment.

Then Briony sighed. “Right. I’m checking the wards.”

“And I’ll—” Rowan gestured vaguely upward. “Have a look around.”

I grinned despite myself. “Birds?”

“Birds,” she agreed. “Quiet ones.”

Briony shot her a look. “Do not antagonize her.”

Rowan’s mouth curved. “I would never.”

We stepped outside into the night, the moon thin and sharp above the trees. The forest watched us again now—curious, not hostile.

The change came easily. Feathers where skin had been. Bones hollowed and light. The world tilted into air and branch.

We took the pine overlooking Ursa’s clearing without effort, three shadows settling into needles and bark.

Her cottage below was no longer composed.

Green light leaked from the windows. The ground around it was scarred with sigils carved too deeply, as if patience had been abandoned midway through precision.

Ursa moved inside like a storm held in a bottle.

Even from above, I could feel her—contained fury, elegant and sharp. She paced, speaking to mirrors, to the Heart’s absence, to herself.

“She’s upset,” Rowan thought mildly.

Briony’s raven-form clicked its beak. She’s restraining herself.

That was worse.

Ursa stopped suddenly. Her head turned—not toward us, not quite—but toward the sound we’d forgotten to stop making.

Three owls.

Three fools.

“Who?” Rowan hooted.

Briony followed a half-beat later. “Who?”

I hesitated—then joined them. “Who?”

Inside the cottage, Ursa went very still.

She didn’t look up.

She smiled.

Not wide. Not cruel. Just knowing.

“Who indeed,” she murmured, voice carrying like smoke.

The clearing went cold.

Rowan’s wings twitched. Time to go.

“Yes,” I agreed, already lifting. Fun’s over.

We took to the air laughing—quiet, breathless, ridiculous laughter—because sometimes the only way to outrun fear is to pretend it’s a game.

Behind us, Ursa raised her hands.

The ground answered.

Something vast stirred beneath the roots.

And far above the trees, a constellation the old stories called The Bear seemed to lean closer to the earth.

Night One – The Porridge

We did not sleep.

That was our first mistake. Or maybe our only sensible choice—we never did agree afterward.

By the time night settled properly, the cottage had been walked, warded, checked, and checked again. Briony muttered to the walls. Rowan whispered to the hearth. I sat at the table with the Heart between my palms, feeling its steady patience like a second pulse.

“She’s waiting,” Rowan said at last.

“For what?” Briony asked.

“For us to relax.”

We did, eventually. You can’t stay braced forever; your bones refuse. So we made porridge. Thick oats, a little salt, honey if you squinted. The kind of food that pretends the world is manageable.

I had just sat down when Rowan frowned.

“I’ll step outside,” she said. “Just for a moment.”

Briony sighed. “You said that last time.”

“And we lived.”

Rowan wrapped her cloak tighter and slipped out the door.

I lifted my spoon. Steam curled up, warm and ordinary. For a heartbeat, I thought—foolishly—that perhaps Ursa would choose elegance. A curse. A storm. Something clever and survivable.

The ground shuddered.

Not a tremor. A decision.

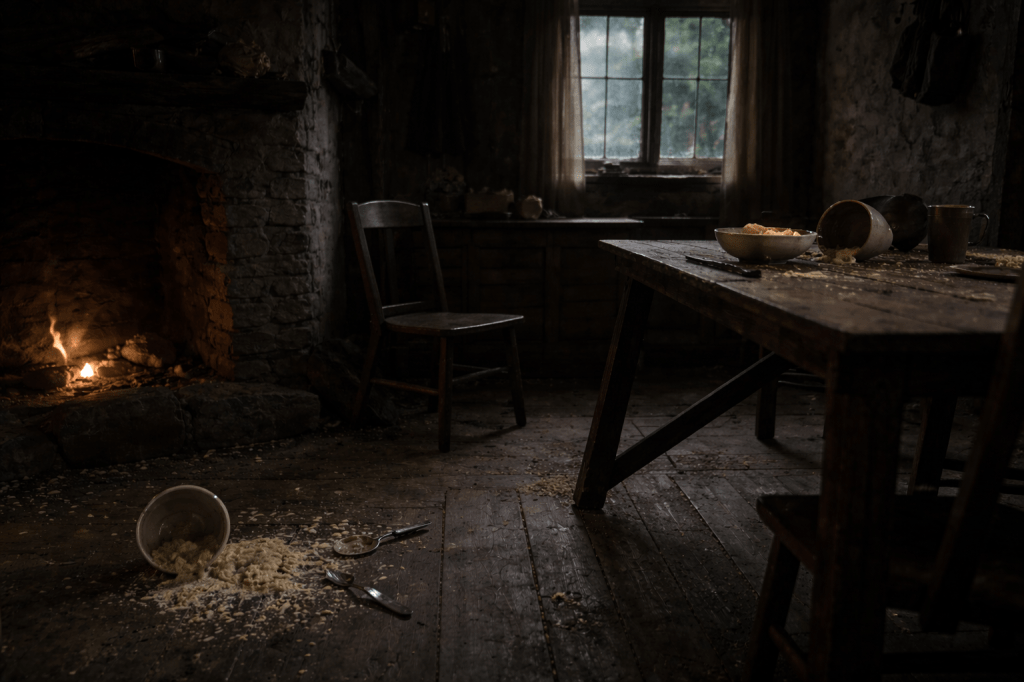

The bowls rattled. The kettle screamed. Ash spilled from the hearth like startled birds.

Briony was already on her feet. “That’s—”

The door flew open.

Rowan burst inside, eyes bright, breath gone. “Golda,” she said, very calmly, “we have a bear.”

The word barely settled before the sound arrived—breath like wind through a cave, a low, rolling growl that pressed against the walls and made the cottage remember it was small.

I stood. Slowly. Because panic makes noise, and noise draws attention.

Outside, something massive shifted. The trees groaned. Bark split. The forest leaned away from itself.

“That’s not a bear,” Briony said faintly.

The shadow passed the window.

Fur. Dark and matted, streaked with green light. A shoulder broader than the doorframe. Claws that scored the stone as if it were chalk.

The cottage creaked in protest.

“Well,” I said, because someone had to, “she’s escalated.”

The wall bowed inward.

Briony snapped her fingers and the wards flared—lines of light stitching themselves across the door just as something slammed into it. The impact threw Rowan against the table. Porridge sloshed, thick and obscene, across the floor.

The bear roared.

It was not an animal sound. It carried memory. Grief. Rage sharpened to purpose.

I felt the Heart answer, pulsing harder now, as if recognizing an old name spoken too loudly.

“Ursa,” I said without thinking.

The roar stuttered.

Just for a moment.

Then the door cracked.

“Right,” Rowan gasped, hauling herself upright. “Next time we steal something, let’s not antagonize the owner.”

Briony laughed—a short, wild sound. “She broke my favorite chair.”

“That was tomorrow,” I said. “Focus.”

The bear hit the cottage again, harder this time. The wards screamed. Cracks spidered across the frame.

We moved together then, as we always had. Not fast. Not frantic. Just precise.

Briony shored the walls. Rowan called the wind down the chimney. I lifted the Heart and felt its heat bloom, bright as dawn behind my ribs.

Outside, the bear circled.

Patient. Furious. Certain.

This was not a warning.

This was a promise.

And as the first ward shattered and the cottage cried out like a living thing, I had the strangest, clearest thought:

We should have eaten faster.

The bear did not break through.

That was the mercy of it. Or the calculation.

She slammed the cottage one last time—enough to remind us she could—and then she stopped. The silence afterward rang louder than the roar had.

We stood there, breathing hard, the Heart dimming back to its patient glow. Smoke drifted from the wards where Briony’s runes had burned themselves thin. The floor was slick with spilled porridge, trampled with soot and ash.

Outside, branches cracked as the bear moved away. Not retreating. Circling wider. Learning.

Rowan slid down the wall and sat, her back against the stones. “She wanted us awake,” she said.

“Yes,” I agreed. “And afraid.”

Briony inspected the doorframe with professional disdain. “She also wanted to see what we’d do.”

“And?” Rowan asked.

Briony sniffed. “We did adequately.”

That earned a weak laugh from Rowan. I leaned against the table and let my hands shake now that no one needed them steady.

The forest slowly remembered how to breathe. Night insects returned, tentative at first. Somewhere far off, something hooted—not one of ours.

“She’ll be back,” Rowan said.

“Of course she will,” Briony replied. “She hasn’t broken anything important yet.”

I glanced at the Heart. “She has.”

We cleaned because that’s what you do when terror leaves a mess behind. Rowan swept. Briony reset what wards she could salvage. I scraped porridge off the floor and pretended not to mourn it.

Eventually, we sat again—no bowls this time. Just mugs of bitter tea and the sound of the cottage settling around us, injured but stubborn.

“She knows where we live,” Rowan said.

“Yes.”

“She knows we won’t run.”

“Yes.”

Briony stared into her cup. “Then we should stop pretending this is a single night’s problem.”

I nodded. “Agreed.”

Outside, something large exhaled. Not close. Not far.

We did not sleep after that. We listened. We waited. Dawn came thin and gray, like it had second thoughts.

Ursa did not return before morning.

That was how we knew she was planning.

Night Two – The Chairs

By daylight, the cottage looked like it had survived an argument with a god and lost politely.

The door sagged. One wall bowed inward. Briony’s favorite chair lay in pieces, its legs snapped cleanly, as if to make a point.

Briony stared at it for a long moment.

“Well,” she said at last. “That’s personal.”

Rowan rubbed her eyes. “She broke the wrong one.”

I set the kettle on. “Then tonight we don’t wait to be surprised.”

We spent the day preparing—not frantically, not bravely. Methodically. Briony redrew wards thicker this time, layered like arguments she expected to have to repeat. Rowan coaxed the wind into new paths, teaching it where it was allowed to go and where it wasn’t.

I moved the chairs.

Not just out of the way—into a circle. Close together. Familiar. The kind of arrangement you choose when you expect to sit a long while with the same people and see what comes of it.

Rowan watched me. “You think she’ll come back tonight?”

I smiled, tired and certain. “Yes.”

Briony flexed her fingers, sparks snapping faintly at the tips. “Good. I’d hate for her to think she made an impression.”

Outside, the forest leaned closer again.

The chairs waited.

Ursa came before sunset.

That was her first improvement.

The forest announced her without ceremony. Birds fled. Wind folded itself away. The light dimmed as if the evening had decided not to commit.

“She’s early,” Rowan said.

“She’s efficient,” Briony corrected.

We took our places in the circle of chairs, backs straight, feet planted. The Heart rested on the low table between us, glowing softly, like it was trying not to draw attention to itself.

I hated that I understood the impulse.

The first impact did not come at the door.

It came at the ground.

The cottage lurched as something heavy slammed into the earth beneath the windows, testing. The walls flexed, then steadied. Briony’s wards hummed, low and annoyed.

Outside, a shape moved past the glass—close enough that I could see fur brushed with moss, scars glowing faintly green.

“She’s learning,” Rowan whispered.

“Yes,” I said. “And she’s offended we learned too.”

Ursa did not roar this time.

She scraped.

Claws dragged slowly across stone, deliberate as writing. The sound made my teeth ache. The cottage shuddered, holding.

Briony leaned toward me, voice dry as dust. “If she starts spelling our names, I’m leaving.”

Rowan snorted despite herself.

The bear circled. Once. Twice. Each pass closer. Each time, she struck—not with full force, but enough to test the layers. The wards flared, dimmed, flared again.

“She’s pacing herself,” Rowan said. “Like she’s enjoying it.”

“That was always her worst quality,” I replied.

The third strike came higher.

The window exploded inward.

Glass flew. Wind followed. Fur filled the frame—massive, dark, alive. The bear thrust her head inside, jaws snapping inches from Rowan’s chair.

Rowan shrieked and flung a spell so fast it came out sideways. The wind slammed the bear’s muzzle back, hard enough to crack the sill.

Ursa roared then—not in pain, but in triumph.

The cottage groaned.

Briony stood, hands blazing with sigils. “Golda.”

“Now,” I said.

We moved together.

Briony locked the walls, reinforcing the spine of the house. Rowan pulled the air tight, turning it thick and uncooperative. I lifted the Heart and let its light spill—not outward, but inward, flooding the room with warmth and memory.

Outside, the bear faltered.

Just for a breath.

“Ursa,” I said again, louder this time. “This is foolish.”

Her eyes found me through the shattered window—amber, furious, terribly human.

She spoke.

Not words. Not quite.

But meaning pressed into sound.

You took what was mine.

Rowan gasped. Briony swore.

“It was never yours,” I said. “You know that.”

The bear slammed her weight against the wall.

Something cracked—not stone, but resolve.

The chair beside Rowan shattered, flung aside like kindling.

Briony stared at the wreckage. “That was my second favorite.”

Ursa surged forward again, closer now, claws scraping deep grooves into the threshold. She could have broken through if she wanted.

She didn’t.

She leaned in, breath steaming through the broken window, carrying the scent of earth and old blood.

She was smiling.

Then she withdrew.

The forest exhaled in relief that felt premature.

Silence fell, heavy and wrong.

Rowan collapsed back into her chair. “She could have—”

“Yes,” I said. “She could have.”

Briony rubbed soot from her cheek. “She wanted us to feel it.”

Outside, something large moved away—slow, unhurried.

“She’s not trying to destroy the cottage,” Rowan said.

“No,” I agreed. “She’s trying to enter it.”

We sat in the wreckage, the circle broken now, chairs splintered and scarred. The Heart pulsed brighter than it had before, as if frightened.

Briony looked around the room, eyes sharp despite exhaustion. “Tomorrow,” she said, “we reinforce the beds.”

Rowan groaned. “I was hoping we wouldn’t get to that part.”

I laughed—soft, tired, real. “We always get to that part.”

Outside, the stars blinked into place, distant and uncaring. Somewhere above them, the Bear watched.

Ursa had tested our walls.

Tomorrow night, she would test our rest.

And I knew, with the calm certainty that comes only after fear has settled into resolve—

she would not stop at the threshold again.

Act III – The Reckoning

Night Three – The Beds

We slept that day.

Not well. Not deeply. But enough to remind our bodies what rest felt like, so they would know what they were losing.

By dusk, the cottage no longer pretended to be whole. Chairs were gone, windows patched with spelllight and will. The door leaned inward like a tired mouth. Only the beds remained untouched—three narrow frames pushed together in the center of the room, quilts folded back, bare and waiting.

Briony traced the last of the runes into the floorboards around them, slower than usual. Rowan braided her hair with herbs I didn’t recognize. I placed the Heart at the foot of the beds and felt it tremble.

“She’ll come through this time,” Rowan said.

“Yes,” I replied.

Briony straightened. “Good. I dislike suspense.”

Night fell all at once.

The forest did not announce Ursa’s arrival.

There was no warning. No pacing. No testing.

The ground simply rose.

The cottage screamed as stone split and earth heaved. The wall opposite the beds burst inward, not shattered but pushed aside, as if it had offended something larger than architecture.

Ursa came through the ruin like a living hill.

She was magnificent.

Fur tangled with moss and briar, eyes burning with starfire, shoulders brushing the beams as if the house were a suggestion rather than a boundary. Every breath she took pulled the night toward her.

Fear left me then.

Not because she was less terrifying—but because terror had reached its limit and tipped into something else.

Awe.

“Ursa,” I said, and this time it was not a warning. It was a name remembered.

She paused.

The beds shuddered as she stepped closer, claws sinking into the floorboards inches from where we stood. Briony’s wards flared white-hot. Rowan’s wind howled through the shattered walls, wrapping the room in a living storm.

Ursa roared, and the sound carried grief so old it made my chest ache.

I gave everything, the sound said.

I kept the forest alive.

I was forgotten.

Rowan wept openly now, wind stuttering with her breath. “She’s not wrong.”

“No,” I said softly. “She’s not.”

Briony shouted an incantation that snapped like lightning. Ursa reeled, more startled than hurt.

I stepped forward, bare feet on splintered wood, and lifted the Heart.

Its light filled the room—not blinding, but complete. It remembered every woman who had poured herself into the forest and been held in return.

“Ursa,” I said again. “You were never alone.”

Her great head lowered. For a heartbeat, I saw the woman she had been—elegant, furious, brilliant, unbearably lonely.

The bear shook.

The forest groaned.

Ursa lunged.

Not at us.

At the Heart.

Briony screamed. Rowan grabbed my arm. I did the only thing left.

I let go.

The Heart fell into Ursa’s chest like it had been waiting there all along.

Light exploded—not outward, but inward. The bear howled, sound breaking into sobs, into silence.

When it cleared, Ursa lay where she had fallen, fur already fading, breath shallow, human eyes staring at the dawn creeping through the trees.

She looked at me. “Golda,” she whispered.

“Yes,” I said, kneeling beside her.

“I wanted to be enough,” she said.

“You were,” Rowan replied, voice steady despite the tears. “You just forgot how to share.”

Ursa smiled, faint and tired. Then she was gone.

The forest exhaled.

The cottage did not survive. But we did.

We sat together on the ruins of our beds as morning broke, wrapped in blankets, soot-streaked and shaking.

Rowan found the last bowl of porridge—cold, forgotten, miraculously intact.

She tasted it and made a face. “Too cold.”

Briony tried it next. “Too thick.”

They looked at me.

I smiled. “Just right.”

Outside, a bird called.

Far above the trees, a constellation shifted—one star burning brighter than it had before, watching over the forest she had once loved too fiercely to let go.

And that is how the woods learned to breathe again.

Epilogue

They ask sometimes what happened to the bear.

People always do. They like their endings solid—bones to bury, tracks to follow. I tell them what is true and let them decide which part to believe.

I say the forest grew quieter after Ursa died. Not empty. Just… settled. The trees stopped leaning away from themselves. The paths remembered where they were meant to go. On clear nights, the stars above the hollow seem to hold their breath a moment longer than elsewhere.

Our cottage did not survive. We rebuilt it smaller, closer to the ground. The new door opens easily. We learned something about thresholds.

Briony insists the chairs are sturdier now. Rowan talks to the birds as if they’ve always answered back. I still make porridge most mornings. Some habits don’t need improving.

They’ve given the bear a name, of course. The Bracken Queen. Old Honey-Mother. The Last Bear of Albion. Stories love a crown.

We do not correct them.

Once, not long ago, I looked up and saw a star where there hadn’t been one before—bright, steady, watching. I don’t know if it’s Ursa. I only know the forest looks back at it like it’s been forgiven.

If you listen closely in these woods, you can still hear her sometimes. Not roaring. Breathing. As if the land itself has remembered how.

And if you ever hear three women laughing in the trees—soft, familiar, unafraid—don’t worry.

It only means the forest is being looked after.

You must be logged in to post a comment.