Merry Wives of Windsor

Tigard High School Theatre Department —

November 8th, 2025

Deb Fennell Auditorium, Tigard, Oregon

Directed by Tori Lee Scoles & Caitlin Lushington

By William Shakespeare

The Saturday afternoon light fell softly over Tigard High School — low November sunlight, amber and forgiving, the kind that turns even parking-lot pavement into something painterly.

The air was cool and bright, the faint scent of pine and damp leaves drifting from the edge of the lot. From the outside, the Deb Fennell Auditorium looks like so many civic landmarks built in the mid-century Northwest — crisp lines, cream-white façade, metal panels catching the light. There’s nothing ostentatious about it, but the structure has presence, the kind that feels rooted in its community. You sense that countless memories have passed through those glass doors: graduations, assemblies, concerts, plays. On this afternoon, it held something more fragile and rare — the promise of whimsy protected, of laughter made sacred.

Inside the lobby, the student lobby crew moved with a kind of organized warmth. There’s a particular electricity to student theatre; it hums in the air before the lights even dim. You can feel it in the small talk, the rustle of programs, the proud glance of a parent holding a bouquet.

I found my seat early, close enough to see the actors’ expressions but far enough back to take in the full picture.

The stage was minimal: a modular set evoking a 1960s resort town, a palette of bright colors and retro shapes. Even before the lights dimmed, the soundscape told its own story — a playlist of smoky jazz and bossa nova filling the space. It was a subtle masterstroke, bridging Shakespeare’s wit with midcentury rhythm.

The Sound of Anticipation

Before the house lights dimmed, the auditorium swelled with a soundtrack that felt equal parts nostalgia and invitation — the cool pulse of Stan Getz and Charlie Byrd’s “Samba de Uma Nota Só,” the cool grace of John Coltrane and Duke Ellington’s “In a Sentimental Mood,” the cinematic shimmer of Lalo Schifrin’s “Silvia,” and the symphonic warmth of Sibelius’ Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 43: III. Vivacissimo & IV. Finale (Zubin Mehta conducting).

Together, they created an atmosphere of poised wonder — music that lingered somewhere between bossa nova ease and orchestral gravity. It was the perfect overture for what followed: Shakespeare filtered through jazz, rhythm, and rebellion.

As the final notes lingered, the audience settled into a hush that felt conspiratorial — as though everyone, knowingly or not, had been tuned to the same frequency of joy.

The Whimsy Begins

As the lights dimmed, a collective hush fell — and then, like the first fizz of champagne, the show began.

I’d never seen Merry Wives of Windsor live before, and what unfolded over the next hour was nothing short of delightful rebellion. Under the direction of Caitlin Lushington and Tori Lee Scoles, the production became a vivid experiment in joy: Shakespeare reimagined through a queer, feminist, 1960s lens. The text remained, but the tone was new — flirtatious, sharp, and hilariously self-aware.

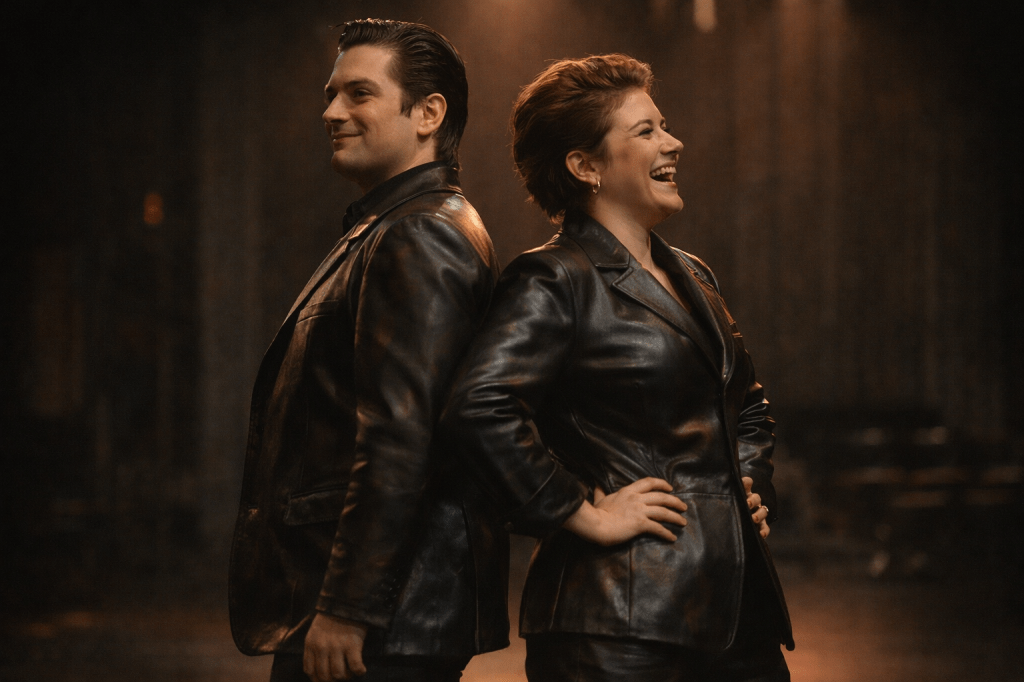

Two Falstaffs — one male, one female — strutted the stage in leather suits, embodying the character’s bombastic ego with mirrored energy. The result was inspired: a doubling that revealed the play’s enduring truth about vanity, desire, and self-deception. Around them spun a world of witty women, gleeful chaos, and perfectly timed innuendo. And the audience — young and old — responded in kind. Laughter rippled through the auditorium, genuine and unrestrained, as if everyone collectively remembered how to be whimsical again.

Editorial Note: I name adult directors and performers in public, professional contexts. Out of respect for privacy, I do not publish the names of student actors.

The Village and the Vision

If the play’s laughter was the body of the experience, its spirit came from the twin philosophies guiding this production: It Takes a Village and Protect Whimsy. Both phrases, taken from the directors’ notes, felt like living mantras rather than slogans — visible not just in how the show was performed, but in how it was made.

Tori Lee Scoles, in her Director’s Notes, wrote of curiosity and community — of how true success in theatre means lifting others as you climb, learning as you fail, and finding joy in collective effort. She connected Merry Wives of Windsor to the early 1960s, an era poised between the polished domestic ideal and the coming cultural upheavals of women’s liberation and civil rights. In her framing, Mistress Page and Mistress Ford were not merely clever wives outwitting Falstaff; they were proto-feminist agents, women who had quietly seized power within the structure of their own society.

The production captured that sense perfectly. Every costume, gesture, and wink to the audience carried echoes of that transitional decade — bright optimism on the surface, subversion just beneath. There were moments that felt like they could have leapt from a Technicolor screwball comedy: women in headscarves and heels outsmarting swaggering men; jazz and bossa nova cues punctuating mischief with cinematic rhythm.

Caitlin Lushington’s companion Director’s Note, Protect Whimsy, offered the counterbalance — a reminder that playfulness itself can be a radical act. She described how her students, in the earliest rehearsals, created company agreements about what they needed to thrive. The phrase “Protect Whimsy” emerged from that conversation — not as an instruction, but as a promise. In her words, it meant choosing joy even amid the pressures of production; preserving curiosity and delight as sacred artistic values.

That ethos radiated from the stage. The cast didn’t perform Shakespeare as an assignment — they inhabited it like a shared secret. You could feel it in the improvisational spark between actors, in their fearlessness with gender-swapped roles, and in their laughter that never felt rehearsed. A male Miss Quickly (played with fabulous comic timing), a female Mr. Page — all of it created a living dialogue between past and present, between what theatre was and what it can still become.

This was not Merry Wives as museum piece. It was Shakespeare filtered through the imagination of a generation that refuses to accept art without joy, or gender without play. And that’s precisely what made it feel alive. They were proto-feminist agents, women who had quietly seized power within the structure of their own society.

The Falstaff Paradox

Few Shakespearean figures have loomed as large — or as foolishly — as Sir John Falstaff. Part jester, part philosopher, part con artist, he thrives on performance itself, spinning charm and deceit in equal measure. In Tigard High School’s production, Falstaff was not one but two performers — a male and a female counterpart — mirroring each other’s vanity like reflections in a warped mirror.

It was a daring directorial choice, and one that paid off spectacularly.

Together, they became the embodiment of Falstaff’s contradictions: desire and delusion, swagger and fragility, masculine ego and human vulnerability. Both strutted across the stage in matching leather suits, their movements half swagger, half self-parody — a little bit Elvis, a little bit Grease, and entirely self-aware. The effect was magnetic. The leather caught the stage lights like a spotlight on ego itself, turning Falstaff’s appetites into aesthetic: indulgence as costume, performance as confession.

The dual portrayal revealed Falstaff not as a single man but as an idea — one that transcends gender and time. Watching them alternate and occasionally overlap felt almost cinematic, like cutting between two sides of the same performance reel. Their antics — scheming to seduce two married women simultaneously — became more than comic folly; they mirrored our own modern absurdities. In an age of dual personas and performative charm, Falstaff feels eerily familiar: the self-styled “main character” forever juggling attention and authenticity.

And yet, by splitting the role, the directors made something rare happen — empathy. For all their bravado, both Falstaffs were achingly human. Beneath the gleam of leather and laughter lay something raw: the yearning to be seen, to matter, to still feel desirable in a world that has quietly moved on. When the inevitable humiliation came, it didn’t land as punishment but as revelation — the audience’s laughter carrying a note of tenderness.

The two actors, both seniors of equal charisma, balanced each other beautifully. Their rhythm made Falstaff’s downfall not just comic but communal — as though the character himself had been cracked open, his flaws refracted through two lenses, both absurd and deeply human.

By the time the fairies mocked and tormented them under moonlight, the doubling no longer felt like a gimmick. It felt inevitable — as if Shakespeare’s own words had found their 21st-century echo in this dual embodiment. A truth discovered not through scholarship, but through instinct, collaboration, and play.

Archival Note: According to the production’s playbill, the student portraying the female Falstaff also serves as Tigard High’s Thespian President, while the student playing Mistress Page is the Thespian Vice President. There’s a poetic symmetry in that — the two student leaders embodying the play’s central tension between mischief and mastery, ego and empathy. It’s as if the spirit of the troupe itself was written into the script: leadership not as hierarchy, but as collaboration in motion.

Whimsy as Rebellion

At first glance, Merry Wives of Windsor seems like one of Shakespeare’s lighter comedies — all flirtation, disguise, and well-timed chaos. But under Tigard High’s direction, whimsy became something more than comic relief. It became defiance.

In a world still learning how to make space for joy without irony, this production’s commitment to laughter felt radical. The humor was unpretentious, the timing sharp, the physicality fearless. There were pelvic gyrations straight out of Grease, pratfalls worthy of a 1960s sitcom, and even a few ad-libs that seemed to surprise the actors themselves. Yet none of it ever slipped into parody. The students were in on the joke — and so were we.

When a male actor as Mistress Quickly quipped or waltzed across the stage in flamboyant fashion, it wasn’t played for mockery. It was confidence through camp — a performance of fluidity that felt genuine, joyous, and entirely owned.

And this was no token casting experiment. Women played the Host of the Garter Inn, Justice Shallow, Simple, Slender, John Rugby (who doubled as a fairy), Baltorf (who doubled as the Fairy Queen), Robert, Robin, Sir Evan Hughes, and Mr. Page. Every one of those performances was grounded, funny, and full of life. Rather than feeling like substitutions, these choices gave the play an immediacy — a sense that gender was less a rule than a lens through which to reinterpret power, play, and personality.

The ensemble built an entire Windsor of women — commanding, comedic, quick-witted, and wonderfully in sync. It was refreshing to see how naturally they embodied roles traditionally reserved for men, their interpretations brimming with humor and human truth.

That moment, in its simplicity, embodied the directors’ guiding ethos. To protect whimsy is to protect the right to joy, play, and authenticity. These students weren’t just performing The Merry Wives of Windsor — they were reclaiming it. Turning what was once dismissed as “fluff” into an act of collective courage.

Between acts, jazz underscored it all — smoky bossa nova rhythms and the soft ache of ballads that could have been Coltrane or Schifrin. The sound became part of the play’s heartbeat — a reminder that art, even when playful, carries rebellion in its rhythm.

Whimsy, it turns out, isn’t an escape from the world.

It’s a way of surviving it.

Costume as Character

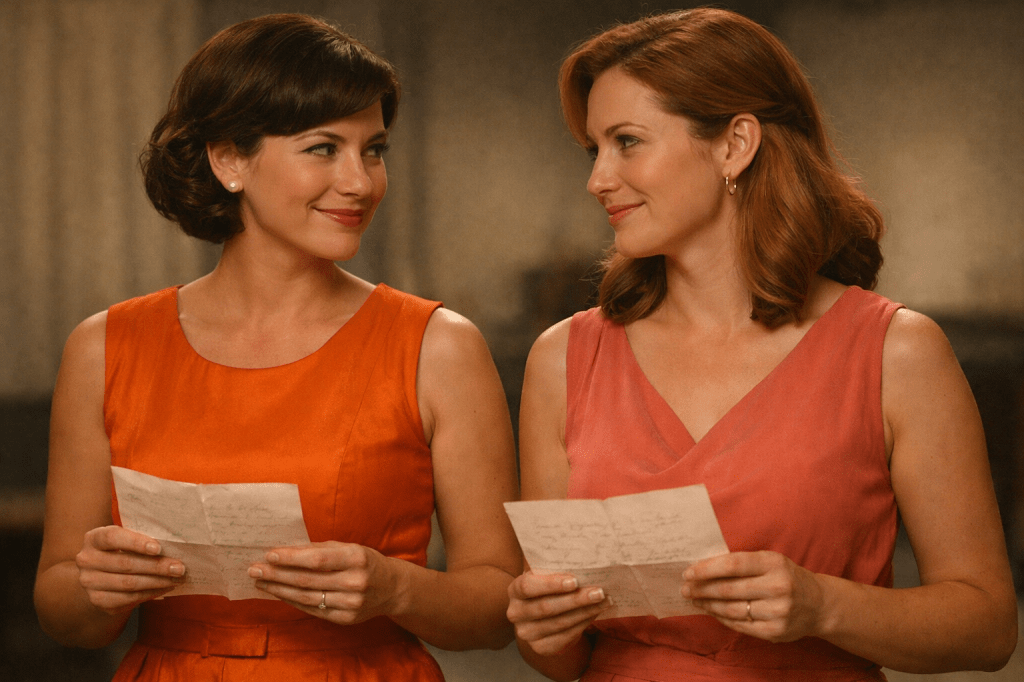

In this Tigard High production, costume design spoke volumes before a word was said. The world of The Merry Wives of Windsor was reimagined through bold 1960s palettes — bright oranges, soft pinks, and seaside pastels — all suggesting a society poised between comfort and upheaval. Nowhere was that more apparent than in the pairing of Ford and Mistress Ford.

Dressed in coordinated orange patterns — his in a loud vacation shirt, hers in a crisp sleeveless dress — the two embodied both harmony and tension. They looked the picture of mid-century perfection, a couple straight out of a magazine spread, yet the coordination hinted at something deeper: the performance of unity masking suspicion and insecurity. Their color palette became an emotional code — sunny on the surface, uneasy underneath.

This was costume as subtext, as storytelling. Each hue reflected the play’s thematic contradictions: playfulness versus power, artifice versus authenticity. Even in the farce, the visual world reminded us that appearances, no matter how cheerful, are never the full truth.

Why This Production Stands Out

What Tigard High’s Merry Wives of Windsor achieved was more than inventive direction; it was cultural clarity. By trusting a young ensemble to reinterpret Shakespeare through humor, queerness, and collaboration, the directors proved that classic theatre doesn’t need opulence to feel alive — it needs courage. Every artistic choice, from the split Falstaffs to the mod-era soundtrack, reflected intention rather than novelty. The production embraced inclusion not as a statement, but as practice, allowing its students to inhabit power, joy, and absurdity without apology. In doing so, Tigard High School Theatre created a Merry Wives for this century: one where gender is playful, community is sacred, and whimsy is a form of resistance.

Epilogue: The Village Applauds

When the final applause rose through the Deb Fennell Auditorium, it felt less like noise and more like recognition — not just for the students on stage, but for the entire village that had lifted them there. Parents, friends, teachers, designers, directors — every hand in that standing ovation belonged to someone who had protected whimsy in their own way.

The dual Falstaffs took their bows together, two seniors closing their high school careers not with restraint, but with riotous laughter and heart. Watching them, I thought of the late Orson Welles — his deep affection for Falstaff as “the greatest part ever written.” He would have been delighted by these two student actors: one male, one female, both swaggering, both self-aware, both achingly human. They made the role their own, balancing Wellesian grandeur with a kind of modern, rebellious vulnerability that belongs wholly to this generation.

Around them, the rest of the cast gathered — an ensemble bound by the same fearless spirit. These students had done something remarkable: they took a centuries-old play and made it feel new without losing its soul. They showed that The Merry Wives of Windsor can be feminist, queer, comedic, and deeply communal all at once.

As the house lights came up, I lingered for a moment before leaving. I didn’t know these kids, yet I felt proud of them — proud of their courage, their humor, their unguarded joy. In a world that often undervalues the arts, they reminded me what it means to create simply because you love to.

Maybe that’s what “protecting whimsy” really means: showing up, even quietly, for the people who still believe in imagination.

Archival Meta Note: I’m not a professional archivist, but I approach these productions with an archivist’s care. These notes are my way of preserving not only what I saw on stage, but why it mattered — as memory, as culture, and as a record of care. In that choice, the archive becomes not just a record of art, but a record of care.

You must be logged in to post a comment.