Notes from the making of The Woman’s Heart

This document sits beside The Woman’s Heart, not inside it.

These are fragments, attempts, and notes from moments we tried to visualize and eventually chose not to. Not because the images failed—but because they changed the story when we lingered on them.

What follows isn’t a record of mistakes.

It’s a record of restraint.

On Wanting to Show Ursa

We wanted to show Ursa.

At first, that felt obvious. She was present. She was enormous. She left marks. It seemed reasonable to let the camera meet her where the text did.

Every attempt made her clearer—and in doing so, simpler.

The more visible she became, the more the story tilted toward her body, her scale, her force. Fear became easier to access, but harder to listen through. The women’s endurance began to recede behind her presence.

We didn’t underestimate Ursa’s power.

We underestimated its duration.

By the time the story opens, Ursa isn’t guarding something. She has been holding it—alone—for longer than anyone remembers. Showing her reduced that accumulation to a moment. Listening preserved it.

In the end, we decided Ursa deserved to be heard, not seen—not because of how she looked, but because listening kept the story grounded in consequence rather than spectacle.

Once seen, she began to collect explanation too quickly.

The story didn’t need another person to understand.

It needed a force that could not be resolved by looking.

The Night Sections and Restraint

The three nights in the story are not equal.

The first night miscalculates.

The second adapts.

The third resolves something that can’t be undone.

We discovered early that trying to illustrate each night flattened that movement. Images wanted to escalate when the story needed to settle.

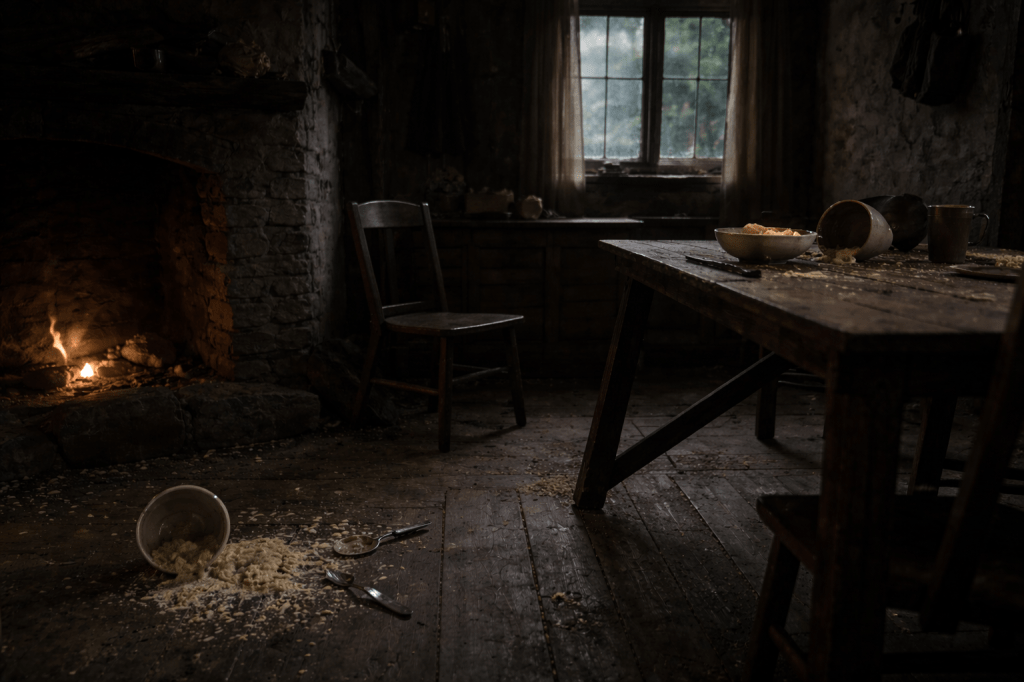

Only one image earned its place among the nights: the aftermath of the porridge.

It worked because nothing was happening anymore.

It showed interruption, not action.

Pressure, not violence.

Evidence without explanation.

Anything beyond that began to speak louder than the room itself.

After the Porridge

This was the closest we came to showing the intrusion directly—and the moment we understood what kind of images the story could tolerate.

The porridge mattered because it was ordinary.

Because it was meant to be eaten.

Because it was wasted without ceremony.

The room survived not because it resisted, but because whatever entered it chose to leave.

That distinction mattered.

On Chairs

We tried to show the chairs.

Before. During. After.

They never stayed still long enough to mean only one thing.

When we fixed them in an image, they became symbolic too quickly—arranged, legible, decided. In the text, they resist that. They scrape, shift, splinter, interrupt posture.

Language held them better than the camera did.

On Beds

The same was true of the beds.

Once shown, they became vulnerable in a way the story hadn’t earned yet. The image rushed intimacy the prose was still circling.

Some thresholds need to be crossed in time, not space.

What the Images Kept Teaching Us

Every visual attempt answered the same question:

Was this image listening — or announcing?

When images listened, they stayed.

When they announced, they left.

So we stopped asking them to behave.

A Final Note

The Woman’s Heart didn’t need more images. It needed fewer decisions.

These notes are what remained after we stopped insisting on seeing everything.

You must be logged in to post a comment.