In discussions of Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise (1932), attention often settles on wit—on elegance, implication, the famous “Lubitsch touch.” But the film’s true sophistication rests elsewhere. It lies in its women, and in the refusal to discipline them for knowing exactly how the world works.

Miriam Hopkins and Kay Francis do not represent opposing moral poles. They represent parallel forms of intelligence.

Hopkins’s Lily is adaptive, performative, and mobile. She understands that identity can be worn, adjusted, abandoned. Her intelligence is kinetic—reading rooms, calibrating tone, moving between social registers without apology. The film does not frame this as deception so much as fluency.

Kay Francis’s Madame Mariette Colet, by contrast, is composed and economically secure. Her authority is quieter but no less acute. She does not need to maneuver; she can afford clarity. Crucially, she recognizes Lily’s intelligence almost immediately. There is no prolonged rivalry staged for punishment or spectacle. Instead, there is assessment—and respect.

What does not happen in the film matters as much as what does. Neither woman is humiliated. Neither is morally corrected. Desire does not invalidate judgment, and intelligence does not require sacrifice. When the story resolves, it does so without stripping either woman of dignity.

This is a Pre-Code vision of female autonomy that does not announce itself as radical. It simply assumes women are capable of understanding systems of power—and choosing how to engage them.

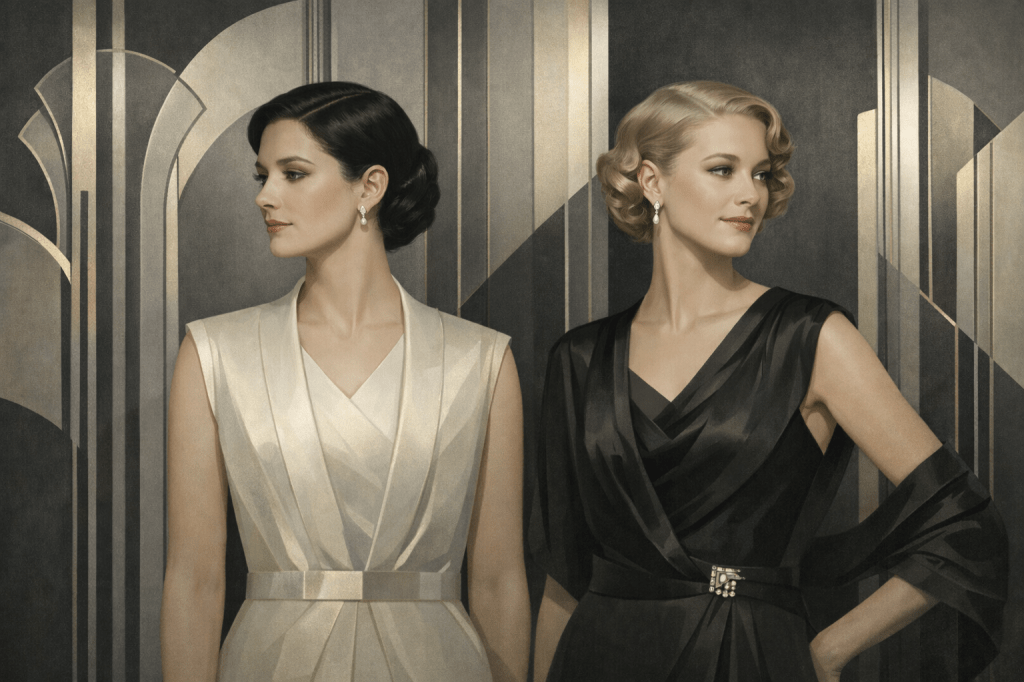

What endures in Trouble in Paradise is not its cleverness, but its composure. The film understands that power does not always announce itself through conquest or correction. Sometimes it resides in placement—in knowing where one stands, what one sees, and which structures are navigable without surrender. The women at its center are not defined by rivalry or romance, but by parallel awareness: each fluent in systems, each intact within them. Like the architectural forms that frame rather than overwhelm, their intelligence is legible through balance, not display. The film does not ask us to choose between them. It asks us to recognize what it means, still, to let women remain whole.

You must be logged in to post a comment.